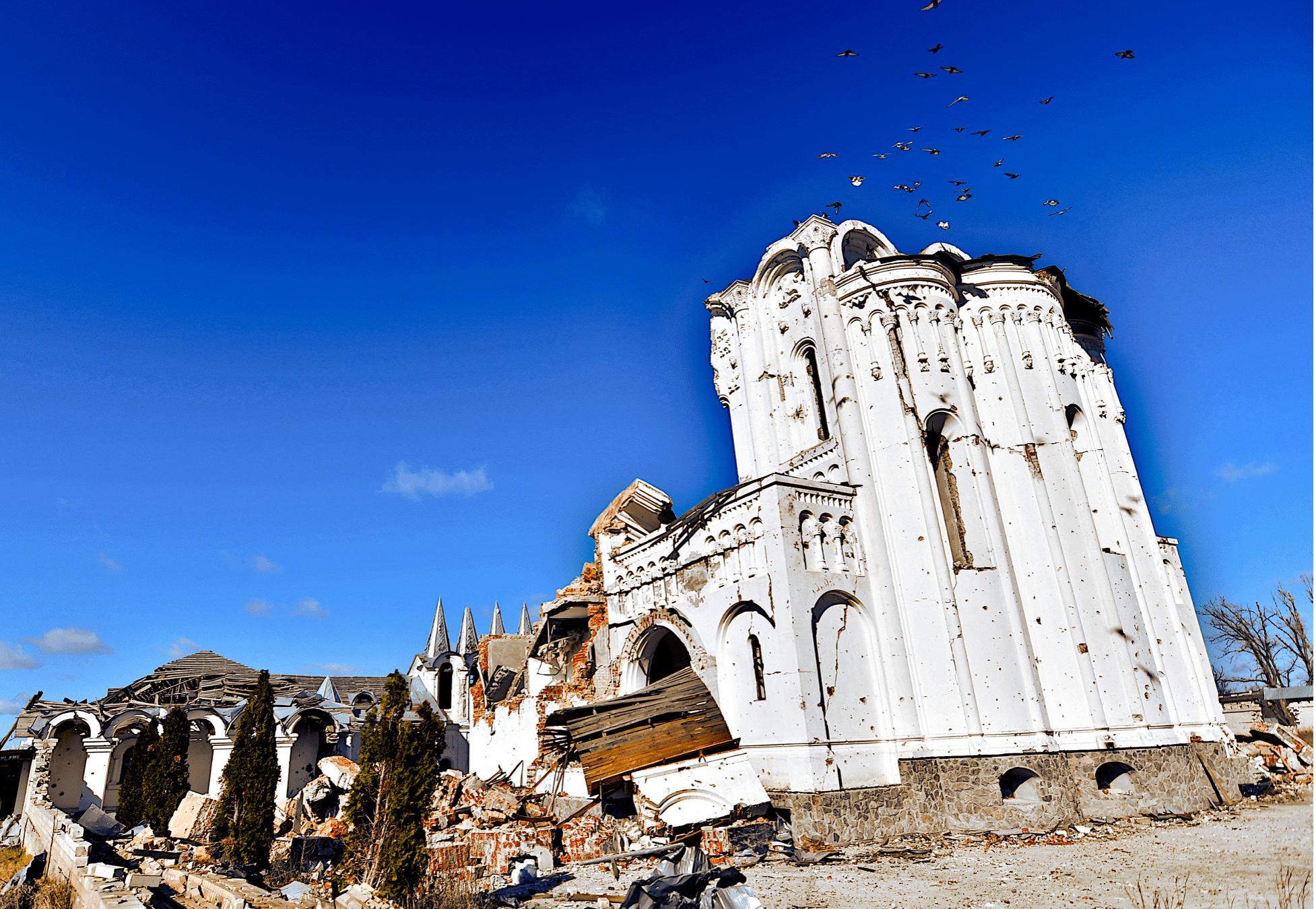

The only movement in Dolyna’s main church came from birds circling nests built in its ruins. There weren’t even stray dogs. A Ukrainian soldier standing watch at a nearby checkpoint told Kyiv Post that no one had lived in villages like Dolyna along the M3 for so long, “a dog can’t find anything to eat.”

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Birds flying above the ruins of the Svyato-Heorhivsky Skyt (hermitage) in Dolyna. March 3 photograph by Stefan Korshak

The war and unlucky geography had flattened the humble Donbas village, and odds are it will be years before anyone will even attempt to fix it. The same goes for hundreds of hamlets, towns and cities devastated by shelling and bombing for 12 months along a fighting line 1,500 kilometers long.

Roadside scene in the village Dolina, destroyed in April 2022 fighting. Practically every building along the M3 highway in a 20-km section that saw heavy fighting was destroyed. March 3 image by Phil Ittner.

Roadside scene in the village Dolina, destroyed in April 2022 fighting. Practically every building along the M3 highway in a 20-km section that saw heavy fighting was destroyed. March 3 image by Phil Ittner.

A subsistence farming community on the northern edge of the Donetsk region, Dolyna had the misfortune of lying on the M3 highway, squarely in the path of Russia’s First Guards Tank Army, which, having spent a bloody month fighting its way through the city of Izyum to the north, got orders in April 2022 to break through Ukrainian lines around the village.

This building was destroyed in April 2022 fighting in northern Donetsk region. March 3 image by Phil Ittner.

This building was destroyed in April 2022 fighting in northern Donetsk region. March 3 image by Phil Ittner.

'Media Is a Front Line' - Volodymyr Klitschko and Others About the Web Summit in Lisbon

Over the next three weeks Ukrainian formations led by the 95th Air Assault Brigade held positions under Russian howitzer, tank, rocket artillery and mortar barrages day and night. Most of the buildings in Dolyna were single-family homes. All were wrecked, most were leveled, and the few hundred residents remaining in the village fled.

On April 18 a massive Russian strike reduced the Svyato-Heorhivsky Hermitage – an annex of the Svyatohirsky Lavra monastery some 15 kilometers away – to rubble. The Orthodox church with meter-thick walls was arguably Dolyna’s only famous structure.ʼ

The men and women of the 95th held, and eventually the Russians fell back. But nearly a year later it appears as if no repairs of any kind had even been attempted anywhere in Dolyna. The hermitage and village were abandoned.

Caption for below: Battalion battle flag flies on a roadside in Ukraine’s Donetsk region near the village of Dolyna, where fighters from the 95th Air Assault Brigade stopped a major Russian offensive in April 2022. Nearly one year later practically all buildings nearby are still completely destroyed. March 3, photograph by Phil Ittner.

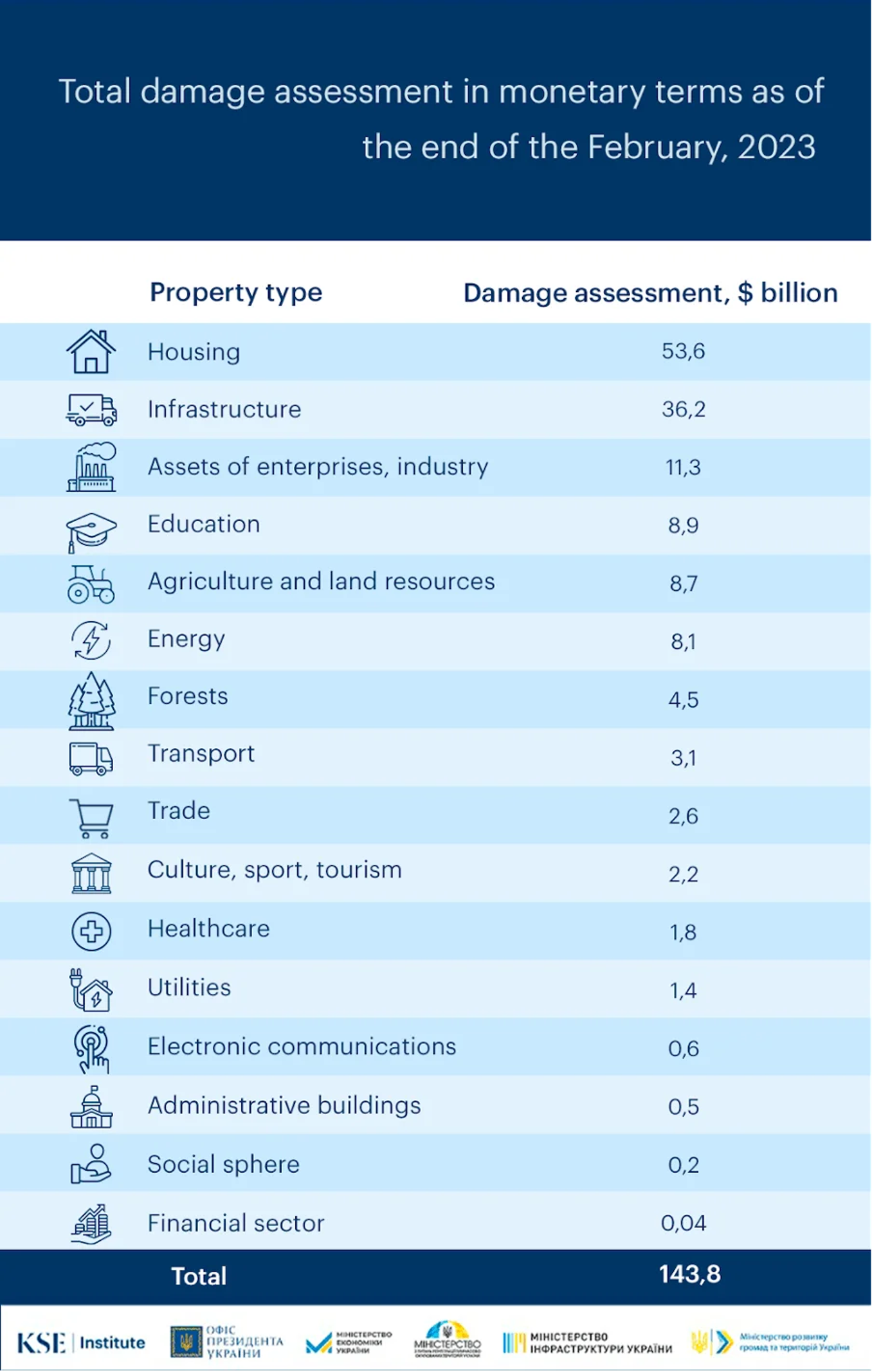

The Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) in a March 23 report estimated the total cost of material damage caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion and 12 months of heavy fighting in Ukraine at $143.8 billion, a sum roughly equivalent to the damage suffered by Syrian businesses and homeowners from all war-related causes over the past decade, or the total destruction and damage delivered by the 2007 American killer hurricane Harvey.

Caption: Graphic published by Kyiv School of Economics in March 23 report.

The report said over 150,000 residential buildings, high-rise apartments, and dormitories – worth $53.6 billion – have been damaged or destroyed, whereas Ukraine’s infrastructure sector has been the second hardest hit, with damage currently estimated at $36.2 billion.

More than 25,000 kilometers of roads, as well as 344 bridges and overpasses, were destroyed or damaged. In February 2023 alone – a month of relatively moderate fighting – Russian bombs, artillery shells, mortar rounds, tank cannon and infantry weapons demolished another $6 billion in Ukrainian property, KSE estimated.

Ukraine’s cash-strapped government is doing what it can to fix critical infrastructure, but realistically, with parts of it under active Russian attack – particularly the national power grid – places like Dolyna will have to wait for the war’s end, because only massive foreign assistance combined with intense mobilization of domestic business can even begin to repair the damage Russia has caused, officials said.

“For the most part, Ukrainian businesses and enterprises [able to assist in reconstruction] have adapted to work during the war, but most are still working to survive,” said Olena Shulyak, a Servant of the People party member heading its Committee on the Organization of State Power, Local Self-Government, Regional Development and Urban Planning, in comment to Kyiv Post.

Single family home in Ukraine’s Kharkiv region destroyed in fighting in October-September. Jan 15 image by Phil Ittner.

Kyiv’s aspiration, she said, is that 60 percent of all reconstruction work be performed by local companies. Therefore, it is now necessary to analyze what materials are needed for the full reconstruction of the country, as well as to determine where the share of imports can be reduced. For example, there is no glass production in Ukraine, so it is worth providing favorable conditions so that manufacturers have the opportunity to enter the Ukrainian market without hindrance. Also, electrical equipment, rubber coating, and elevators are not produced in Ukraine. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the possibilities of launching such productions.

"As for other materials, a lot of them will be needed in the context of reconstruction. In particular, in Ukraine, fittings, bricks, concrete, crushed stone, asphalt concrete, paint, cable, ceramic tiles, etc. are produced. Therefore, the government should protect domestic manufacturers, and introduce programs to revive entrepreneurial activity. In particular, this can and should apply to the preferential lending system for businesses," Shulyak added.

Vyacheslav Olchansky, a construction company owner in the city of Kramatorsk, told Kyiv Post in a March interview that businessmen like him see the obvious long-term opportunity of being in the building business in a country the Russian Federation attacked, but the problem is that interest rates are too high and local capacity to pay is too low, and supply chains are stopped.

So even if “it’s obvious” that demand would be theoretically bottomless for whatever a new window production line setting up shop in Kramatorsk might produce, between needing to pay off 20 to 30 percent annual interest on a business loan, and the cost of sourcing glass panes from Poland and Turkey, “there’s no way I can go into the window business right now and make money,” he said.

Olchansky and other Kramatorsk construction businessmen agree with Shulyak that by far the most efficient way to repair all the damage the Russians have done, would be give their firms access to low interest loans and, equally, establish credit for tens of thousands of skilled construction industry workers – many currently serving in the army – to set up their own companies once the war is over.

Dmytro Petrovych, owner of a small furniture factory, said that his business, the most profitable part of which was selling bulk to wholesalers in Los Angeles, tanked as a direct result of the war, because all but one of his line workers joined the military, and the Russians blockaded Ukraine’s sea ports. Peace would make restarting that business possible, and “someone is going to have to put furniture in all those destroyed homes,” he said. “But unless Ukrainian buyers get credit there’s no way I can sell our furniture and make a profit.”

Whitney Tilson, a New York-based private investor with years of experience in Ukrainian business, said: “In my opinion 99 percent of international capital will never come to Ukraine before the shooting stops. But of course everyone understands the ones that get in early will stand to make a lot of money. If you take iron ore as an example, right now it’s probably possible to buy Ukrainian iron ore at five or ten cents on the dollar. But no one is going to take that deal right now because no one is going to try and do business in an active war zone.”

Tilson predicted the first substantial step of Ukraine’s reconstruction will be an international assistance effort similar to the U.S. Marshall Plan for war-devastated Europe in the 1940s, and that most of that money will go towards overhauling Ukraine’s shattered transportation and energy infrastructure. Repair to private homes and businesses – by a wide margin the part of Ukraine that’s suffered the most damage from the Russian invasion – will come later and most likely be driven by private foreign capital and Ukrainian entrepreneurs, he added.

“Business will wait until they see a situation where they can make money,” Tilson continued. “I think we will see a peace deal in a year and after that you will see a flood of [foreign assistance] capital move into Ukraine, and that will be followed quickly by the private sector. The scale could be enormous.”

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter