Easter in Ukraine this year is being celebrated on April 16, in line with the Julian calendar used by the Orthodox and Eastern Rite churches.

As the war with Russia drags on, Ukrainians’ resentment against Moscow has become increasingly visible throughout society. The religious sphere is no exception.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

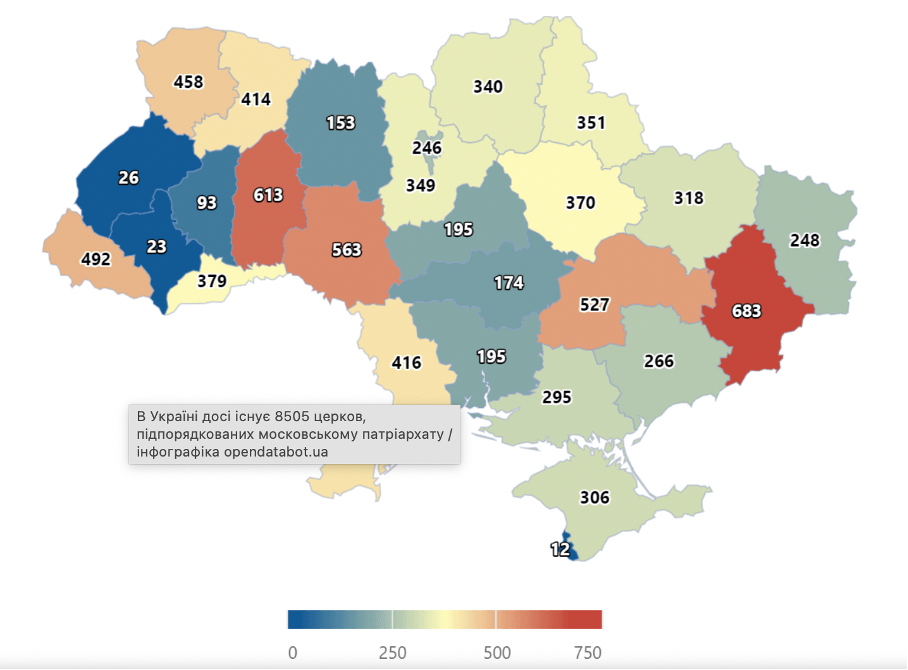

Every day there are more reports of parishes switching from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) to the independent and patriotic Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU). Since the full-scale invasion on Feb. 24, 2024, at least 214 parishes have switched over, 63 already in 2023.

In many cases, the change is not entirely peaceful. Indeed, the list of conflicts and violent incidents at churches keeps growing.

What’s the difference?

To most casual observers who don’t understand the language, it would be hard to tell the difference between the UOC-MP and the OCU. The rites and theology are the same. The only observable difference is the language of the liturgy; the UOC-MP celebrates in Russian, the OCU primarily in Ukrainian, though at times in Church Slavonic.

But what actually makes all the difference between the churches is ecclesiastical jurisdiction. In other words, history and politics.

And if, as Carl von Clausewitz is so often quoted, “war is politics with other means,” then churches in Ukraine have been veering off into that realm of other means for many decades.

Over the years, and especially since the OCU was conferred with canonical status by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in 2019, more and more believers and parishes have moved away from the Moscow-linked UOC-MP.

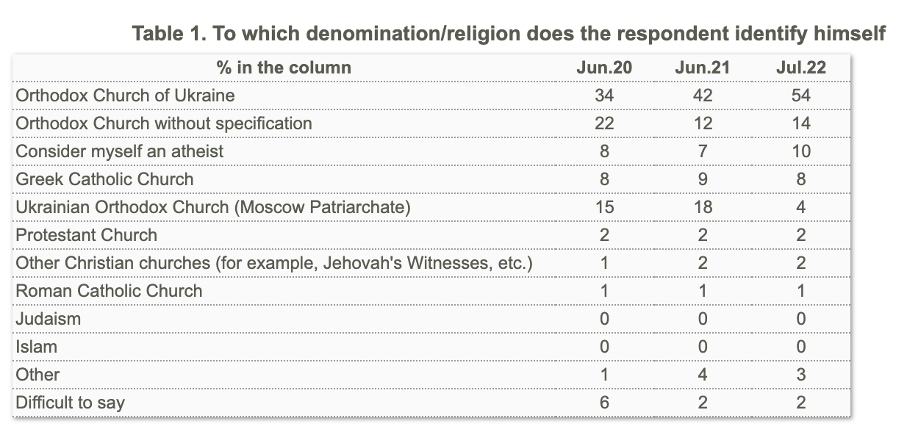

According to surveys conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), the number Ukrainians who identified as members of the OCU has grown by 20 percentage points from June 2020 to July 2022. In response to the question “To which denomination or religion, if any, do you belong?” 54 percent said the OCU.

By contrast, the Moscow-linked church saw a drop of 14 percentage points since the war started. In July 2022, only 4 percent of Ukrainians identified themselves as belonging to the UOC-MP.

KIIS notes that “although the UOC-MP retains de facto control over the majority of parishes, at the same time it has suffered significant reputational losses in the minds of Ukrainians (of course, due to associations with the Russian aggressor).”

A more recent KIIS poll conducted from December 4-27, 2022, asked Ukrainians throughout the country what authorities should do with the UOC-MP.

The results of the poll showed that 78 percent of Ukrainians believe the state should intervene in the activities of the UOC-MP to a greater or lesser degree. In particular, 54 percent believe that the UOC-MP should be completely banned in Ukraine. Another 24 percent are in favor of a somewhat “softer” approach, which does not involve a complete ban, but involves the establishment of state control and supervision.

Only 12 percent of respondents believe that nothing should be done, that the authorities should not interfere in the general affairs of the UOC-MP and only certain individual offenses should be investigated.

Why politics

What drove Volodymyr the Great to baptize his subjects in 988, thus ushering Kyivan Rus into Christendom? Undoubtedly, aside from any spiritual considerations,

Volodymyr was a prince of the Rurik dynasty, which came from Varangian stock, originally from what are now Sweden and Norway. In order to control territory populated by disparate Slavic and non-

Christianity of the Orthodox type imported via Byzantium and under the Patriarch of Constantinople took hold in proto-Ukraine and was crucial in the spread of literacy and culture.

Kyivan Rus was destroyed by the Mongols in 1240 and Byzantium/Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. The Orthodox faith persevered in what became known as Ukrainian lands, even though the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which gradually established control over them did not tolerate it nor empower its political representatives.

In 1596 the Ukrainian Orthodox hierarchy agreed to recognize the jurisdiction of the Pope and created what would become the Ukrainian Catholic Church of the Greek rite. But many of their faithful refused to follow this route, and maintained the tradition of the Orthodox faith inherited from Kyivan Rus. It was they who in the first half of the seventeenth century established the first Orthodox Christian university in eastern Europe, the famed Kyiv Mohyla Academy.

The situation was further complicated in the late seventeenth century when a resurgent Muscovy, having taken control of much of Ukraine, claimed for its self-proclaimed Moscow Patriarchate control over Ukraine’s Orthodox who until then had accepted the Patriarch of Constantinople as the spiritual head of the ecumenical Orthodox Church

Separating religion from politics

So, as we see, over the centuries religion and politics throughout Europe were intimately entwined. And while much of the West has gone to great lengths to establish a separation between church and state, this was not the case in the Russian Empire.

In fact, during the Soviet period, the Orthodox Church – as a guardian of imperial ideology – was merely forcibly supplanted by the Communist Party. Purged and regimented it was made into a de facto auxiliary for the purposes of social control, Russification and, yes, Russian imperialism, however disguised.

Today, Russia is in the throes of a reactionary ideological moveme

As historian Timothy Snyder put it in a recent lecture: “In this ideological system, there’s only one part of the world which has not been thoroughly corrupted and destroyed and fragmented, and that part of the world is Russia. So in this system, the mission of Russia is to restore unity to this world.” The implications of this mission, Snyder argues, effectively allow Russia to justify all their crimes and horrors.

Clearly, Ukrainians and most of the world have rejected that ideology as sheer lunacy.

Religion, national consciousness and enduring Russian imperialism

Although Ukraine today is a secular, multi-ethnic, multi-confessional state in which no one faith has a privileged position (unlike the Orthodox Church in Russia), religion has always played a significant role in the development of Ukrainian national consciousness.

Taras Shevchenko – the nineteenth-ce

In 1920, the creation of the first Autocephalous (self-governing)

In western regions, during Austro-Hungarian rule in the nineteenth century and Polish domination in the interwar-period in the first half of the following century, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was a significant factor in maintaining the language, culture and traditional ties to Western Europe – so much so that in 1946 Moscow banned it when it had taken control of the area.

When the Soviet Union was breaking up at the end of the 1980s, not only did Ukraine seek to free itself from Russian tutelage in the political and economic sense, but also in the religious realm. The Ukrainian Catholic Church reemerged from the catacombs and was legalized, and the Autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church experienced a regeneration.

Mstsyslav, a nephew of Petliura, and a prominent Ukrainian Orthodox Church hierarch (including being the first hierarch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, and one of the Metropolitan's of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the USA), who visited Kyiv in 1990, became the first Patriarch of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, regarded as schismatic by Moscow and its followers.

With the collapse of the Soviet empire, the Russian Orthodox Church through its local proxies remained an important source of external influence in the newly independent states with a Christian heritage.

Ukraine’s leaders at the time preferred not to antagonize their northern neighbor and permitted the pro-Russian Orthodox church on their territory to not only continue its existence but also to retain possession of such key religious and cultural sites as the Kyiv Pechersk and Pochaiv Lavras (major monasteries).

In July 1995, Patriarch Mstyslav’s

He was succeeded by Metropolitan Filaret (Denysenko), a former pro-Moscow loyalist who split ranks when Ukraine declared its independence. He was enthroned as Patriarch of Kyiv and All Rus-Ukraine on Oct. 22, 1995.

In 2019, during the presidency of Petro Poroshenko, the Patriarch of Constantinople restored his spiritual ties and primacy with the Orthodox Church of Ukraine which by now has united all the Orthodox but the pro-Russian church.

Given this historical background, the current tug-off war on the religious landscape is merely a continuation of the process of Ukraine breaking away from Moscow’s 369-year grip – decolonization in its latest form.

What happens now?

Initially, after the full-scale Russian attack on Feb. 24, 2022, the government, while cracking down on pro-Russian TV channels and oligarchs, seemed to go out of its way to avoid exacerbating latent religious tensions.

However, from the recent crackdown on the UOC-MP, it appears that the government and most of society have lost patience with what they regard as a residual fifth column collaborating with Moscow.

In an report published by Ukrainska Pravda on April 7, after searches by the security forces, more than 20 high-ranking clergymen of the UOC-MP were found to have Russian passports.

Among those 20 priests is the head of the UOC-MP, Metropolitan Onufriy (born Orest Berezovsky). The 78-year-old primate, born near Chernivtsi, in western Ukraine, is seen by many church insiders as the key to what happens with the Orthodox Churches in Ukraine.

Shortly after the full-scale invasion, Onufriy announced that the UOC-MP was breaking with Moscow because of the Russian Orthodox Church and their Patriarch Kirill’s support for the war. For the previous eight years Onufriy steadfastly refused to denounce Moscow and repeatedly insisted that Ukraine was in “a civil war,” even suggesting, as many pro-Moscow priests still do, that Ukraine is being punished by God.

Few people, apart from Onufriy’s devoted followers, bought into what most interpreted as a political public relations gambit on Onufriy’s part – notwithstanding his sincere dismay over the war.

“This church [UOC-MP] has developed a deep dependence on one personality, its primate Metropolitan Onufriy,” said Cyril Hovorun, an Orthodox Ukrainian theologian and archimandrite at Sankt Ignatios College in Stockholm, who for 10 years was the private secretary and closest theological counselor to Patriarch Kirill of Moscow.

Hovorun knew Onufriy personally and added: “He is a very charismatic figure, and an unpredictable one, even for himself. So, [the future of the Church] depends, I think, completely on him. This complete unaccountability of Onufriy to the rest of the Church when he does whatever he wants, and everyone follows, is one of the main reasons for the crisis.”

Now that the religious question has come to a head, the Zelensky government has initiated the legal process to gradually evict the UOC-MP from state-owned territory and buildings.

“I am sure the SBU [Ukraine’s Security Service] knew about [Onufriy’s] Russian citizenship a long time ago and decided to use it now,” Hovorun told Kyiv Post. “I think it means that pressure on him has dramatically increased. Zelensky may strip him of Ukrainian citizenship, which will impede him to function as a primate of the Church.”

Most analysts agree that the only direction forward is to encourage some sort of rapprochement – or even a union – between the two Orthodox churches. But it will only work if Moscow is cut out of the picture – not just in name, but in practice.

In the longer term, what many patriotic Ukrainian Orthodox and Catholic believers aspire to is a Kyivan Patriarchate which would unite them and allow them to reaffirm Ukraine’s cultural and religious patrimony and sovereignty as a nation and state.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter