At a bookshop in Kyiv, 33-year-old Yulia Sydorenko was dumping an entire collection of old books — some gifts from childhood friends — that have recently lost their appeal.

Why? They were written in Russian.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

“Since February 24, Russian books have no place in my house,” Sydorenko said, referring to the day Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine.

“I got them for my 20th birthday with inscriptions from my friends. I took pictures of them,” she said of the books she once treasured.

Showing a collection of children’s books, she said she was convinced her children “will never read Russian tales now”.

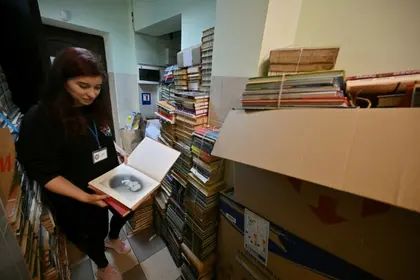

Sydorenko is among a steady stream of people hauling piles of books, sometimes by the suitcase or carload, to the Siayvo bookshop.

Inspired by customers who wanted to clear out unwanted sections of their home libraries, the bookstore decided to recycle Russian-language books, giving the paper a new lease of life and helping the army.

“In two months, we collected 25 tons of books. Their recycling brought in 100,000 hryvnias (2,700 euros),” Iryna Sazonova, the shop’s owner, told AFP.

Following the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the Donbas war in 2014, Ukraine embarked on dismantling Soviet-era monuments and changing place names.

But since February, Ukrainians are contemplating the presence of Russian in private and public spaces, even though 19 percent of Ukrainians say their native language is Russian.

Drone Wars –Technology, Tactics, Strategy, Countermeasures, Legislation

– ‘Nuances are essential’ –

The Bulgakov Museum, where famed Kyiv-born Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov lived for 13 years, has come under pressure, with the National Writers’ Union of Ukraine moving to close it down.

Bulgakov is accused of being imperialist and anti-Ukrainian, notably in his novel “The White Guard” which is at the heart of the museum’s main exhibition.

“War is black and white, but in art, nuances are essential,” the museum’s director Lyudmila Gubianuri told AFP.

“There are many nuances with Bulgakov’s works, but people tend to ignore them,” she said.

Gubianuri accepts that the museum must adapt to reflect the challenges of the situation.

“Our team is working on a new concept which will be established in dialogue with the public,” she said.

People passing the museum are divided.

For Anton Glazkov, a 27-year-old teacher, closing the museum would be wrong because “war and works of art are not always linked”.

But Dmytro Cheliuk, 45, who runs a nearby clothes store, said “the time has come for us to de-Russify ourselves and remove the Russian empire from our streets”.

Oleg Slabospitsky, an activist, takes a hands-on approach to removing Russian from public spaces.

Several times a week since Ukraine’s 2014 revolution, the 33-year-old dons a high-visibility vest and hauls a stepladder around the city taking down overly Russian street signs like “Moscow Street”.

– ‘Language of the enemy’ –

“These kinds of initiatives must come from the people themselves,” he told AFP before setting out with a friend to unbolt three plaques on Moscow Street.

In Kyiv, famous for its long avenues, the team sometimes spend whole days “de-Russifying” city streets.

Kyiv City Hall recently voted to rename 142 streets which contained references to Russia. Another 345 streets await the same fate.

The street formerly known as “Moscow” now honours the Ostrozky Princes, a dynasty of 16th century Ukrainian politicians.

At Shevchenko University — damaged by a recent salvo of Russian missiles — management took down a plaque last August that honoured Bulgakov, who studied there a hundred years ago.

Oleksandr Bondarenko, who heads a Slavic studies department, said the measure is “understandable” as the plaque could offend passers-by who had lost loved ones in the war.

Ukraine’s school curricula no longer features Russian language courses, nor works of Russian writers. Instead, a new course on the war with Russia has been added.

The history of the USSR is also now presented through the prism of imperialism.

Bondarenko’s faculty did not enrol new Russian students this year because the literature and language programmes are currently being adapted.

“Courses on information warfare meanwhile are now at the heart of the curriculum,” said Bondarenko.

“In a hybrid war, like this, you have to learn the language of the enemy to know him well. Sworn translators will be in high demand at war crimes trials.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter