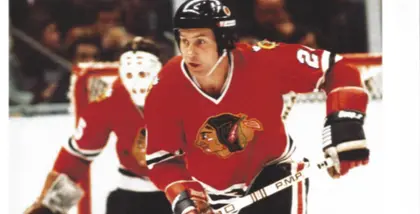

Former NHL hockey star Cliff Koroll, a Saskatchewan native and now head of the Chicago Blackhawks’ Alumni Association, is a Canadian of Ukrainian descent. In retirement, Koroll, now aged 76, is rediscovering his forgotten roots.

“All the troubles with Russia came to the forefront, [and] I became more sympathetic toward the situation,” he told the KyivPost of the full-scale of invasion.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

He could only imagine “how tough people have it there [in Ukraine]…it doesn’t make sense, I don’t know what Putin is trying to accomplish and it made me realize how lucky I am where I am at.”

Koroll continued: “The poor people are going through hell with this fiasco and don’t know when it’s going to end…it made me more aware of Ukraine, I feel sad for what the people have to face and what they’re going through.”

In March, Koroll, helped secure Blackhawks tickets for a delegation of 33 Ukrainians (26 minors and six adults) from the displaced Kharkiv Berserkers hockey club. They came from Ukraine for a charity tournament to help raise funds to help them find more permanent facilities because their ice rink was damaged by Russian artillery.

Chicago Blackhawks Alumni Association president and former NHL star Cliff Koroll holds a plaque presented to him from the Ukrainian Sports Hall of Fame by the organization’s local representative Taras Haliw with Ukrainian-American John Jaresko (Ukrainian hockey jersey) on March 5 at the United Center in Chicago.CREDIT: Courtesy of the Chicago Blackhawks

Perhaps his most cherished Ukrainian item is a “bulava,” a kozak mace, that the Ukrainian History Museum presented to him. It has become the first of his possessions to symbolize Ukraine.

Road to NHL

Koroll’s journey to professional hockey started in Canora, a rural town in the western Canadian province of Saskatchewan where winters are brutal yet ideal for outdoor hockey.

The Ukrainian Canadian spent his first three years there, sharing a bedroom with four other siblings inside a shack with approximately 50 square meters of living space, before moving to Saskatoon, the province’s largest city and capital when his father found a job with a railroad company.

Future Chicago Blackhawks player Cliff Koroll first lived in this 24-foot-by-24-foot cottage in the Saskatchewanian provincial town of Canora in Canada after he was born in 1946 and whose grandparents were both from the Bukovyna region of Ukraine.CREDIT: Courtesy of Elaine Koroll

It was a step up and the transition would propel him to eventually embrace hockey – Canada’s national sport – where he would make lifelong friends.

Koroll’s surname in Ukrainian means “king” and both his grandparents had emigrated from Bukovyna, now mostly sitting in the southwestern Chernivtsi region of Ukraine.

An all-round athlete, Koroll left Canada at the age of 17 years with two other hometown friends to study at university in the city of Denver in the U.S. At the time the National Hockey League (NHL) was still in its infancy and comprised of only the “original six” clubs of the Boston Bruins, Chicago Blackhawks, Detroit Red Wings, Montreal Canadiens, New York Rangers and Toronto Maple Leafs.

“My main motivation was the love of the sport [hockey],” he told Kyiv Post in an audio interview. “I also had the chance to play football on scholarship in North Dakota and had a Class A baseball contract waiting for me with the Minnesota Twins, if I wanted it.”

On crossing the border into the U.S., Koroll left behind his Ukrainian relatives and his weekly Ukrainian language studies.

“I was pushed by my parents to learn the language … unfortunately, I lost all of it without practicing it,” he said.

As he became immersed in college life in the Rocky Mountain West, his university studies and hockey growth took priority. In time he forgot the language.

“It was difficult getting back into the swing of things of my Ukrainian roots,” Koroll said.

On graduation, he was drafted by the Chicago Blackhawks, playing only one year at the NHL team’s farm team, in Dallas, before being promoted to the professional team the following year together with homeboy and former college roommate, Keith Magnuson, with whom he would jointly establish the Chicago Blackhawks Alumni Association in 1988 together with Stanley Cup winner and NHL Hall of Famer Stan Mikita.

After promotion to the Blackhawks roster in the 1969-1970 season, Koroll said his career and off-season conditioning, as well as his family life “took priority” – he has three children. “I kind of devoted attention to that.”

Career

Koroll’s statistics over an 11-year career would normally qualify him for acceptance into the NHL Hall of Fame, but he never won a Stanley Cup after two appearances in the finals.

As a winger, he scored 208 goals in 814 games played, had 254 assists and a total of 462 career points.

“Koroll’s other career highlights included playing in 404 consecutive games, and was the first Chicago rookie to register a hat trick,” the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame says.

He then went on to coach the Blackhawks as an assistant for another six seasons and would mentor Ukrainian American player Ed Olczyk and future hall of famer Chris Chelios.

The one void in his life remains “not winning the Stanley Cup,” Koroll said, who played in two finals, both times losing to the Montreal Canadiens in 1971 and 1973.

Roots

His heritage was never lost on him and he knew other NHL players of Ukrainian descent “were out there.”

On his own team, Eric Nesternko, who won the Stanley Cup in 1961, gave Koroll advice when he was starting out. His father was from Chernihiv Oblast and fought against the Bolsheviks on the side of the Ukrainian National Republic in the early 20th century.

“It wasn’t any secret” that Ukrainians were in the NHL, he said. “Nesterenko was a right winger like me and helped me out in different aspects of the game but we never really spoke Ukrainian to each other.”

However, Koroll continued, the Ukrainian roots of other players was “in the back of your mind, like ‘he is one of our people’.”

But when the puck toss started the game, he said, “in opposition, you approach the game the same way … you knew they [Ukrainians] were out there, but you had to drop what you’re doing” and play.

A Ukrainian documentary film called, “UKE,” released in 2020 profiled NHL players of Ukrainian descent and found that at least 50 players of Ukrainian extraction had hoisted the Stanley Cup during their careers, including Wayne Gretzky, also an inductee of the Ukrainian Sports Hall of Fame.

Players of Ukrainian heritage, the movie’s production researchers found, are the third largest nationality group among Stanley Cup winners after Americans and Canadians, respectively.

Upbringing

Koroll was a child of what was considered to be the first wave of Ukrainian immigrants to Canada who arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who were given free plots of land to farm, mostly in the western provinces where the soil wasn’t as fertile as in their homeland.

Accounts from that time tell of local farmers who laughed at how the Ukrainian settlers would dig cellars underneath the land, as they did in Ukraine to store food. The ground had provided natural insulation even during the harsh, cold winters that far north.

Most homes in the area at that time were made of wood and didn’t offer much insulation.

Some like Koroll and Ukrainian Canadians who grew up in that environment would eventually make it into the NHL.

“It was something like a 1 percent chance back then because the league was made up of only six teams,” he said. “I’ve been very fortunate, I’ve been recognized for multiple hall fame awards, by the Chicago community, by Canada and Saskatchewan.”

He is a 2017 inductee into the Pennsylvania-based Ukrainian Sports Hall of Fame and received the plaque award in person on March 5 at a Blackhawks game in Chicago.

To play hockey at university, top educational performance was a criterion, otherwise he wasn’t allowed to play, in addition to attending weekly language courses.

Back then, a grade of “good” was almost necessary to compete and two consecutive grades of the middle “fair rating” would disqualify you from playing.

“Before, we played every Friday night, some 15 games a year; nowadays kids play 60 games before Christmas,” Koroll said. “It taught us discipline, to keep your nose clean and not get into trouble. That assisted me through my hockey career.”

Giving back

As the president of the Chicago Blackhawks Alumni Association, Koroll says the group has raised more than $2 million worth of scholarships for promising high school graduates who play hockey “but not necessarily the best ones.”

Scholarships are handed to those “who do community work, have character and good recommendations – we’ve given about 115 scholarships and we support other charities,” he said.

Ukraine relatives

His sister-in-law Elaine Koroll researched their family history back to the late 19th century and to the Bukovyna region of southwestern Ukraine.

Both his grandparents hailed from there.

Stefan Korol was born in 1875 in the village of Tovtriv and came to Canada in 1901 at the age of 26.

His grandson told the KyivPost that Stefan “had only enough money to get to Winnipeg” and ended up “walking 500 miles” to get to his destination further west, all the while looking for work along the railroad track. Sometimes people would throw him sandwiches from the train.”

Cliff Koroll recalled that his grandfather’s daily routine was to walk, check the cattle and milk them, after which he would go mushroom picking and would return to the homestead “with a cap full of mushrooms.”

Elaine Koroll wrote that Koroll’s grandmother, Eufimma Kuruliak, was born in the village of Doroshevtsi in December 1888 and came to Canada with her parents at the age of eight.

She “would never work on Sunday … Food was always prepared on Saturday to feed family who came to visit on Sunday,” family research shows.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter