Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on Coda Story website and is republished with permission.

Why Russian ultranationalists confronted their own government on the battlefields of Ukraine

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

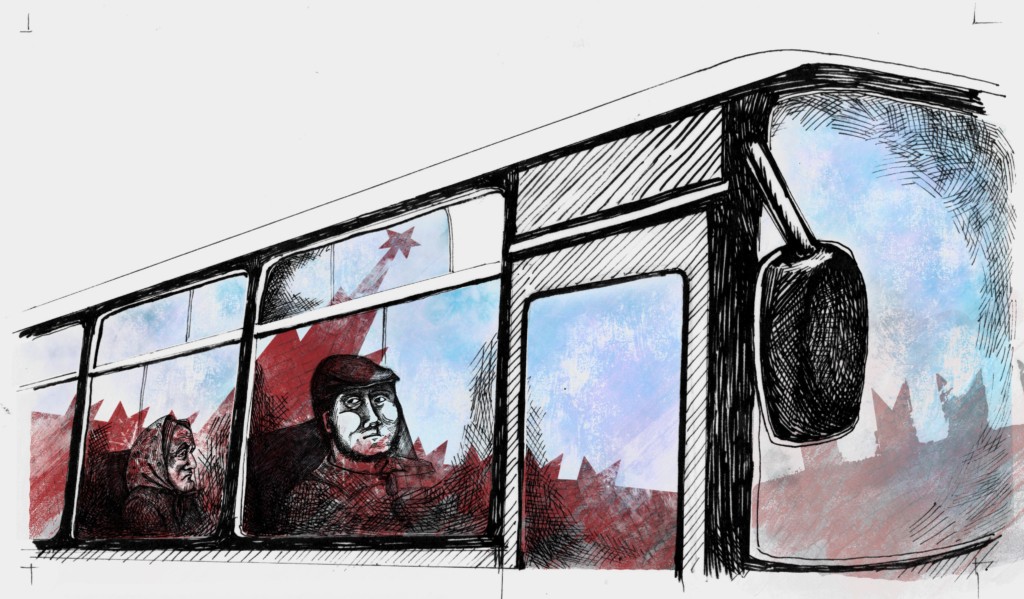

On a snowy January day in 2016, a small crowd assembled in central Kyiv to honor the fight against the far right. The gathering of diehard anti-fascists was commemorating the 2009 murder of the Russian lawyer Stanislav Markelov, who’d defended activists and victims of the Russian military, and the Ukrainian journalist Anastasia Baburova, who’d investigated neo-Nazi gangs.

- See the most contemporary Ukraine news reports for today.

- See the most contemporary Ukraine news reports for today.

- Russian Losses in Ukraine War

As they unfurled banners in memory of the pair, a group of young men confronted them. In footage posted online, the men, many of them masked, identify themselves as members of the Azov Civic Corps, a Ukrainian ultra-nationalist movement linked to a regiment fighting Russian-backed rebels in the east.

An unmasked Azov member, sporting a strap-like beard across his chin, begins arguing with the crowd. Like most people in Kyiv, he speaks in Russian — but his accent is distinctly Muscovite. He refers to the murdered lawyer as one of the “scumbags” responsible for imprisoning his friends. Someone in the crowd responds: “But is it OK to kill people because of their political views?”

“Of course it is OK,” the bearded man says. “If these views contradict the interests of the nation, they should be uprooted.” Although he does not mention any nation in particular, he refers to Russian soldiers as his “blood brothers” and condemns the murdered lawyer Markelov as a “Russophobe.”

The left-wing activists appear puzzled. Their public assemblies had always risked clashes with their homegrown opponents, the Ukrainian ultranationalists. Yet here they were in their capital, Kyiv, amid a war with Russian-backed forces, quarreling with a Russian agitator somehow aligned with the Ukrainian far-right.

Internationalist ultranationalism

The man’s name is Roman Zheleznov, and he is indeed a Russian citizen. He is also an ultranationalist who idolizes the neo-Nazi gang-leader convicted of murdering the lawyer and the journalist. Many of his fellow ultranationalists from Russia have, predictably enough, backed the pro-Russian rebels in their war with Ukraine.

But Zheleznov is part of a Russian contingent that has wound up on the opposite side, joining the Ukrainians fighting against the rebels. Their exact number is hard to confirm, as they keep a low profile. Zheleznov puts it at 200, while others speak of several dozen.

These Russians are, in effect, battling a proxy military force that is sustained by their own government and that includes their former comrades from the far right. But their brand of nationalism cuts across national borders. In this sense, they are paradoxical figures — “internationalist” ultranationalists.

Their journey can be traced to the Russian far right’s complex relationship with their country’s institutions and with similar groups in Ukraine. Most of the Russians who champion the Ukrainian cause began their careers with ultranationalist gangs back home. These gangs had powerful sympathizers and at times enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with officialdom, advancing its aims and battering its opponents. In return, they seemed to receive immunity from prosecution and access to resources.

While individual gangs have periodically supported official causes, the Russian far right as a whole has remained independent of the state. Perhaps inevitably, gangs that have served the authorities have, at other points, run afoul of them. Their involvement in violence and criminality has made them easy targets for prosecution when this relationship goes sour.

During crackdowns at home, many gang members have sought shelter in neighboring countries, including Ukraine. In doing so, they have exploited — and strengthened — existing links between the region’s various far-right groups. These are ties that have typically been forged online and on foreign visits, with like-minded individuals mingling at skinhead concerts, summer camps and soccer matches.

When the war broke out in Ukraine in 2014, Russian ultra-nationalist gangs constituted a powerful and unruly street movement. They enjoyed contacts with a network of similar groups abroad, and while many had served the Russian government’s aims, their collective loyalty to that government could not be taken for granted. Their role in the Ukraine conflict would therefore be far from straightforward.

The war gave a huge boost to President Vladimir Putin’s domestic popularity — and sent fissures through the far right. Many ultranationalists expressed their support for Putin and the pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine. Others supported these separatists but would turn against Putin. Most notable among them was an ultranationalist former security officer, Igor Girkin, known as Strelkov. He had ignited the uprising in eastern Ukraine but swiftly fell out with the Kremlin and has recently called Putin a “prostitute who can’t choose between her American and Chinese client.”

Other ultranationalists, like Zheleznov, would defy Putin as well. They looked to the Ukrainian far right as their true comrades and to Ukraine itself as a platform for challenging the Kremlin.

Since 2014, the Russian authorities have prosecuted hundreds of ultranationalists, suspecting that they sympathize with the Ukrainian enemy. “Nationalists are the best organized opposition group in Russia,” says Aleksandr Verkhovsky, an expert on political extremism at Moscow’s Sova think tank. “So I’m not surprised the authorities are clamping down on them.” He says the latest crackdown has been “harsher than on any other political force in Russia,” except the Islamists of the banned Central Asian Hizb ut-Tahrir group.

Under pressure, Russian ultranationalists have continued taking sides. For those who oppose the Kremlin, Ukraine occupies a place like the one once held by Syria in the jihadist imagination. It represents a test of loyalties, a revolutionary ideal, an escape from troubles at home, and a chance to gain battlefield experience with one’s comrades.

If any of this is a surprise, it is because of the way the war has been reported in both the West and Russia. For many in Europe and the U.S., the conflict in Ukraine has shown Putin to be the very embodiment of Russian nationalism. The president’s actions in Ukraine have indeed boosted his standing among many nationalists at home. He does not, however, have their universal support. This Western understanding of Putin fails to explain how the conflict in Ukraine can pit his opponents, such as Zheleznov and Strelkov, against each other.

Meanwhile, Russia’s propaganda has portrayed the country’s adversaries in Ukraine as neo-Nazis, striving to avenge historic defeat by the Soviet Union. The conflict has emboldened Ukrainian groups with fascist tendencies, catapulting their leaders into military and political roles. Yet they have fared poorly in elections, and depend on oligarchs and mainstream politicians for support. The Russian view, too, is unable to explain how Ukrainian nationalism has ended up attracting Russian ultranationalists, such as Zheleznov.

Both the Russian and Western narratives are incomplete. If figures like Zheleznov appear self-contradictory, it is because they do not fit into either of them.

“A racist”

The Kiev confrontation ended abruptly. The ultranationalists heard a quick speech from their Ukrainian leader, joined him in a chant of “Sieg Heil,” and marched off into the snow. The online footage captures the curious mood of the encounter — the bemusement of the left-wingers and the bravado of their antagonists. At one point, Zheleznov is filmed teasingly pulling an anti-fascist activist’s hat over his eyes. Seconds later, smiling, he cocks his fingers and mimes shooting the activist in the head.

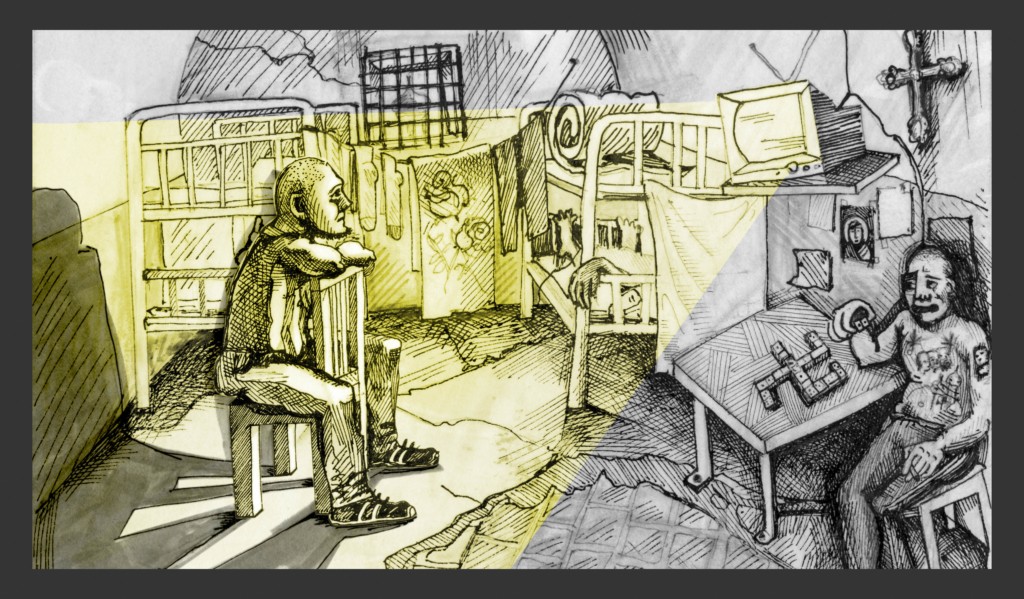

As a teenage neo-Nazi in Moscow, he did it for real. During a routine street fight with anti-fascists, he fired a shotgun at the back of another man’s head, earning his first prison sentence. His victim, struck by rubber pellets at close range, was lucky to have survived. “He’s got a solid skull so he wasn’t even crippled,” Zheleznov recalls with a smile when we meet in Kyiv, three weeks after the filmed encounter with the left-wingers.

Born into Moscow intelligentsia, Zheleznov proved to be a bright student, skipping a grade at secondary school. He took a keen interest in history and classical Russian literature, and says he entered the nationalist subculture through heavy metal and punk music, rather than through the well-trodden route of soccer hooliganism. In 2009, the year he first went to jail, he also graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Moscow’s elite High School of Economics. As he approaches 30, he has a boyish smile and narrow eyes. He pays close attention to his clothes, revealing a penchant for tweed caps and Harrington jackets, popularized by British mods and skinheads.

Asked to spell out his politics, Zheleznov says that he is, “first and foremost, a racist.” But he adds that out of all political systems, he prefers democracy. Confused, I ask him what he thinks of Adolf Hitler, whom he has praised in online posts. “Hitler was a great man, and I would be proud if I could at least partly follow in his historic path,” he says.

Zheleznov’s updates on the Russian VKontakte social network include quotes from Mein Kampf and references to National Socialism. One post is laced with dark sarcasm about Babi Yar, a prominent Holocaust site in Kiev that is being revamped by Jewish groups following years of neglect. The occupying Nazi army massacred some 34,000 Ukrainian Jews at the woodland location over the course of two days in 1941. During the entire occupation, some 100,000 people would be killed at Babi Yar, including Jews, Roma Gypsies, and Soviet soldiers. “If not for World War II and the German occupation of Kyiv, Jewish organizations would never have gentrified the park,” Zheleznov writes. “Which is another way of saying: Thank you to everyone involved.”

From Russia with Azov

Our meeting place is a quiet café near Kyiv’s Independence Square, better known as the Maidan, the scene of the 2014 protests against President Viktor Yanukovych that precipitated the conflict with Russia. The protests were triggered by the president’s decision to abandon an agreement with the EU in favor of closer ties to Russia.

When the unrest broke out, Zheleznov was serving a second term in a Russian jail, this one for shoplifting. By the time he was released, the protests had become a revolution. He tried to enter Ukraine, succeeding on his second attempt after receiving the support of powerful figures that were assembling a volunteer force to defend the eastern port city of Mariupol from the Russian-backed rebels. The force was named the Azov Battalion, after the nearby Sea of Azov, and it would soon grow to the size of a regiment.

The Azov Battalion was cobbled together in desperation to step in for Ukrainian military units that had been wrong-footed by the rebels. Its core members were known to the authorities for their capacity for violence. They were plucked from a thriving ultranationalist milieu, comprised of gangs of soccer hooligans, or ultras, as well as a large far-right organization, Patriot of Ukraine.

Along with Right Sector, another volunteer force run by Ukrainian ultranationalists, the Azov Battalion would become a magnet for fighters from neighboring countries. Best known among those was the regiment’s head of reconnaissance, Sergey Korotkikh, nicknamed Malyuta after a murderous henchman of Ivan the Terrible. In his native Belarus, Korotkikh had been a member of Russian National Unity, an organization that sought to restore the Russian empire to its old borders. He would later move to Moscow and launch a neo-Nazi organization there, only to flee in 2007 after being implicated in a bombing near the Kremlin. No one was hurt in the attack.

Korotkikh was granted citizenship by the Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, in December 2014. The televised ceremony caused some embarrassment to the Ukrainian authorities, who appeared unaware of their newest citizen’s colorful past.

“When you are defending your country, you welcome everyone who can help,” says Olexiy Kovzhun, a PR consultant who has been steering Azov toward the mainstream. “The last thing you’d ask is whether they have good relations with their families, whether they love their mothers and treat their pets well.” He wears a Star of David prominently around his neck, a mark of his Jewish identity that also serves as a symbolic riposte to the claims of intolerance and anti-Semitism swirling around the Azov regiment.

Kovzhun says the Russians on the Ukrainian side were also valued for the role they could play in the information war between the two countries. “We needed to create an alternative perspective for the Russian audience,” he says. “We needed a few Russian pairs of eyes on our side.”

Over time, the Azov regiment’s battle-field victories, backed by a slick PR operation, have attracted a cult following beyond its far-right base. Its ranks today include fighters from all over Ukraine as well as the U.S., Western Europe, and the former Soviet Union, not all of whom necessarily share the ultranationalists’ convictions.

Racial nationalism

Zheleznov presents his journey to the Ukrainian side as a rebellion against the Kremlin. He describes the nationalism of his Ukrainian comrades as a model for Russia because it’s ideologically purer.

Zheleznov’s views are echoed by other ultranationalists who have sided with Ukraine. They oppose the migration from Central Asia that has propped up the Russian economy with cheap labor. They dispute the nationalist credentials of a Putin administration that has encouraged that migration. And they view Ukraine as a lever for changing the administration.

Verkhovsky, the expert on extremism, says Putin is a nationalist in the imperial sense — he invokes an idealized Russian past. However, he says, many on the far right are nationalists in the racial sense — they invoke an idealized Russian ethnicity. Where Putin views Ukraine as part of Russia’s historic domain, many ultranationalists regard Russians and Ukrainians as ethnic kin — especially compared to migrants from the Caucasus and Central Asia. “Blood means more to them than empire,” Verkhovsky says.

Zheleznov’s past shines a light on the ultranationalists’ murky dealings with the Russian authorities and their links to Ukraine. His contact list is a who’s who of the far right in Russia, including many individuals who are currently incarcerated.

While still in his teens, Zheleznov began compiling a database of anti-fascist activists, hoping this would make it easier to ambush them where they lived. He says this database attracted the interest of the aides to a pro-Kremlin legislator, and he eventually gave them some of the information he had collected.

According to Zheleznov, his contact with the aides had been brokered by Ilya Goryachev, the co-founder of Born, a notorious Moscow ultranationalist gang. Goryachev was believed to have friends in high places. In media interviews, he claimed he was trying to build a broad nationalist movement curated by the government. Born’s political wing, Russky Obraz, staged joint actions with pro-Kremlin youth groups, helping to marginalize and suppress the liberal opposition. At subsequent trials involving Born members, witnesses and suspects said Goryachev had been in frequent contact with senior figures in the Russian parliament, the presidential administration, and pro-Kremlin movements. These statements correspond with other accounts of official dealings with the far right, in which employees and associates of the Kremlin seem to act with autonomy, providing their bosses with a degree of deniability.

The gang’s name — thought to have been inspired by the Matt Damon character in the Bourne spy films — is an acronym for Combat Organization of Russian Nationalists. The gang was co-founded by Nikita Tikhonov, who would eventually be convicted of the murders of the lawyer, Markelov, and the journalist, Baburova. The gang was also responsible for killing anti-fascist activists, foreign migrants, a federal judge, and a boxing champion from the North Caucasus. They beheaded one of their victims, a Tajik laborer, and sent the photos to news organizations, hoping to sow fear among Central Asian migrants. Both Goryachev and Tikhonov have been jailed for life in Russia, while other members of the gang are serving long prison sentences.

The trial of the Born members also revealed their links with Ukraine. Tikhonov turned out to have been living there to avoid murder charges in Russia, before returning to kill Markelov and Baburova. The two gang members accused of beheading the Tajik migrant also fled to Ukraine.

Zheleznov emerged from his first prison term after two years, a rising star of the far right. He was recruited by perhaps the most prominent Russian neo-Nazi of the time, Maksim Martsinkevich. Also known by his nickname, Tesak, meaning “The Hatchet,” Martsinkevich was as much a showman as a militant. He was even featured on Russian TV shows and on the British documentary series, Ross Kemp on Gangs. He appointed Zheleznov as PR man for his new organization, Restruct, which became known for harassing people whom it claimed were pedophiles — though most of them, Zheleznov now admits, were just “regular gays.”

In a typical operation, Restruct would use teenage recruits, posing online as male prostitutes, to lure its victims. Once a meeting had been arranged, Restruct members would arrive at the scene and subject the victim to a prolonged and humiliating ordeal, bordering on torture.

The attacks were filmed and uploaded to sites such as YouTube. One episode features Martsinkevich using a stun gun to threaten a naked man seated in a bathtub. His victim is forced to drink from a bottle containing what appears to be urine, before being ordered to empty its contents onto his own head. Restruct carried out a similar campaign against alleged drug dealers.

Although these attacks were clearly illegal and widely publicized, they did not invite immediate prosecution. They were instead believed to enjoy the tacit support of the authorities, coinciding as they did with the rightward swing in the Russian administration.

Thus Martsinkevich appeared on government-controlled TV stations as an expert on pedophilia, and was interviewed by presenters who seemed supportive of his views. For his part, Martsinkevich helped reinforce the government’s propaganda against its critics by linking them to the alleged pedophiles. In the bathtub episode, he forced his victim to greet the leaders of Russia’s liberal opposition by name.

The law eventually caught up with Restruct in one of the periodic crackdowns on the far right. Martsinkevich fled to Cuba but was extradited to Russia in January 2014 and sentenced to five years for the “pedophile” attacks.

By this point, Zheleznov had fallen out with Restruct over tactical issues. In May 2013, he was arrested and jailed once again, this time for stealing a piece of beef from a supermarket. He claimed he was framed by the police, but Restruct was known to advocate shoplifting as a sideline to the homophobic attacks that formed its core mission.

What next?

For both parties in the Ukraine conflict, the ultranationalists have played a dual role, serving in the trenches and starring in the propaganda. They have been portrayed as valiant patriots and as murderous fanatics, depending on which side they were facing. Yet some of this propaganda has also spun out of control, inadvertently undermining its original purpose.

In early 2014, the Kremlin exaggerated the role of Ukrainian neo-Nazis in the Maidan protests, hoping to discredit the uprising. The reports helped polarize the Russian far right by casting the looming conflict as a turf war between ultranationalists. As the war got underway, some of the Russians joined the Right Sector and Azov, hoping to confront their own government. Others joined the rebels, hoping to defend it.

Both groups pose problems for their masters. The Russian neo-Nazis fighting alongside the rebels have undercut Russian propaganda that sought to identify the Ukrainians exclusively with the neo-Nazis.

The Azov Battalion has also tried to play down its early reputation as an international brigade for ultranationalists. While that image attracted recruits, it also brought scrutiny from Ukraine’s allies. In 2014, after a series of critical reports in the international press, the U.S. Congress explicitly banned Azov from acquiring any of the funds it had allocated for the Ukrainian military. The ban would be quietly lifted a year later as the regiment was incorporated into the Ukrainian military and its ultranationalist leaders began to be replaced by regular officers.

While the Azov regiment retains its original logo and many of its original personnel, its ultranationalist commanders have shed their uniforms to enter the upper echelons of politics and administration. Its founder, Andriy Biletsky, has resigned to become a member of parliament. His former deputy, Vadim Troyan, has become the head of the Ukrainian police. The Azov Civic Corps — whose members confronted the anti-fascist gathering in Kiev last January — has become a political party, calling for Ukraine to develop its own nuclear weapons and replace prison terms with hard labor or capital punishment. The party, led by Biletsky, also wants Ukraine to reject the EU in favor of a regional union with Belarus and the Baltic States.

The far right’s entry into national politics has divided Ukrainian liberals. Can institutions rein in the extremists even as they use these groups as a check against other dangerous forces? Or is this part of a normalization process, whereby extremist views become mainstream?

Many Ukrainians who would not describe themselves as ultranationalist have accepted that ultra-nationalist language and imagery have a place in public life, at least during a time of war. Online, some have adopted these signs and slogans simply as way of defying and trolling Russians.

The Russian authorities, too, may eventually have to reckon with the forces unleashed by the war in Ukraine. Ultranationalists on both sides have come to view the conflict as a landmark on the road to ultimate power.

In a recent VKontakte exchange on the subject of tactics, a seasoned neo-Nazi, under the alias Walter Weiss, summed up the far right’s long game in both Ukraine and Russia.

“Climb the social ladder, pull up people with similar convictions,” he advised. “If you demonstrate results…you can obtain supplies and support from above, which means you have an opportunity to change the system from within.”

This article was produced in partnership with MeydanTV.

Source

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter