With Russia now saying it’s willing to sink commercial trawlers on the Black Sea – and US officials saying it may target civilian ships too – here’s what you need to know.

What is the latest on what Russia says it will do?

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Russia’s Ministry for Defense yesterday announced that ships sailing on the Black Sea will now “be considered potential carriers of military cargo.”

- Find the most up-to-date war in ukraine update in the Kyiv Post's daily news items for today.

- Access the newest Ukraine news items published today.

It also said flag countries of vessels sailing to Ukraine will be considered as on Kyiv’s side.

That’s right – on grounds of suspicion, Russia is willing to blow the commercial trawlers flagged by countries such as China, India, Turkey, Egypt, Panama, and Greece out of the water.

But the situation may even be more intense. A senior US security official yesterday told AFP that Russia is considering attacking civilian ships on the Black Sea and putting the blame on Kyiv as part of “false flag” operations.

National Security Council spokesman Adam Hodge cited Russia's release of a video showing its forces detecting and destroying an “alleged Ukrainian sea mine.”

“Our information indicates that Russia laid additional sea mines in the approaches to Ukrainian ports,” he said, adding the allegation was based on newly declassified intelligence.

“We believe that this is a coordinated effort to justify any attacks against civilian ships in the Black Sea and lay blame on Ukraine for these attacks,” Hodge said.

‘If It Flies, It Flies’ – Russian-Built Shaheds, Numbers Up, Quality Down

Raising tensions even further, in the latest development Ukraine said on Thursday afternoon that ships going to Russian-controlled ports on the Black Sea would be seen as possibly carrying military cargo.

Ukraine's defense ministry said that "starting from 00:00 on July 21, 2023, all vessels in the Black Sea heading towards Russia's seaports and Ukrainian seaports located in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine may be considered by Ukraine as carrying military cargo, with all the associated risks".

What will be the impact of Russia blowing up the Black Sea grain deal?

Significant and varied is the answer that experts are giving.

First, if a ban on Black Sea shipping holds, the total amount of Ukraine’s grain output might go down by some 40 percent, according to grain market analysts.

Pre-war, Ukraine was one of the world’s largest grain exporters, supplying about 10 percent of the trade in wheat, about 15 percent of the corn market, and more than 40 percent of the sunflower oil market. Ukrainian farms fed 400 million people worldwide, according to the UN World Food Program.

Second, more limitations on grain exports from Ukraine will impact both food prices and global food supplies. One expert said that “Ukraine’s volumes have helped the inflated post-invasion prices return to levels that are affordable for those countries in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.”

From February to June 2022, at least 25 million tons of Ukrainian grain intended for global markets got trapped in Ukraine because of Russia’s naval blockade, causing food prices to jump. The UN has estimated that the grain deal has reduced food prices by more than 23 percent since March 2022.

Now the deal is at least temporarily dead, wheat prices on the European stock exchange soared Wednesday, rising 8.2 percent, while corn prices were up 5.4 percent. Chicago wheat futures, a global benchmark, are up about 17 percent since Russia left the deal which is biggest jump since 2012.

And the amount of grain available for impoverished countries that rely on international aid programs for grain is going to go down.

Of the roughly 33 million tonnes Ukraine shipped since the deal has been in place about 17 per cent has been exported to Africa.

More than 500,000 tonnes of the wheat shipped was through the World Food Program to support its humanitarian operations in hunger-stricken spots, such as Yemen, Sudan and Afghanistan.

Third, Russia has used the end of the deal to make the Black Sea a renewed front of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In addition to its bluster about ships at sea, Russia stepped up – both physically and psychologically – assaults on Ukraine’s agricultural and maritime sectors. This is timed as the main Ukrainian harvest is about to come in.

For three nights in a row, Russia has conducted extensive aerial strikes – using drones and cruise missiles – on Odesa, Ukraine’s key Black Sea port. Another important port, Mykolayiv, was hit last night with at least nine people injured.

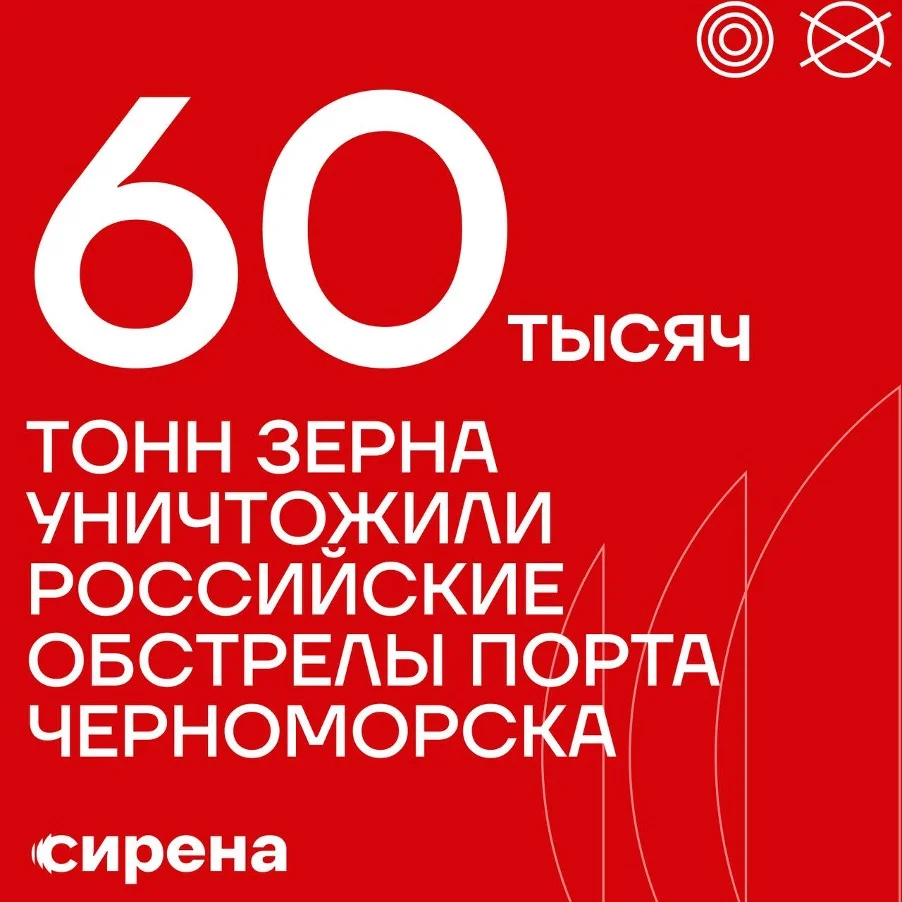

Kyiv said that one of the Russian strikes destroyed 60,000 tonnes of grain waiting to be shipped to China, which is the broad equivalent of two ships’ worth.

Russian social and State media jumped on the figure and produced celebratory posts and graphics.

Fourth, the closure of the sea route used to export Ukrainian grain reignited fears among Ukraine’s European neighbors of being flooded with allegedly “cheap” grain. The Kremlin well knows the tensions that grain creates among Ukraine and its allies. In June, Brussels agreed to allow Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania to restrict imports of grain from Ukraine through September

Poland, facing elections in September and needing to appease farmers, pre-emptively yesterday announced it would close its border if the current moratorium is lifted.

Why did Russia exit the deal?

Who knows. Given its authoritarian and Mafia-like decision-making, it’s always hard to say what logic drives the Kremlin’s decisions.

An Australian editorialist went to town on the Russian leader: “Vladimir Putin’s aim in unilaterally abandoning the Black Sea Grain Initiative that has allowed Ukraine to continue exporting wheat and other crops despite the war is as clear as it is utterly cynical and inhumane.

"It would be hard to think of a deliberate strategy by any regime that is more appalling.”

On paper, Putin said that Russia’s requirements to improve the grain deal were not met. For the deal to remain, he wanted the West to allow Russia’s agricultural bank access to the SWIFT international messaging service, the lifting of sanctions on maritime insurance, on supply of agricultural machinery, and on fertilizer companies, and the reopening of an ammonia pipeline that passes through Ukraine.

The pipeline is part of the TogliattiAzot company which is one of Russia’s largest ammonia and fertilizer producers. It claims to have 11 percent of the global market for ammonia with its primary markets being in India and Brazil.

Back in May, Kyiv Post exclusively reported about TogliattiAzot being owned and operated by Putin’s crony, Dmitry Mazepin. Mazepin is, according to Forbes, one of Russia’s wealthiest 100 people with a personal fortune over $900 million.

Despite the closure of the pipeline, Russian fertilizer exports have soared by 70 percent to $16.7 billion since the full-scale war started.

How will Ukraine and its allies respond and cope?

Ukraine and others have said that Russia and Putin are weaponizing the world’s food supply, but that Ukraine is prepared to continue grain exports despite the end of the deal and called on other countries to help.

According to the experts, Ukraine, which shipped 90 percent of its grain by sea pre-war, has been shipping an increasing volume of its exports by land and river, using trains and barges.

“While it could ramp up those volumes further, it is more costly and takes a lot longer to get the commodities to the market and the lower returns to the farmers make planting less attractive, threatening future production,” Stephen Bartholomeuz, a commodity and trade specialist wrote.

Beyond the words, Ukraine, international bodies, and its allies are likely to look at several options to keep grain flowing.

These include:

· Convincing the UN to sail ships under its flag or its direct protection – a long shot that could only happen via a majority vote of the General Assembly given Russia’s veto power on the UN Security Council.

· Convincing Turkey to do so – but also a long shot given it is a NATO member.

· Expanding use of an alternative maritime route through Romanian waters of the Black Sea and then road transport – and Ukraine has now formally approached the UN in that regard.

· Working with Turkey, whose trade with Russia has soared since the invasion, or China, the major buyer of Ukraine’s grain, to make another attempt to bring the deal back to the table.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter