Note from the Editors. The following is the revised text of a presentation delivered by Kyiv Post’s Chief Editor Bohdan Nahaylo at a Ukrainian Historical Encounters Series Special Event entitled: “Russian-Ukrainian ‘Memory Wars’ in Western Academia and Media” held on Sept.16, 2023, at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York City during a panel discussion on “RU-UA Memory Wars in the Realms of Print Media, Broadcast Media and the Internet.”

Ladies and gentlemen, esteemed colleagues,

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

It’s an honor and pleasure to be here. Thank you to the organizers for inviting me. And good to see so many familiar distinguished faces and new ones.

I've been active as a British--born and educated journalist, writer and analyst of Ukrainian origin seeking to get Ukraine's case across to the outside world for almost 45 years, so in the course of my presentation I will also give examples about how I went about it.

Let’s begin with the historical context. Remember, Ukraine’s memory wars have not been limited to confronting Russian rapaciousness, but have in the past also involved other neighbors and, indeed, their friends and de facto auxiliaries in the world beyond.

Until relatively recently, Ukrainians were very much on the losing side of these wars. The outside world was unaware, oblivious or hostile to their aspirations and plight and readily absorbed the narratives that the enemies and oppressors of Ukraine – as a concept, movement, would-be state – promoted.

And their aim was to obscure and destroy it, both because Ukraine’s territory was a coveted prize and because the idea of a distinct nationally assertive Ukrainian people posed a threat and impediment to their imperial schemes.

And why were the Ukrainians losers in this regard? Because there was no Kyiv Post!

Let me clarify by rephrasing that. Because there was no post from Kyiv, in the sense of Ukraine not being able to make its voice heard in the outside world and to present its messages and case.

Journalism as diplomacy

Journalism and news, as we know, is about providing information, which in turn, depending on its quality and reception, shapes opinion and attitudes. It is the public and more direct cousin of diplomatic activity, as it were.

Yes, the Ukrainians had plenty to say, to protest about and propose. But generally, their narratives failed to reach and impact on the outside world; moreover, they retained an introspective, defensive tone, understandably replete with moral indignation, anger and frustration with what was perceived by them as an uncaring or even cynical world.

Certainly, the odds stacked against a people without an independent state able to protect its interests were overwhelming.

Diplomatic activity even during the period of Ukrainian Cossack statehood fell short of what with hindsight we imagine was called for to bolster Ukraine’s image and standing. Ironically, even Hetman Ivan Mazepa and his diplomatically industrious successor Pylyp Orlyk failed to make much of a dent on European consciousness, apart from the Swedes and some notable exceptions.

And in fairness, it took a great modern Frenchman and European, Voltaire, to notify in 1731 the world of the burgeoning Enlightenment – that “L’Ukraine a toujours aspiré à être libre” – Ukraine has always sought to be free.

And 150 years later, who in the outside world, apart from perhaps within certain Russian and Polish circles, were aware of the role of Ukraine’s revolutionary firebrand Taras Shevchenko and his call for a Ukrainian George Washington?

Until relatively recently, Ukrainians were very much on the losing side of the memory wars.

Hardly surprisingly, with Ukraine’s modern resurgence at the beginning of the 20th century obscured and little understood in the external world, it failed to bring about proper recognition and independent statehood.

Nevertheless, it did demonstrate its latent strength and political potential. Just as Pushkin had been wheeled out by despotic Russian tsardom to denounce Mazepa as a traitor and castigate Europe’s so-called “slanderers of Russia,” so in turn, during the 20th century, such internationally acclaimed Russian literary stars as Gorky, Bulgakov, Nabokov and Brodsky ridiculed the Ukrainian language and culture even as the new totalitarian Soviet imperialists sought so brutally to eradicate “Ukrainian nationalism.”

Divided modern Ukraine remained effectively muzzled, and fake news, so effectively used as early as 1926 by Moscow in Paris against the embodiment of Ukrainian would-be independent statehood, Symon Petliura and his followers, became the sidearm of terror.

Even the by now large Ukrainian diaspora proved largely ineffective in setting the record straight. In 1933, at the height of the Holodomor, it was the British and Canadian journalists Malcolm Muggeridge, Gareth Jones and Rhea Clyman who managed to get news of Stalin’s genocidal campaign onto the pages of some of the leading Western newspapers.

Emerging Ukrainian voices

After the ravages of the Second World War – with the ongoing resistance of the Ukrainians and the fact that in 1945 Stalin had willed Soviet Ukraine to become a founding member of the UN – were Ukrainians better understood in the outside world?

Not really. True, with the onset of the Cold War the US provided them with important new means to speak to their compatriots behind the Iron Curtain through the broadcasts of Radio Liberty to the diverse peoples of the Soviet Union (together with Radio Free Europe for the countries of Eastern Europe, known jointly as RFE-RL) and Voice of America. But their content was directed eastward, not to the Western world.

Even during the post-Stalin period, despite the considerable efforts of the Ukrainian diaspora, the attention of the Western media remained focused mainly on Russian and Jewish dissidents in the USSR. The fact that Ukrainians made up the largest share of the political prisoners and what they stood for were overlooked.

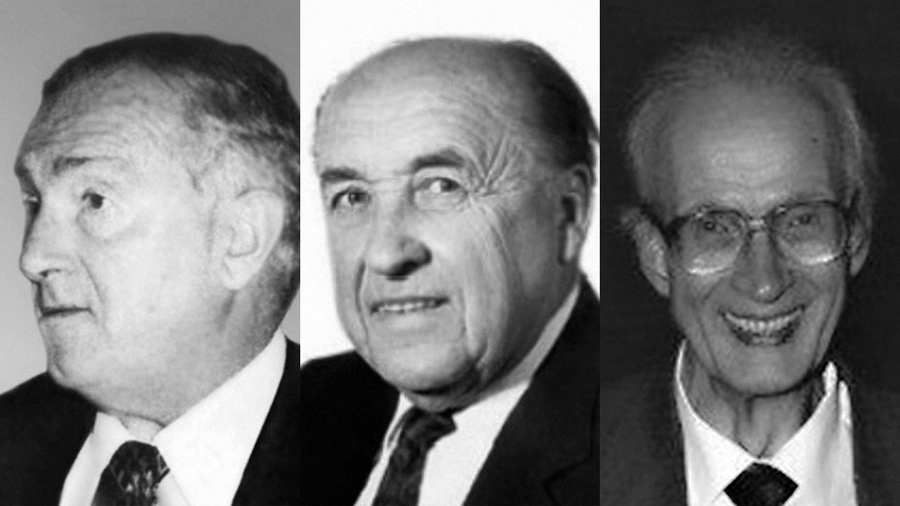

Ukrainian publicists active in Europe after WW II: from left to right: Borys Lewytzky, Bohdan Osadchuk, Victor Swoboda.

The voices of Ukrainian specialists and publicists from the older generation heard occasionally crying in the Western media wilderness were indeed few and far between.These included, most notably, Bohdan Osadchuk, aka Alexander Korab, in Switzerland’s Neu Zuricher Zeitung, Borys Lewytzky in West Germany, Victor Swoboda, aka M. Davies, Michael Brown, in Britain, and eventually, occasionally, Bohdan Bociurkiw and Roman Szporluk in North America.

The remarkable emergence in Ukraine of a new generation of patriotically-minded, democratic standard-bearers of the Ukrainian cause, promoted in a modernized form consistent with recently acknowledged universal norms, nevertheless galvanized elements within the Ukrainian diaspora, particularly among its youth.

In 1977, I was privileged to be invited to contribute an article on Ukrainian post-Stalin literary life to a publication by the Venice Biennale. And during the next three years, together with Victor Swoboda, we sought to publicize the fate of Ukrainian writers imprisoned by the Soviets in the London-based journal Index on Censorship, and to get them adopted by the International PEN Club - Chornovil, Svitlychny, Sverstiuk, Osadchy, Rudenko, Stus, Kalynets, and others.

The following year I became a Researcher for Amnesty International at its London headquarters responsible for defending "prisoners of concsience" in the USSR which opened new possibilities for me to get their plight known, including by forging ties with the international press.

In the first half of the 1980s, even preceding Gorbachev’s proclamation of glasnost, representatives of the new post-war generation trained in Western universities and journalism began to appear in the pages of some of the West’s most prestigious publications. Adrian Karatnycky and Alexander Motyl in the US, and myself in the UK, led the way.

The farsighted successful engagement of the American and British scholars James Mace and Robert Conquest by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute to produce a ground-breaking work on the Holodomor – Harvest of Sorrow, helped to broaden the front on the memory, or rather ideological, front with Russia.The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies based in Edmonton also began to play an important role in stimulating research and disseminating information on Ukraine's past and current situation.

The tactics used against us through the Soviet Union’s American agents of influence was to allege anti-Semitism or promotion of fascism

In April 1986 the massive shock disaster at the Chornobyl atomic power station not far from Kyiv occurred.and again there was confusion in the West - was "Chernobyl" in Russia or a regional offshoot of it called Ukraine? Quite a few of us attempted as best we could to clarify matters.

By the end of the 1980s, Gorbachev’s relaxation of controls precipitated the rapid growth of the various national democratic movements. The USSR was tottering.

To fill a massive lacuna in Western knowledge and awareness, I wrote a history of the Soviet Nationalities problem called Soviet Disunion, which was published in London and New York in 1990 and was then followed by Japanese, French and Italian editions. In July 1990 I was confident enough to tell CNN live that it was game over for the Soviet empire now that Ukraine had finally managed to re-assert itself.

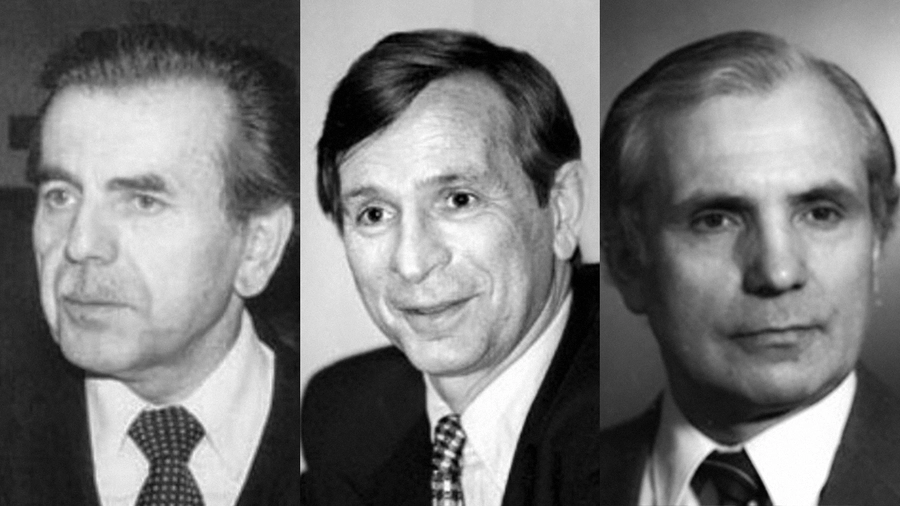

Ukrainian scholars active in the memory wars against Russia, from left to right: Bohdan Bociurkiw, Orest Subtelny, Roman Szporluk.

But even at this pivotal stage, it was not plain sailing. Two of the West’s most prominent leaders, the Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher and George Bush Senior, were not keen to see the Soviet Union disintegrate and would have preferred Gorbachev to salvage it via a new Union Treaty that the non-Russians did not want.

Meanwhile, the KGB was seeking to impede the work of Radio Liberty’s highly popular broadcasts bringing the truth and strengthening national awareness. Soviet jamming had stopped in November 1988, and I was appointed director of the service shortly afterwards as millions of people stayed glued to their radio sets.

The tactics used against us through the Soviet Union’s American agents of influence was to allege anti-Semitism or promotion of fascism because of our recalling, for example, the proclamation of the restoration of Ukraine’s independence by Bandera’s followers in Lviv on June 30, 1941.

But by now, these last-ditch efforts to scupper our work, had little impact. The bigger challenge was to build from scratch a network of reliable correspondents within Ukraine itself who could report the news reliably and regularly. It was for that purpose that the US management of RFE-RL sent me to Ukraine in June 1990. I was the first Radio Liberty official to be allowed into the imploding Soviet Union, which was to survive for a further year and a half.

Drawing on the activists of the newly emerged democratic platforms provided by Rukh and the Ukrainian Helsinki Union, we managed to establish an embryonic but effective team of stringers in Kyiv, Lviv, Moscow, and other cities. The stars were the former political prisoners Serhiy Naboka and his team in Kyiv, and Anatoly Dotsenko in Moscow. I was also fortunate to persuade such talented journalists and commentators as Vitaly Portnikov and Anatoly Strelyany to cooperate with us.

At this epoch-making time, Radio Liberty’s Ukrainian Service played a vital role in keeping Ukrainians at home and abroad informed about pertinent internal and external developments, serving as an amplifier for democratic voices, and integrating the large country by letting listeners in the east and north know what was going on in the west and south, and in Kyiv, and vice versa. It also helped with the restoration of national memory and raising national consciousness, thereby making a valuable contribution in the memory wars with Russia and in stimulating the development of independent media.

I should add that RFE-RL had an impressive Research Instititute which produced daily and weekly reports and analysis on what was happening in the Soviet Union, including on the growing efforts within it to uncover the truth about the past. The information was freely available in the West and was frequently conveyed eastwards. Roman Solchanyk and I played a prominent role there, as did for shorther periods, David Marples and Kathy Mihalisko.

Parts 2 and 3 to follow.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter