Russia invaded Ukraine on the day before Independence Day last year, setting off a chain of events that led to Ukraine’s worst military defeat and a humiliating agreement in Minsk, Belarus, that has not brought peace or ended Russia’s war.

Four Russian tactical battalions numbering 2,000 soldiers, and columns of armored vehicles and artillery units invaded southeastern Donetsk Oblast on Aug. 23, 2014. An identical invasion force entered Luhansk Oblast over the holiday, according to a Defense Ministry report published on Aug. 20.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The Russians entered Donetsk Oblast from three directions, based on a map the Defense Ministry provided. Ukraine’s border guards on Aug. 23 reported a big column heading toward Ilovaisk, 25 kilometers east of Russian-occupied Donetsk and 45 kilometers from the Russian border, according to a parliamentary report in October.

The Russian troops did not have insignia or patches and their vehicles were unmarked. Their presence, without declaration of war, marked the biggest intervention by regular Russian troops.

By Aug. 25 they surrounded Ilovaisk, where 1,200-1,400 Ukrainian soldiers were trying to wrest control from Russian-separatist forces as part of what had been a steady advance to liberate cities and towns in the Donbas.

After the massacre of 366 soldiers, according to the official military prosecutor’s death count, Kyiv not only stopped advancing but ended up retreating and losing territory. Some 157 of those slain soldiers remain unidentified.

Summer assault

By mid-August Ukraine had liberated 60 percent of the area that separatists had occupied since mid-April 2014. Kyiv was entering its third month of an offensive to reclaim Donbas when it moved to free Ilovaisk, a key railroad junction with a pre-war population of 16,000 people. Ukrainian forces had sealed off occupied Donbas from three directions: north, south and west. “The militants could only receive weapons and reinforcements from the eastern direction, foremost, from the territory of the Russian Federation,” reads the Defense Ministry report.

Kyiv’s military assessed its strength at 40,000 troops, or rough parity with Russian-separatist forces. The report stated that it didn’t count an additional 4,000 serving in volunteer battalions.

“In this manner in mid-August favorable conditions were created to seal off the militants in areas at Horlivka, Alchevsk, Stakhanov, Luhansk and Donetsk, which allowed us to hope for the completion of the anti-terrorist operation by the middle of September,” the Defense Ministry stated in its report.

Donbas was operationally divided into four military sectors – A, B, C and D – with the coastal city of Mariupol being part of a separate district M.

Ilovaisk was in sector B, supplied only from the east. To separate the occupied regional capitals of Donetsk and Luhansk from each other, Ilovaisk had to be taken. The city stood in the way of the only main supply route through Shakhtarsk via Zuhres along the H21 highway.

But weeks before Ukrainian forces entered Ilovaisk, Russia had already started to prepare for its decisive military intervention in Ukraine.

According to Bellingcat, a British open-source intelligence outfit, cross-border shelling from Russia started in mid-July and lasted through early September. This made it increasingly difficult for Ukraine to hold border areas and prevent the supply of weapons and Russian mercenaries and servicemen from penetrating Ukraine. Incessant shelling originating in Russia exposed Ukraine’s right flank in Donetsk Oblast and allowed the invading Russian force to surround Ilovaisk.

Operation Ilovaisk

Ukraine made three unsuccessful attempts to take Ilovaisk in August 2014.

On Aug. 5, 2014, Kryvbas Battalion was the first to be given orders to take the city by Aug. 7, backed by the 51st Mechanized Brigade.

The unit conducted reconnaissance and discovered “clusters of militants inside Ilovaisk” and “fortified positions” in the city as well as on the outskirts and in nearby villages, according to a combat mission report the unit published after the final battle took place later in August.

“We observed loads of concrete blocks being transported to Ilovaisk, we understood they (separatists) were not constructing new residential buildings but were erecting fortifications… We stopped watermelon trucks that had self-propelled artillery canons and equipment hidden on the flatbeds,” Mykola Kolesnik, administrator of Kryvbas, told the Kyiv Post.

Despite its findings, Kryvbas and the 51st Brigade, equipped with just two tanks and two armored combat assault vehicles, were ordered to take the city.

It conducted four unsuccessful attacks on Aug. 6-7, according to the unit’s report.

Two Kryvbas troops were killed and two of its combat reconnaissance vehicles were destroyed during the missions, according to the unit’s report.

The next assault took place on Aug. 10, with Donbas, Shakhtarsk and Azov tasked with completing the mission. Volodymyr Maksymiv, who was deputy commander of a Donbas reconnaissance platoon, told the Kyiv Post that the Right sector also participated in the offensive.

Azov soldiers were stopped halfway into town, pinned down by sniper fire. Three of its soldiers were killed.

“We were told the city was empty with only about 50 people defending it… We got bad intelligence,” said Stepan Baida, who was aide-de-camp to Azov Battalion commander Andriy Biletsky.

Donbas advanced further, but couldn’t enter it, losing four men, including the battalion’s deputy commander, according to Vyacheslav Vlasenko, who took charge of the battalion after its commander Semen Semenchenko was wounded on Aug. 19.

Shakhtarsk didn’t lose anyone but got pinned down by sniper fire less than two kilometers from the city, Ruslan Onyshchenko, deputy commander of Shakhtarsk, told Hromadske TV.

Ukraine’s military then approved another plan to take Ilovaisk, involving battalion units from Donbas, Dnipro-1, Azov and Shakhtarsk.

Meanwhile, Kryvbas had set up four fortified bases manned by 30-40 men surrounding the city, supported by the 51st Mechanized Brigade, with a tank and a combat assault vehicle stationed at each.

Gen. Ruslan Khomchak, head of sector B, was the operation commander. Apart from the 51st brigade, the 28th Mechanized Brigade and a tactical platoon from the 93rd Mechanized Brigade joined them, giving the assault team a combined force of 940.

On Aug. 16, Khomchak, Deputy Interior Minister Serhiy Yarovy and the four battalion commanders met at Azov’s base in Urzuf near Mariupol to discuss the new Ilovaisk operation, according to parliament’s report.

The assault date was set for Aug. 18.

Ninety minutes after reporting to military headquarters, Khomchak received orders to start the offensive a day earlier, according to the parliamentary report.

Only Donbas arrived on time at 5 a.m. on Aug. 17 at the gathering point at Mnohopillya, with Dnipro-1 arriving several hours late. Azov would arrive the next day while the parliamentary reported stated that Shakhtarsk pulled out of the operation.

Dnipro-1 and Azov first approached the city from the east via Vynohradne, where the fortified positions were, but made little headway. Donbas first took the village of Hrabske southwest of the city on Aug. 17. The next day it entered the city from the west side, which wasn’t fortified, meeting little resistance. They were supported by artillery fire coming from Mnohopillya, 9 kilometers south of Ilovaisk.

Donbas by Aug. 19 had taken half the city, which had a railroad bisecting the middle of it with bridges linking the two sides. Semenchenko was wounded the same day and left Ilovaisk. The following day some units from Dnipro-1 joined Donbas in the western part of the city.

Azov meanwhile faced delays entering the fight. On Aug. 18, its column left Shyrokyne and was hit by Grad rockets from inside Russia near Telmanove. It reached Mnohopillya on Aug. 19 and immediately dispatched a platoon to join Donbas, but for unknown reasons it couldn’t reach them, according to Biletsky’s aide, Baida. The following day, Azov sent three infantry and one reconnaissance platoon towards the eastern part of Ilovaisk.

“We saw highly organized fortified defensive positions,” Baida told the Kyiv Post. “We took mortar fire… (and) our artillery couldn’t get them, but we started clearing the city anyway, meeting fierce resistance along the way, and they were hitting our rear with Grad rockets from Shakhtarsk (further from the east).”

Three Azov soldiers died at or near Ilovaisk on Aug. 20-23, according to Memory Book, a civic group that tracks war casualties with supported from the National Military War Museum. Azov then left the area as a Russian column had also started breaking into the coastal city of Novoazovsk, some 45 kilometers east of Mariupol, which was mostly undefended at the time.

Battalions Myrotvorets, Ivano-Frankivsk, Kherson, and a platoon from Svityaz had also joined Donbas and Dnipro-1 during this time.

The National Security and Defense Council announced on Aug. 20 that Ilovaisk was under the “complete control of Ukrainian security forces,” but the battalions maintain that they never controlled more than half of the city, and that they faced stiff resistance and daily attacks.

It was already difficult to access the city by Aug. 21, Maksymiv of Donbas Battalion told the Kyiv Post. Armed forces in Mnohopillya didn’t want to let his unit go further when he arrived to re-supply his comrades and evacuate the wounded.

A Ukrainian T-64 tank stands charred from a

landmine explosion in the village of Hrabske four kilometers south of

Ilovaisk in Donetsk Oblast on Aug. 17. (Aleksander Glyadyelov)

He went anyway and faced fire at Hrabske, where positions were growing untenable. His unit reached Ilovaisk but they only managed to get two cars with wounded out of the city.

“By Aug. 23, it was impossible to get out of the city,” Maksymiv said, but they still had access to the neighboring village of Zelene to the north.

“There were two-three fights a day, they were hitting us with Uragan rockets,” Kolesnik of Kryvbas said. According to operation plans, Kryvbas was supposed to hold the four security roadblocks around Ilovaisk for two-three days, but held them for 21 days, the unit’s combat mission report stated.

“Direct contact with enemy forces took place daily, with firefights lasting up to seven hours,” according to the report. “The number of rounds fired from BM-21 Grad systems and mortars reached 300 per day.”

Moreover, Russian-separatist forces from Donetsk in the west and Shakhtarsk in the east were reinforcing Ilovaisk or staging attacks on Ukrainian positions near the city.

Russia turns tide of war

When Army General Staff chief Viktor Muzhenko allegedly heard from reporting officer Gen. Petro Lytvyn at 2:30 p.m. on Aug. 23 that Russian forces had invaded Donetsk Oblast, he said: “If the situation changes, report in the prescribed manner.”

The next morning at 10:30 a.m., according to the parliamentary report, Lytvyn’s subordinate, Col. Petro Romyhailo, reported to headquarters in Kyiv that more than 100 Russian armored vehicles, including airborne assault vehicles, tanks, self-propelled artillery units and large numbers of trucks with personnel and ammunition were on a highway that leads to Ilovaisk.

“Fuck off! Cowards! I’ll put you in prison!” Gen. Viktor Nazarov responded, cited by the parliamentary report.

At approximately noon, according to the legislature’s report, Muzhenko received the same information and said: “Don’t be a coward. This is bullshit. We’ve been through this.”

A Kryvbas reconnaissance unit captured 10 Russian airborne troops near Osykove village on Aug. 24, battalion administrator Kolesnik told the Kyiv Post, an event that was widely reported by the Ukrainian media.

“How do you deny an invasion after this?” he said.

Ukraine’s Defense Ministry disputes the chronology of events. Generals in Kyiv only “definitively” confirmed Russia’s invasion on Aug. 26, after it started receiving reports the previous day that the invasion had occurred on Aug. 24, Independence Day, the Defense Ministry’s report stated.

“We never thought that Russia would act so treacherously and bring its troops into Ukraine without a declaration of war,” Army General Staff chief Muzhenko told Novoe Vremya magazine this month. “They kept saying they’re not a party to the conflict.”

By midday on Aug. 24, according to the parliamentary report, Russian forces were hitting the rear of Ukrainian military positions southeast of Ilovaisk. By midnight, Ukraine’s military Sector D – tasked with protecting 140 kilometers of the border with Russia and guarding the right flank – no longer existed, as the military command had liquidated it.

The sector’s remaining 1,000 troops – they had numbered 4,000 on July 23, 2014 – were incorporated into neighboring sector B. The remainder either were captured, killed, wounded, went missing, were re-assigned or had abandoned their positions, according to the Defense Ministry.

Combined with another invasion by four Russian tactical battalions with military hardware in Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine had by this time decisively lost military superiority to the combined Russian-separatist forces, the Defense Ministry stated.

At Ilovaisk, “the balance of Ukraine’s forces to the total number of illegal armed groups and the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation was 1 to 18 in manpower; 1 to 11 in tanks; 1 to 16 in armored vehicles; 1 to 15 in artillery; 1 to 16 in mortars,” chief military prosecutor Anatoliy Matios said in Kyiv on Aug. 14. “Victory for the Ukrainian side in such conditions was impossible.”

Between 1,200 and 1,400 Ukrainian servicemen, according to different official versions, were already encircled at Ilovaisk by Aug. 24.

Exposed right flank

Shelling inside the country and from Russia decimated Ukraine’s forces in sector D, and allowed Russia to invade and join the battle for Ilovaisk with relative ease.

Muzhenko, in the interview with Novoye Vremya, attributed the gradual disintegration of sector D to weak leadership and the inability of certain military units to carry out missions, and their level of psychological toughness.

Some units left assigned positions for safer ones, while others deserted, he alleged.

Equally important, Ukrainian forces could not install artificial obstacles such as mine fields or engineering obstacles because of the disorderly fashion and haste in which they abandoned their positions.

Such incidents left the flank bare, and explain why the Russian column quickly reached Ilovaisk along highway T0507 through Amvrosiyivka and Kuteinykove, according to the Defense Ministry.

Three kill zones

From his hospital bed on Aug. 25-28, Semenchenko of Donbas kept asking for help to relieve the besieged Ukrainian volunteer battalions, or orders for them to leave.

No help came.

Meanwhile, Muzhenko was negotiating with Nikolai Bogdanovsky, first deputy chief of the Army General Staff of the Russian Federation, to secure safe passage out of Ilovaisk for the Ukrainian forces. The Russian officer promised they could leave with their arms and equipment.

Russian President Vladimir Putin early on Aug. 29 had also asked the separatists to create a “green corridor” for the surrounded Ukrainian servicemen.

At 11 p.m. on Aug. 28, Bogdanovsky called Muzhenko back to say that the conditions had changed – weapons and hardware had to be surrendered. Aleksandr Zakharchenko, the self-proclaimed separatist leader in Donetsk, also gave the same condition.

At a lower level, sector B’s military leadership had agreed with their Russian counterparts to leave with their weapons in tow, according to the Defense Ministry report.

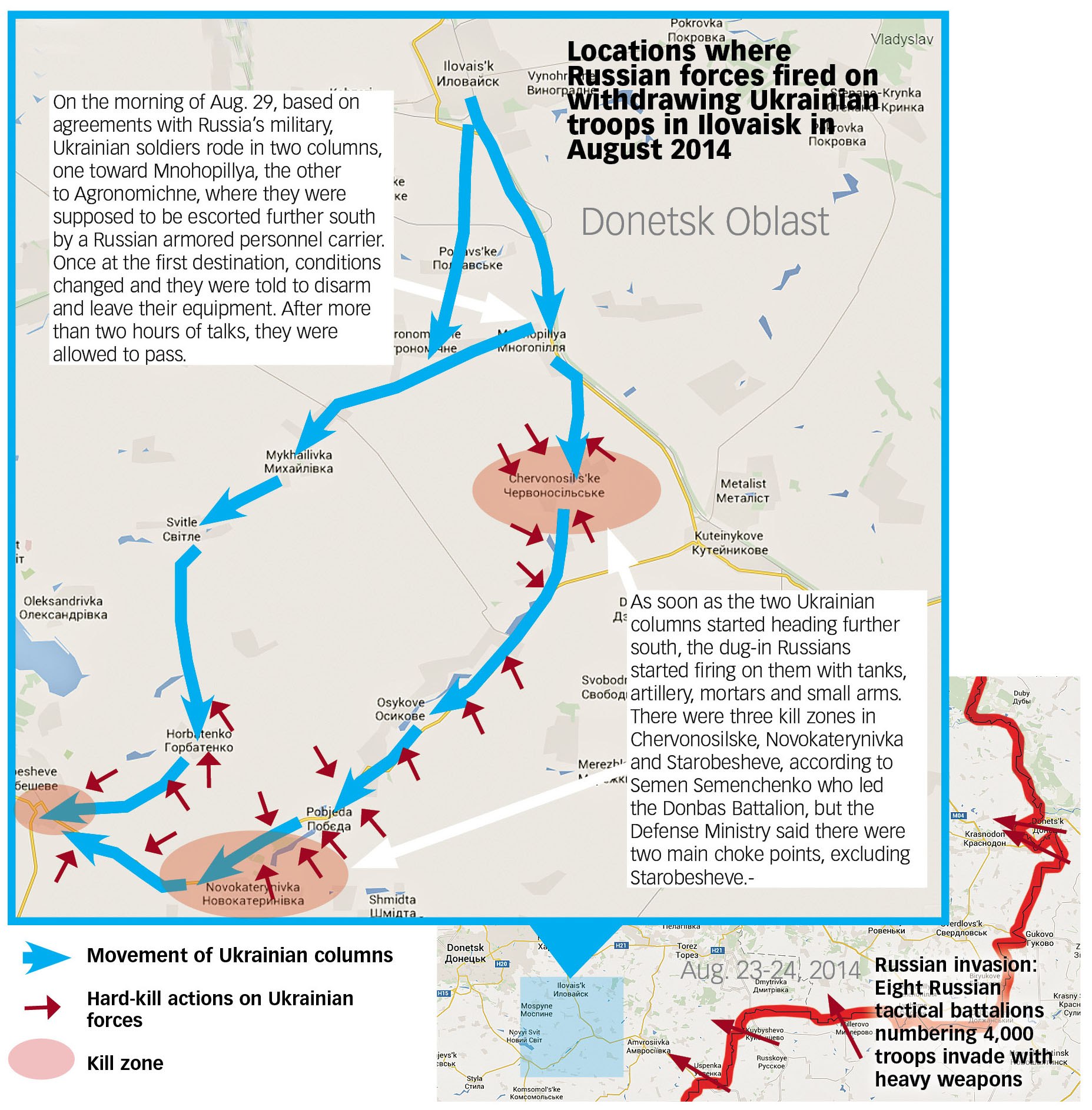

On the morning of Aug. 29, two columns – one heading south toward Mnohopillya, the other southwest toward Agronomichne – were supposed to be met by Russian armored personnel carriers at each destination. The Russian vehicles were to escort the columns to Starobeshevo and Novokaterynivka further southwest.

At 6 a.m. in Mnohopillya, an unnamed Russian officer, according to the Defense Ministry, said the conditions had changed. Weapons and hardware needed to be left behind. At around 8:30 a.m., following more talks, the Russians let the Ukrainians pass without disarming.

The extra time in the morning let the Russians dig in and secure optimal firing positions for their tanks and artillery, according to the Defense Ministry report.

“As soon as we started moving out of Mnohopillya, we started to get hit by mortar fire from the direction of Kuteinykove,” Maksymiv of Donbas, who was in the cab of a truck, told the Kyiv Post. “We took off, but once we got to Chervonosilske the dug-in tanks got us, along with artillery.”

A bullet grazed the right side of Maskymiv’s face, “I first went into shock and then lost consciousness, I thought I was going to die,” he said. “The entire road was on fire, it was straight from the movie ‘Transformers,’” Maksymiv added.

Despite the huge disadvantage, the column fought back. Donbas and other units destroyed three Russian tanks, one self-propelled artillery unit, two combat assault vehicles, and captured four tankmen, one paratrooper, and two anti-tank bazookas.

The other two pre-arranged kill zones were in Novokaterynivka and Starobesheve, where dug-in Russian tanks, artillery units and troops struck the Ukrainian columns, according to Semenchenko.

The rout — which ended with 366 killed, 429 wounded, 128 taken prisoner and 158 missing, according to declassified information released by Ukraine’s military prosecutor’s office on Aug. 5 — became known as the Massacre of Ilovaisk.

A map of the war zone in eastern Ukraine as it looked on Aug. 18, 2014, the day Ukraine’s main assault on the city of Ilovaisk started. By mid-August 2014, Ukraine’s forces had liberated 60 percent of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts that Russian-separatist forces had occupied since mid-April 2014. The red circle shows the territory that Russian forces control today.

Military, political consequences

Judy Dempsey of Carnegie Europe told the Kyiv Post that the battle at Ilovaisk made Russia’s intentions clear.

“Ukraine’s inability to defend itself was absolutely exposed,” she said. “One thing is certain, Russia won’t let Ukraine go even though it is slipping out of its orbit.”

The Ilovaisk catastrophe sent Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko to the first truce talks in Minsk on Sept. 5 with a poor hand. His only trump was the Russian dog tags that were taken from the battlefield, showing undisputed proof of Moscow’s involvement in the war.

All the same, Ukraine got unfavorable peace terms, agreeing to give the Donbas special status. The first Minsk agreement didn’t even mention Crimea, which Russia had invaded and annexed in March 2014, and there were no clear provisions for returning control of the Russian border until the end of 2015.

“Ukraine wasn’t treated as an equal voice,” Dempsey said. “It is quite extraordinary that Crimea was illegally taken over; then the August (Ilovaisk) catastrophe happened… Ukraine wasn’t given full political status for those negotiations… That changed in February when (German Chancellor Angela) Merkel put her weight behind (the second Minsk agreement).”

But in the six months since the Minsk II agreement, Ukraine has only been steadily losing lives and territory, with no end to Russia’s war in sight.

Kyiv Post editor Mark Rachkevych can be reached at rachkevych@kyivpost.com. Kyiv Post editor Euan MacDonald contributed to this report.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter