The settlement of just two dozen houses quickly grew, and was officially incorporated into the city in 1820. At that point the quiet life of Moldavanka came to an end, and the colony was taken over by entrepreneurs and speculators.

Contrary to expectations, inhabitants claim the district’s name is not tied to Moldova, though some historians point to an old Moldovan colony, located nearby, as the likely source. At present, the area is home to Ukrainians, Bulgarians, Moldovans, Serbs, Jews, Gagauz, Armenians, Russians and Greeks.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

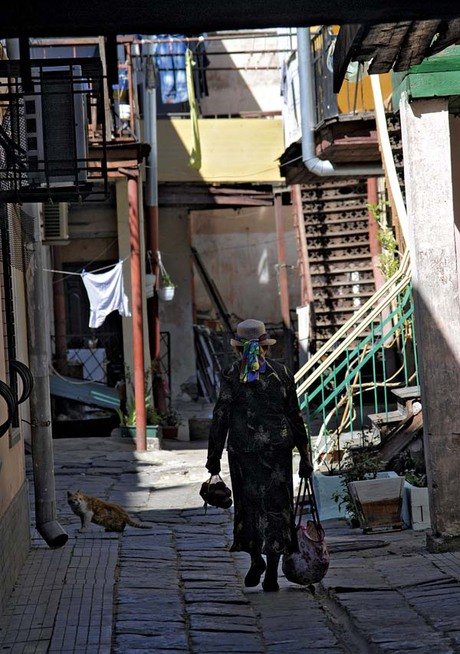

In the late 19th century the neighborhood became congested. Houses were built chock-a-block, with second floors and basements. City authorities put great efforts into controlling the chaotic sprawl, but the maze-like courtyards reflect the intensity of those boom times.

It was in these courtyards that Moldovanka’s social life flourished. Residents used courtyards to cook jam, bathe their children, clean fish and other “dirty” jobs that no self-respecting Odesa woman would perform in her own kitchen. On sultry summer nights locals slept in the yards under acacia tree branches.

Along with their fish and laundry, people brought to the yard their pains, joys, troubles and hopes. It was a place to celebrate weddings and pray for the dead.

It was also a place to treat strangers to a meal, a tradition that lives on to this day. It doesn’t matter whether someone is Russian, Greek, Ukrainian or Turkish – as long as they’re a decent person. It is said that in Moldavanka courtyards, people did not speak Russian, Ukrainian or Yiddish, but their own “Odesa language,” just as people from Paris speak “Parisian.”

Of course, Moldavanka society had its rules, too. It was unacceptable to stick your nose into someone else’s business and, god forbid, be interested in somebody’s earnings. Cursing at food and booze was a taboo, and it was considered shameful to drink with funeral home workers, who were said to be “eating from the table of another’s grief.” One didn’t sit to a meal without having fed and watered the horses first. Those who easily came to blows were disrespected. And one should never be as rude as to leave a company of friends who got together to sit in a pub and to dance to a traditional Jewish “Seven-Forty” melody.

Moldavanka is often mentioned in fictional pieces with settings in Odesa. One of the most remarkable pieces featuring classic old Odesa is Isaak Babel’s “The Odessa Tales.” In the book Babel writes about a gang of robbers who lived in Moldavanka at the beginning of the 20th century. The gang was headed by Benya Krik, also known as The King. The real-life legendary Odesa robber Mishka Yaponchik is said to be the prototype for the main character of the book.

Another interesting Odesa-related fictional character is Ostap Bender, the main protagonist of Ilya Ilf and Yevgeni Petrov’s beloved classics. Ostap Bender, also known as “the Grand Schemer,” dangles throughout Odesa in search of easy money, and is constantly getting into adventures and sticky situations.

“It’s hard to speak about Odesa in general,” as the famous song “Barges Full Of Mullet” goes, but if you want to discover this outstanding city and touch its history, walk the old streets of Moldavanka, explore its courtyards and talk to its inhabitants. That’s where the heart of Odesa beats, hot and passionate.

How to get there: An overnight train leaves from Kyiv to Odesa each day at 21:54, arriving at 6:55. It costs Hr 192 one-way (sleeper car).

Where to stay: Daily apartment rental start at Hr 100, but for reasonable standards expect twice that price.

Eating out: A full breakfast in Kompot restaurant (20 Deribasovska St.) costs Hr 45. Cafes and restaurants in the center will charge Hr 50-100 for a meal.

Kyiv Post staff writer Anastasia Vlasova can be reached at vlasova@kyivpost.com.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter