Not everyone in Kyiv would dare to take a dip in the city’s Dnipro River, but because of the novel coronavirus pandemic, its sun-soaked beaches are the safest places to relax by the water this year.

Kyiv authorities allowed swimming pools to reopen on June 24, but mainly only for individual swim training. Meanwhile, the Dnipro’s beaches have been full of people since the start of June, over two weeks before the city authorities officially allowed swimming there.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

While health experts say that running water and direct sunlight make beaches safer, there are still other dangers in the water: bacteria, pollution and debris. That’s why local authorities in each city, district or oblast inspect the beaches before the swimming season starts.

This year, the results have been unusually late because of the weather and the pandemic.

Despite that, experts say you can still enjoy a swim in a lake, river or ocean in Ukraine will staying safe during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Beaches & COVID‑19

Chief sanitary doctor Viktor Lyashko approved the opening of sea beaches in mid-May. Ukrainian scientists confirmed, he said, that the sun’s ultraviolet rays combined with saltwater kill SARS-CoV‑2, the virus that causes COVID‑19. The virus may live in freshwater, but chances of getting infected are slim in running water, he says.

The U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found no evidence that the virus spreads easily through lakes, rivers and seas, but the issue is still underexplored. Former Ukrainian Health Minister Ulana Suprun says that other coronaviruses rapidly die off in the water, while SARS-CoV‑2 mostly spreads through inhalation of its air particles.

That’s precisely why it is vital to physically distance from other people at the beaches, wash hands frequently and not touch other people’s things. The Health Ministry recommends keeping at least 1.5 meters of distance from other people. Suprun recommends avoiding large crowds near the water. She also says outdoor beaches are safer than indoor pools.

Water inspection

But before going to the beach, it is important to check the local authorities’ website with information about the quality of the water there.

Inspection teams in some regions had trouble conducting the tests because of the COVID‑19 quarantine that Ukraine imposed in mid-March.

Still, the main reason why the swimming season started late this year was the weather. The temperature started rising above 20 °C only in June.

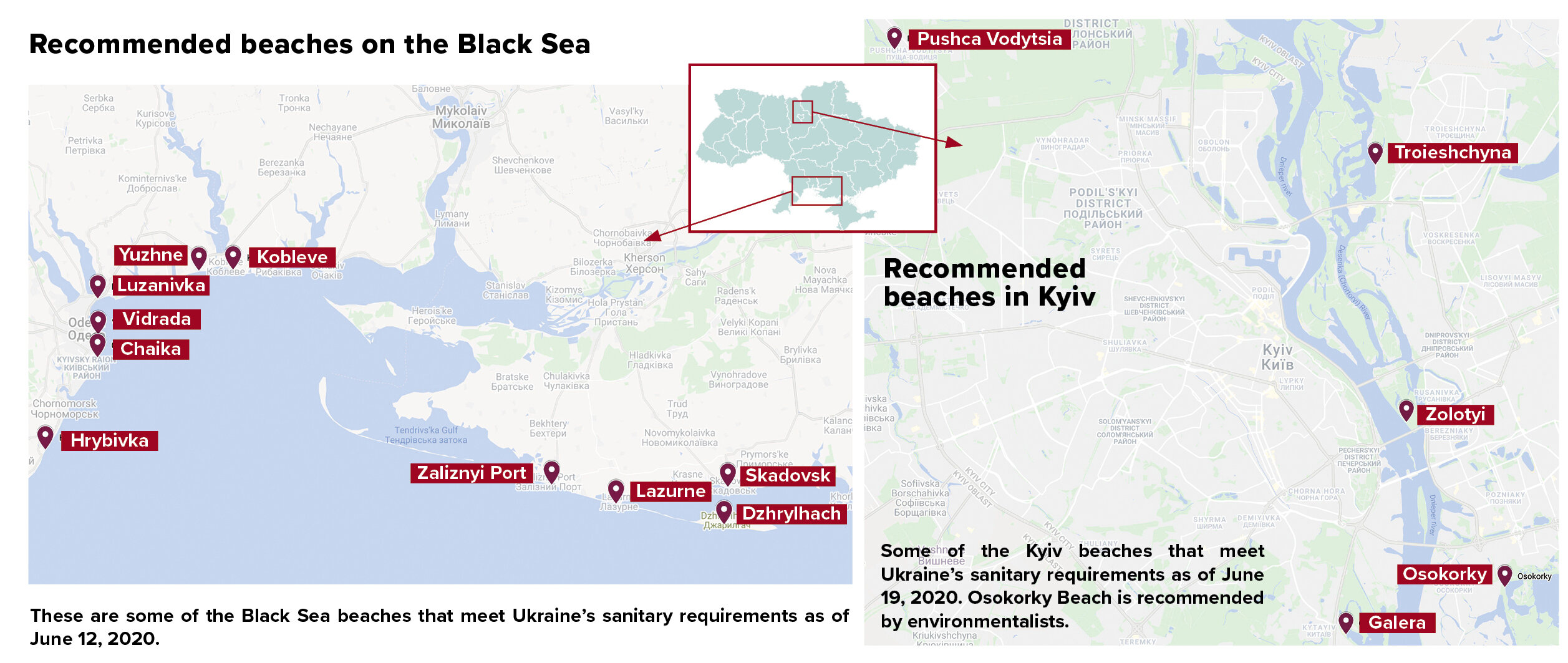

Kyiv officially opened the swimming season on June 19, almost two weeks later than last year, with 14 recommended beaches. As of June 12, the Health Ministry also recommends 70 other freshwater beaches in Ukraine, 22 on the Black Sea and 26 on the Sea of Azov.

Reliability of tests

The tests that local authorities conduct follow state protocols. The water quality is tested using bacteriological and chemical analyzes and should meet a long list of sanitary requirements that Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union. Key points are the oxygen content, the absence of E. coli bacteria and pathogenic contamination.

In Kyiv, beaches are inspected by the Pleso municipal company, which also maintains them. Konstiantyn Pigulia, its director for the maintenance and development of recreational zones, says that their tests are reliable. The only deficiency he sees is that there is no unified state system with relevant information on the quality of bodies of water and beaches, like an interactive map.

“If there was one state system where a person could see the quality of water today in Kyiv, Dnipro, Odesa or other cities — it would be much more convenient, better and faster,” Pigulia told the Kyiv Post.

The State Agency of Water Resources has an interactive map of only the largest bodies of water, but it’s rarely updated and doesn’t include information on where it’s safe to swim. So the best advice is to check the local authorities’ website.

Most local authorities test the water at the beaches only once a year at the start of the season, ecologist Maksym Soroka says, which is not enough. In Kyiv, Pleso tests the water at the beaches every week until Sept. 15 and updates their status on the company’s website, according to Pigulia.

Algal bloom

Updating this information is especially important during the algal bloom season, when seaweed and some bacteria rapidly multiply on the water surface, blocking sunlight and oxygen. This happens when water stays over 25 °C for more than two weeks, Pigulya says. Besides being toxic, such water is simply unpleasant to swim in.

Algal bloom traditionally happened at the end of the summer in Ukraine, but this has shifted toward the beginning of August in recent years.

“Because this year has been quite arid, the concentration of pollution is higher. Sooner or later, it’s carried into the seas, accumulates there and leads to an algal bloom,” says Anna Danyliak, a sustainable agriculture expert.

Like many other Kyivans, Danyliak has avoided swimming in the Dnipro River for many years.

Pigulya says he swims in the Dnipro and recommends eight beaches in Kyiv that have received the international Blue Flag ecological certificate. His favorites are the municipal beach in the Pushcha Voditsa suburb, and the Troyeshchyna beach upriver from all other Kyiv beaches. Soroka said that he is planning a vacation on the Black Sea in southern Ukraine.

“There is really a large number of clean, high-quality bodies of water in each oblast. The problem is that you need to search for them,” he says. “This information should be publicly available.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter