And so, it started

The world stood still on the night of June 6, 1944, waiting to hear news from the front line in France following the launch of Operation Overlord, the counteroffensive that began the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe, and came to be known as the D-Day Landings. The operation combined vast naval, air and land assets involving some 156,000 British, American, Canadian and other allied forces landing on five beaches in Normandy in northern France.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Many unarmed journalists from around the world stood alongside the soldiers who were to fight their way up the beaches, embedded in and working alongside Allied military units. They risked everything to make sure that those back home learned, by way of nightly first-hand accounts, what their loved ones were facing on the beaches, in the fields and in the towns of Normandy. Who were these men and women? What dangers did they face and what horrors did they report on daily?

A few minutes after midnight on June 5/6, 1944, a BBC correspondent, Richard Dimbleby, who was to become a famous TV presenter, witnessed around 20 aircraft taking off at the start of the "plan which they had been working and sweating and slaving at for months.”

He gave a radio report of what he had seen later in the evening; his tone was one of admiration for the men and their aircraft as they headed off into the night.

On one of those planes was Wright Bryan, a war correspondent from the Atlanta Journal and NBC Radio. Bryan had covered the war in Europe for two years before being tasked to fly out with US paratroopers and to watch them jump into Normandy. He was to scoop all other reporters by broadcasting the first eyewitness account of D-Day on his return from witnessing the jump.

On another plane was another BBC reporter, who was to parachute in with the paratroopers who lined either side of the Douglas C-47 aircraft. His report was exciting, moving and optimistic: “[These] are some of the toughest and finest and bravest men that we have in Britain and they go out today to face their greatest trial.”

General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, known as “Ike” to his troops, believed that “an informed public will help win the war,” and was happy to give journalists as much access as possible. Another BBC war correspondent, Robert Barr, was embedded in Eisenhower’s headquarters and followed the General from D-Day until the end of the war.

On the night the invasion began, Barr described watching US paratroopers boarding another aircraft:

“Their faces were darkened with cocoa; sheathed knives were strapped to their ankles; tommy guns strapped to their waists; bandoliers and hand grenades, coils of rope, pick handles, spades, rubber dinghies hung around them and a few personal oddments, like the lad who was taking a newspaper to read on the plane.”

Barr commented that these men had repeated the process “20, 30, 40 times some of them, but it had never been quite like this before”. This was, in fact, the first combat jump for most of these young Americans.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1943

Credit: Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The D-Day Landing

At 9 pm on D-Day, King George VI made a speech to rally the nation: “After nearly five years of toil and suffering, we must renew that crusading impulse on which we entered the war and met its darkest hour. We and our Allies are sure that our fight is against evil and for a world in which goodness and honor may be the foundation of the life of men in every land.”

When he had finished millions of Britons remained gathered around their radios to hear announcer John Snagge introduce Howard Marshall, who had spent the day alongside the soldiers on the Normandy beaches, and now reported through the radio on what he had seen advancing across the beaches of Normandy.

“I've just come back from the beaches and as I've been in the sea twice, I'm sitting in my soaked through clothes with no notes at all, all my notes are at the bottom of the sea.”

The day had started just after dawn so, in the dim morning light and while in a landing craft in rough seas, Marshall could see troops opening fire on the beach and explosions. He reported that he could hear planes overhead, could see explosions in the water, that the Germans had placed “formidable prongs, many of them tipped with mines” in the water, designed to sink anything that might come into contact with them.

“And suddenly, as we tried to get between two of these tripod defense systems of the Germans, our craft swung and we touched a mine, there was a very loud explosion, a shudder and … water began pouring in.”

He was to describe in great, captivating detail what the troops had encountered on that first brutal encounter with the enemy. As Marshall spoke, he accurately and clearly described a hellish scene to civilians that, in those pre-Hollywood blockbuster movies days, had no frame of reference for the scenes that he was relating.

The D-Day landings

Photo: Normandy tourism

Censorship

Much of the output of journalists, who were hoping to convey positive stories, faced censorship by the Ministry of Defence who wanted to allow the press to report on the war without putting national security at risk.

Reports that could reveal information such as the exact location of troops and their objectives or that could be surmised from such things as weather reports could not be published.

Newspaper articles had to be submitted to the Ministry of Information which would be scrutinized, passages censored where necessary and finally stamped as approved before being returned for publishing.

Women were there too

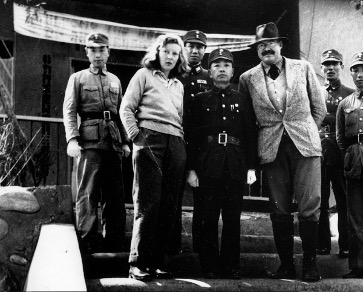

Another war correspondent who risked it all to report back from the frontline of Operation Overlord was a woman, the American journalist Martha Gellhorn, who was once married to Ernest Hemingway. She is considered to be one of the greatest correspondents of the 20th century who was not only active during WWII but covered other conflicts - the Spanish Civil War, the Vietnam War, the Arab-Israel conflicts and the US invasion of Panama in 1989 at the age of 80, only stopping as her eyesight failed.

Initially not accepted as a correspondent for D-Day, Gellhorn stowed away on a hospital ship, disguising herself as a stretcher-bearer before becoming the only woman to witness the D-Day Landings in person and the large numbers of casualties being brought to the ship.

She witnessed great swathes of casualties coming back from battle.

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway covering the Sino-Japanese war in 1941

Photo: wikicommons

Another female journalist who covered the invasion was a former model, Lee Miller. She was the only woman to obtain US forces accreditation as a war correspondent, in 1942. Much to her chagrin, however, she was not allowed to reach the Normandy front until mid-June 1944. She was able, however, equipped with just a small portable typewriter and a rudimentary camera to publish one of the most famous reports of the period. In August 1944 the British Vogue magazine published her story entitled “Unarmed Warriors,” in which she described in emotional terms the life of those working in an American evacuation hospital set up in the fields just inland from Omaha Beach. Tribute is paid to her and the stories she told in the space dedicated to war correspondents at the Bayeux museum.

Lee Miller, Normandy, France, 1944.

Photo: Lee Miller Archives

A picture saves a thousand words

Very few journalists had initially received accreditation to accompany Allied troops during the first phase of invasion. Robert Capa, a photojournalist working for the American “Life” magazine, was one of the “lucky” few. He was embedded with the US First Army’s, 5th Corps and accompanied the troops landing on the zone christened “Omaha beach”. Equipped with his small, sturdy Leica camera Capa landed with the first wave of the assault at about 6am.

He took dozens of photos in the midst of extremely fierce fighting. He seemed to show no fear and told those who asked why he got so close: “If your pictures aren’t good enough you aren’t close enough”.

There is a memorial stone to Robert Capa next to the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy, a reminder of his journalistic work covering the events during the summer of 1944 and also more generally the work to which he devoted his life until he was killed in 1954.

The Original Tweeter?

In September 1944, a pigeon called Gustav received a PDSA Dickin Medal, the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross for: “… delivering the first message from the Normandy Beaches from a ship off the beach-head while serving with the RAF on 6 June 1944.”

Thousands of pigeons were used during both the First and Second World Wars to bring back vital progress reports. Gustav was one of 32 pigeons to receive the Dickin Medal.

As D-Day started, the invasion fleet was under radio silence to avoid enemy detection. Carrier pigeons, well known for their homing ability, speed and altitude, were used to pass vital messages under such circumstances. A small piece of paper was placed in a tiny canister that was attached to Gustav’s leg before he was released to fly the 250 kilometers across the Channel to RAF Thorney Island near Chichester, West Sussex. The flight reportedly took only five hours and 16 minutes and provided the first confirmation of the first successful landings.

With thanks to the British Forces Network, the Bayeux Museum, the Lee Miller Archives.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter