Mata Hari – the Dutch exotic dancer and legendary seductress – is regarded as the most famous woman spy of modern times, but a Ukrainian woman could also have claimed this title.

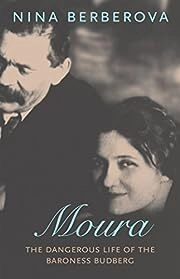

Baroness Moura Budberg, often called the "Russian" Mata Hari, was a more accomplished secret agent, active over several decades. An extraordinary femme fatale herself, she not only managed to work for several sides at once and survive, but also to have been the mistress of some of the leading literary and other engaging figures of the 20th century. She ended her days in London as a celebrated society hostess, translator of Anton Chekov, and scriptwriter for films starring Lawrence Olivier and James Mason.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Moura’s life reads like a thriller, and she deliberately shrouded it in mystery. Recent biographies by Russian and British authors have helped clear some of the mist, but the real captivating, if capricious, “baroness” remains elusive.

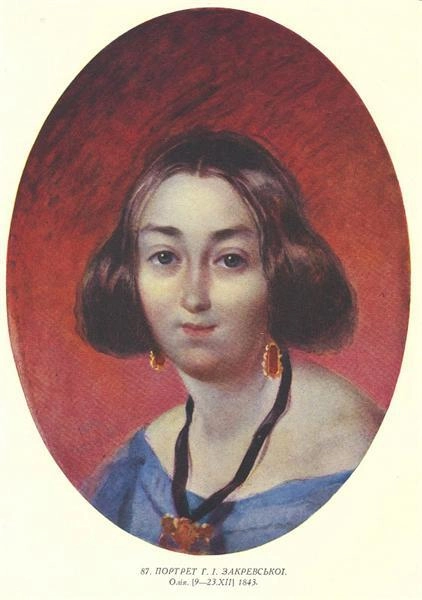

Moura was born in 1892 as Maria Zakrevska to a well-known and affluent Ukrainian family in the Poltava region. Her great-grandmother Hanna was the passionate, if secret, love of Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko. He visited the Zakrevsky estate, painted portraits of Hanna and her husband Platon, and devoted poems to her when in exile for his political activities. Poltava was to remain a center of the Ukrainian national movement and Shevchenko was its icon. Maria, nicknamed Moura (Mura) by her parents, was undoubtedly aware of this.

French Policy Playing Into Iranian and Russian Hands

Moura’s father Ihnatiy had a brilliant career in the Russian empire as a top legal specialist and high official but got into trouble for his reformist views. His daughter enjoyed a privileged upbringing. She had an Irish governess from Liverpool, a brother in the Russian diplomatic service in London, and she attended a boarding school in England. In 1911 she married Johann von Beckendorff, a diplomat at the Russian embassy in Berlin, who had an estate in Estonia.

Portrait of Hanna Zakrevska by Taras Shevchenko.

Following the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in February 1917 Moura was close to the moderate politician Alexander Kerensky, who from July of that year was Prime Minister in the Provisional Government. Rumors circulated that she was a German spy, Kerensky’s mistress; and after she obtained work in the British embassy, that she was the lover of the British diplomat Bruce Lockhart, later exposed as a foreign agent.

Her role, whether as a Soviet agent, or a double one, appears to have been that of an informer and a shaper of attitudes, rather than a spy in the classic sense of espionage

It was never clear whom Moura worked for. Did she help Kerensky escape from the Bolsheviks? While living with Lockhart, she was detained by the Bolsheviks in the summer of 1918 on suspicion of being a British spy, but was soon released. When Lockhart was himself arrested after being implicated with the “Ace of Spies” Sidney Reilly in a plot to kill Lenin, she managed to secure his release and safe return to Britain. At what price? Did she become the lover of the chief of the Bolshevik secret police (Cheka) in Moscow, Yakov Peters, and was it then that she agreed to work for it, or was she already its agent?

What happened next was a whirlwind of intrigue, danger and excitement. Moura’s husband was killed in 1919 in the newly independent Estonia, and she was stranded in Soviet Russia. Friends got Moura a job as Gorky’s secretary In Moscow and he immediately fell for her. She was to be his paramour and muse for the remaining 15 years or so of his life. Shortly after meeting Moura, Gorky was visited by the British literary star H.G. Wells, who promptly also fell in love with her. Their relationship as lovers was to last even longer, into the 1940s.

Gorky grew disillusioned with Bolshevik rule and left the country, ostensibly for medical treatment. Moura was to join him but was arrested in Estonia on suspicion of being a Soviet agent. Eventually, after being freed and in order to obtain an Estonian visa, she went through a fictitious marriage with a destitute Estonian aristocrat called Baron Budberg, arranged by Gorky (or most likely, given the fee paid to Beckendorff, the Cheka). Baroness Budberg divorced her spouse, kept the title, and remained Gorky’s mistress while intermittently pursuing her affair with Wells. Her role, whether as a Soviet agent, or a double one, appears to have been that of an informer and a shaper of attitudes, rather than a spy in the classic sense of espionage. Gorky loved her to the end even though he dubbed her the “Iron Lady.”

Although under pressure, Moura refused to hand over Gorky’s archive to Stalin until after the writer’s death in 1936. She herself, unlike Wells, had no illusions about the Soviet regime and settled down in London. The English socialist writer who in the 1920s had condemned repression in the USSR, interviewed Stalin in 1934 and now praised him. Wells, despite his advancing years, was a notorious womanizer, but he ensured that Moura and her children could live comfortably in their adopted country. Nevertheless, she turned down his offers of marriage. The “Russian baroness” was treated with suspicion by the British authorities but allowed during the Second World War to work as a translator for British propaganda units.

After the death of Wells in 1946, who left her a generous allowance, Moura finally obtained a British passport and settled into the role of a society hostess. At the beginning of the 1950s, when two British diplomats, her acquaintances, were exposed as Soviet spies, she was investigated by the British intelligence services. She warned them that Sir Anthony Blunt, an advisor to the Queen, was a Soviet spy, but was not believed. He was exposed only in 1964.

Britain’s MI5 cleared Moura, describing her in her file as “an unusually intelligent and amusing woman… a quite outstanding personality who can drink an amazing quantity, mostly gin.” She entertained some of the leading intellectual and artistic figures of the day in her London home, and at the same time continued to visit the Soviet Union. She died in 1974, at the age of 82, having first requested that her children destroy her papers.

The "Baroness" on old age in London.

In England, interest in Baroness Moura Beckendorff-Budberg was rekindled a few years ago after it became known that one of her relatives through her niece Kira, Nicholas Clegg, had become leader of the Liberal Democrat party and Deputy Prime Minister of England.

For those interested in Ukraine, it is even more fascinating to know that behind the mask she wore, this cosmopolitan “iron lady” and seductress was in fact the great grand-daughter of a distinguished Ukrainian beauty who had captured Taras Shevchenko’s heart.

This article was originally published in the March 2019 issue of Panorama, the in-flight magazine of Ukraine’s International Airlines.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter