“O brown-eyed maidens, fall in love / But not with Muscovites.”

These first lines from Taras Shevchenko’s narrative poem “Kateryna” in Ukrainian hung over Anna Kopylova’s desk since she was 13.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

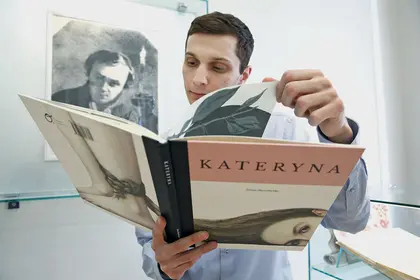

Kopylova, now 31, is the art director of Osnovy publishing house, which has just released the Romantic classic “Kateryna” in English, with illustrations by the up-and-coming artist Nikolay Tolmachev.

“Nikolay created bold, sensual and explicit illustrations,” Kopylova says. “And we chose to publish ‘Kateryna’ because it’s relevant to the recent geopolitical events.”

“Kateryna” tells a story of an eponymous maiden whose love is betrayed by a Muscovite or Moskal – a name also used, often scornfully, for Russian soldiers or Russians generally. This betrayal is reminiscent of Russia’s treacherous war against Ukraine in the Donbas and occupation of Crimea.

Tolmachev’s striking illustrations touch on the issue, but mostly they reflect on Kateryna’s feelings and highlight the severity with which she is punished for her tragic love by her own people.

Years of war

Shevchenko is a national poet of Ukraine, like Goethe is to Germany or Burns is to Scotland. Most Ukrainians remember him from classrooms as a serious old man with a walrus mustache and a fur hat.

Shevchenko’s works have been canonized around this image. And yet “Kateryna” was his first major poem, written in 1838 when he was just 24, a young beardless man studying at the St. Petersburg Art Academy.

A tale of a woman, seduced and then abandoned by a man of higher standing, was not new to Romantic literature. But Shevchenko brought up some new themes, which he kept exploring in his work.

They revolve around the relations between imperial Russia and what was its subordinate, Ukraine. In “Kateryna,” the privileged man represents the imperial culture that abuses the woman, representing a subordinate culture.

Although Shevchenko never says so explicitly, literary critic Roman Veretelnyk says that the poet was aware of the Russian war against everything Ukrainian, and was fighting back.

“When Shevchenko was writing ‘Kateryna,’ he was aware of this war on many fronts, cultural too,” Veretelnyk says. “It goes on for hundreds of years … For modern readers, this (the poem) should be another warning bell.”

Through sensuality and symbolism, Tolmachev evokes this layer of meaning. In one illustration, a popsicle in the form of two-headed rooster (a play around Russia’s coat of arms) is glued to Kateryna’s hair; in another, the rooster is put in front of her loins.

‘Covered woman’

Tolmachev studied at the National School of Fine Arts in France, but then returned to Kyiv, where he now lives and works. He started working on illustrations for “Kateryna” at the age of 24, the same age Shevchenko was when he wrote the poem.

Tolmachev created 20 illustrations in watercolor, his preferred method. His drawings are delicate but sharp, masterfully drawn and colored. But the strongest aspects of Tolmachev’s work are its subtle symbolism and evocative images.

On the front cover of the book, Kateryna lies on the floor looking at the reader with eyes red from crying and her hair extending out of the margins. On the back cover the reader sees that her hair is tied to the Muscovite’s ankle.

Many of Tolmachev’s images are not erotic per se but are suggestive of the sexual. Shevchenko also never explicitly talks about the act, but it’s clearly implied.

“’Kateryna’ is full of eroticism. The plot begins with eroticism and sex – Kateryna’s and Moskal’s rendezvous in the orchard,” Tolmachev says.

Moscal goes off to war after these meetings, promising to come back, but never does. In six months people in the village find out that Kateryna is pregnant and she is cast out as “pokrytka” – a “covered woman” who was defiled and had a child out of wedlock. Even her parents turn their backs on Kateryna.

“This is what got to me the most in this poem: how Kateryna’s parents and her fellow villagers treat her, the women’s status at that time,” Tolmachev says.

According to tradition, a pokrytka’s braids are cut and her head is covered with a kerchief. In Tolmachev illustration, society’s hands cover Kateryna’s whole face and seem to strangle her with the ends of the kerchief.

Kateryna tries to pursue simply what she desires in a very feministic manner, says literary critic Veretelnyk. But for that, she is being used and punished in a patriarchal society.

“She wants to love and pursue her natural needs. But as a result, she becomes a victim of social and political games. Society rejects her … and there are no institutions to defend her,” Veretelnyk says.

The only voice that comes to Kateryna’s defense is the author’s: “What harm to people has she done? / What do the people want? / That she should suffer!”

Orphaned boy

Shevchenko’s “Kateryna” is rather short, only four times larger than this story, and can be read in about 20 minutes. Osnovy’s edition places it onto 40 pages with illustrations taking half of the space. This makes it rather an art book, which was the publisher’s intention.

Osnovy used the revised mid-20th-century translation by John Weir, a Canadian journalist of Ukrainian descent. It’s one of several English translations of “Kateryna.”

“We like this translation the most because the text rhymes well. Shevchenko has this melodious song-like quality … And this translation transmits this sound flow very well,” says Dana Pavlychko, director of Osnovy.

Roman Veretelnyk says it’s too bad that there are no modern translations of “Kateryna.” The new generations could rethink the story, he says, just like Tolmachev did with his illustrations.

“Even if Weir’s translation was perfect, this doesn’t mean there should not be new interpretations,” Veretelnyk says. “The fact that we have to refer to a translation that is over 60 years old indicates the unsatisfactory state of the trade, for Ukrainian classics in particular.”

Kateryna’s story doesn’t get happier. With her newborn son Ivan, she goes off to search for the Muscovite, finds him, but gets rejected by him as well. She drowns herself in an icy pond, leaving an orphaned son, who becomes a guide to kobzar, a blind traveling bard.

The figure of an orphaned son, born of a Ukrainian maiden and a Russian officer, is the only hope that Shevchenko offers. The boy makes the reader look into the future.

“What will this boy do? … Will he avenge his mother? Or, perhaps, help resolve the social tragedies that his mother faced?” Veretelnyk asks.

The reader, of course, is the one who gets to decide.

Buy “Kateryna” for Hr 600 at www.osnovypublishing.com/en/kateryna.

The original Nikolay Tolmachev’s illustrations to “Kateryna” can be purchased at The Naked Room gallery (21 Reitarska St.)

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter