From the Editors: March 9 marks the 210th anniversary of Ukraine’s greatest poet and architect of its modern national identity –Taras Shevchenko. We are therefore reprinting an article by our Chief Editor that covers a little-known but very illuminating episode in his life.

A legendary Afro-American actor in the middle of the nineteenth century flees slavery and meets on the other side of the world Ukraine’s leading poet and recent political prisoner who had earlier been freed from serfdom. Imagine the inherent mutual understanding and solidarity between the two irrepressible artists, and the resulting cathartic and creative interaction.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

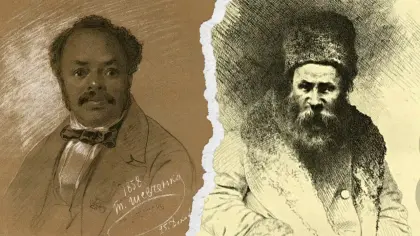

This is what actually occurred in the winter of 1858-59 when Ukraine’s greatest poet and national icon, Taras Shevchenko, met a remarkable black actor called Ira Aldridge in the Russian imperial capital Saint Petersburg. Their encounter resulted in an imminent, brief, but intense, friendship that was recorded in eyewitness accounts, sketches, and even a portrait of the American by the Ukrainian.

Aldridge was born in 1807 in New York into the family of a preacher. He had little hope of fulfilling his ambition of becoming an actor in a land where slavery and racial segregation were still the norm. Fortunately, as a young man he managed to emigrate to England where the climate was more liberal. During the next years when slavery was finally abolished in the British Empire (1834) the determined young American was able to fulfill his dream.

Aldridge began his career in small London theatres. But even in progressive England, the black actor was often subjected to racist abuse. He persevered and during the next three decades eventually became a star. He became the first black actor to play Shakespearean roles and was renowned as tragedian.

During his first European tour in 1852, Aldridge’s performances in “Hamlet,” “King Lear,” “Othello” and “The Merchant of Venice” consolidated his fame. He was showered with decorations and honors. In 1858, just as he was considering revisiting the country of his birth, he was invited by the Russian Imperial Theatre to play in St. Petersburg.

Here he soon met Shevchenko, who had just been freed after 10 years of captivity in the form of banishment and military service as an ordinary soldier in the Russian army in a remote area in present-day Kazakhstan. For a creative genius, this had been a cruel and degrading punishment from an autocratic Russian imperial system. After a decade of isolation from the cultural world, he could not get enough of theatre, opera and the world of the arts generally.

Shevchenko, a wonderfully talented artist respected in the top Russian artistic circles, had been arrested in 1847 in Kyiv for belonging to a secret patriotic society that had dared to elaborate the idea of a free and equal, democratic, partnership of Slavic nations – a United States of the Slavic world.

Shevchenko had been born a serf in 1814 in the Cherkasy region of Russian-ruled Ukraine. His talent as an artist unexpectedly brought him his freedom. In 1831 his master, a petty lord of the manor, brought him Shevchenko as his property to St. Petersburg where he allowed his servant to take art lessons.

Spotted sketching by a fellow-Ukrainian artist, Shevchenko’s talent was soon recognized at the highest level. In 1838 he was bought out of social bondage from his owner by a group of celebrated Russian artists and cultural figures.

While pursuing his career as an artist, Shevchenko remained true to his national and social origins. In his stirring poems he reminded Ukrainians who they were and instilled in them a desire for national and social emancipation. Like Aldridge he wanted to see an end to slavery in the form of serfdom, and he also wanted freedom for his native land.

When Shevchenko first saw Aldridge on stage for the first time – it was in the role of Othello – he was moved to tears. The fact that Shevchenko did not know English, the language in which Aldridge performed, did not diminish his appreciation of the great actor. An excited Shevchenko wrote to a friend: Aldridge “performs miracles on the stage.” He “makes Shakespeare come alive.”

Two days later, when Shevchenko and Aldridge met at the home of a Russian aristocrat, they hit it off immediately. Using sign language and with the help of friends acting as interpreters, they opened up to one another as if long-lost brothers. Aldridge could not even pronounce his new friend’s surname properly and dubbed him “the artist.”

Witnesses recorded their emotional fusion. Over the next two months, they shared stories about their roots, struggles and achievements, and even sang songs of their people to one another. In the theatre Shevchenko even disturbed the audience with expressions of his enthusiasm for Aldridge’s performances.

After Aldridge had played King Lear, a tearful Shevchenko went to his dressing room and started kissing the hands and face of the exhausted actor in gratitude.

Shevchenko, prematurely aged and his health impaired by the hardships he had been made to endure, died in March 1861 at the age of 47. Sadly, he did not see the abolition of serfdom in the Russian empire, which occurred seven days.

The American actor, however, perhaps inspired by Shevchenko, did visit Ukraine. Between 1861 and 1865 he performed in Kyiv, Odesa, Kharkiv, Poltava, Zhytomyr and Elizavetgrad (Kropyvnytskyi).

Press reports show that besides his celebrated role of Othello, audiences in Odesa and Zhytomyr particularly enjoyed his interpretation of the Jewish merchant Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.”

Although Aldridge lived to see the abolition of slavery in the United States in December 1865, he too never made it back to his homeland. He died while on tour in 1867 and is buried in the Polish city of Lodz.

Shevchenko’s portrait of Aldridge remains a tender reminder that the sense of humanity, freedom, solidarity, and devotion to artistic expression, transcend race and country of origin.

It is a modest, if priceless, testament to the chance friendship of two great and remarkable men and champions of freedom.

This article was originally published in the May 2019 issue of the monthly in-flight magazine of Ukraine’s International Airlines - Panorama and reprinted in Kyiv Post a year ago.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter