The term “Hidden Killers” was first adopted by the U.S. State Department in its 1994 review of the global landmine problem – it was not only a catchy title, but it proved an accurate summary of the ERW problems that had been left behind by the huge number of low-intensity conflicts that followed WWII.

This focused the attention of international communities and organizations on providing the levels of support needed to assist most nations in dealing with this scourge. Sadly, in the following 30 years wars have continued and new ERW has appeared faster than we have been able to clear them.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

This is particularly true in Ukraine, where Russia’s invasion is closer to “general war” than the majority of conflicts that preceded it and the level of ERW contamination is of an order of magnitude not seen since WWII.

In previous articles, the Kyiv Post provided a conservative assessment of the size of the problem and an overview of how to tackle the threat that will face the Ukrainian people from the landmines and other ERW that now litter the country. It will take decades and billions of dollars to deal with these issues.

The key to successfully solving the ERW problem is the creation of the necessary management structures and the introduction of appropriate mine action standards. Kyiv must fully understand the ERW clearance processes and thereby protect its population and territory.

Luxury Western Goods Line Russian Stores, Three Years Into Sanctions

Is Ukraine ready to manage “mine action”?

Management is defined as the processes of planning, decision-making, organizing, leading, motivating and controlling the human, technical, financial, physical, and information resources of a nation to reach its goals efficiently and effectively.

These requirements are particularly true in the case of mine action as the tasks needed to successfully remove the ERW threat are complex, multi-faceted, interdependent, costly, technically challenging and pose an elevated level of physical risk to those engaged in carrying it out.

Is Ukraine in a position to manage the process?

Prior to the 2014 invasion, the majority of ERW clearance or mine action undertaken in Ukraine was limited to making areas contaminated with legacy WWII ERW safe, clearing former “polygons” (military training areas), and removing unexploded ordnance (UXO) resulting from ammunition depot accidents - such as those which occurred in Novobohdanivka in May 2007 and Artemovsk (Bakhmut) in October 2011.

Additionally, a number of military personnel had served in Afghanistan as Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) operators, dealing with Taliban improvised explosive devices and other ERW. These would form the nucleus of Ukraine’s mine action bodies, although they have little experience in managing programs of the size and complexity that will face the country after the war with Russia.

In its autumn 2022 report, the Norwegian-sponsored “Mine Action Review” commented on Ukraine’s preparedness to tackle the ERW problem – its conclusions were that there is much to do.

In the past, Ukraine has tried to develop the organization necessary to manage the mine action process, with mixed success.

In December 2018, Ukraine adopted a new Law for Mine Action in Ukraine, which was supposed to establish an institutional structure for “mine action.” This was supposed to include a National Mine Action Authority (NMAA), under the chairmanship of the Minister of Defense, as well as procedures for accreditation of mine action actors in Ukraine.

However, Ukraine did not implement the Law as “it was inconsistent with a number of other legal acts.” None of the institutions was created and the national mine action response in Ukraine has remained uncoordinated ever since, in spite of a Cabinet of Ministers Resolution in November 2021 to create the delayed and long-awaited NMAA – this was in the early stages of development when Russia invaded and has not really progressed since then.

In December 2020 Ukraine created two mine action centers:

· A national mine action center (NMAC) chaired by the Ministry of Defense (MoD) managed by the State Special Transport Services (SSTS) located near Chernihiv;

· A humanitarian demining center (HDC) under the Ministry of Interior (MoI) managed by State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU) located in Merefa.

The decision to create two mine action centers as opposed to one was a compromise after competition between the MoD and MoI on who should take the lead on mine action. While some feel that splitting responsibilities this way is likely to create problems of control and coordination, it can be argued that the geographical extent and sheer quantity of ERW contamination will benefit from having both ministries focusing on the task, if the split in responsibility is made on a territorial basis.

It is fundamentally vital that a capable management structure be put in place before post-conflict mine action starts in earnest.

Experience tells us that, in the early days of a mine action program, if a control mechanism is not in place, then organizations, many of which will come with their own initial donor funding, will flood in and start to “do their own thing.” To some extent, this is already happening.

In particular, Ukraine will need to establish and enforce mine action standards, for all players whether national or international, that meet Ukraine’s technical requirements and adequately deal with the ERW threats that exist.

Mine Action Standards

The UN-sponsored International Mine Action Standards (IMAS), which have been developed over more than 20 years are fundamental to safe and effective operations and must be applied, not only to national assets but also those employed by international organizations and NGOs who wish to be involved.

There is now a total of over 70 separate IMAS and supporting Technical Notes documents that detail best practices for every conceivable aspect of “mine action.” The documents are constantly reviewed, updated and added to as new threats or techniques are identified. The key standards have been translated into Arabic, Armenian, Chinese, French, Russian, Persian and Spanish – a reflection of the languages used in the most mine-affected nations.

IMAS are designed to be the basis for each country’s own national mine action standards NMAS) to apply to its own “mine action” activity. This is currently assessed to be a problem in Ukraine.

While “on paper” NMAS were finalized by the MoD in September 2018 after multi-year input, outside consultation with GICHD and others, and review from key stakeholders. However, the “Mine Action Review” reported feedback from users in Ukraine that indicated the NMAS did not consider all their inputs and they have not been updated regularly to address new challenges and implementation of what was now considered best practice.

In January 2022, the MoD said it was reviewing NMAS but, in the absence of external technical support, it was unlikely to publish the necessary amendments before April 2023 and the invasion is likely to push this even further into the future.

| LIST OF IMAS DOCUMENTS | |

| 01.10 Guide for the application of IMAS | 02.10 Guide for the establishment of a mine action programme |

| 03.10 Guide to procurement of mine action equipment | 03.20 Procurement process |

| 03.30 Guide to the research of mine action technology | 03.40 Test and evaluation of mine action equipment |

| 04.10 Glossary of mine action terms and definitions | 05.10 Information management in mine action |

| 06.10 Management of training | 07.10 Guidelines for the management of land release |

| 07.11 Land Release | 07.12 Quality Management in mine action |

| 07.13 Environmental management in mine action | 07.14 Risk management in mine action |

| 07.20 Guide for the management of mine action contracts | 07.30 Accreditation of mine action organizations |

| 07.31 Accreditation and testing of animal detection systems | 07.40 Monitoring of mine action organizations |

| 07.42 Monitoring of stockpile destruction | 07.50 Management of human remains in mine action |

| 08.10 Non-technical survey | 08.20 Technical survey |

| 08.30 Post-clearance documentation | 08.40 Marking of explosive ordnance hazards |

| 09.10 Clearance requirements | 09.11 Battle area clearance |

| 09.12 EOD clearance of ammunition storage area explosions | 09.12 EOD clearance of ammunition storage area explosions |

| 09.30 EOD clearance of ammunition | 09.31 IED disposal |

| 09.40 Animal detection systems – principles and guidelines | 09.41 Operational procedures for animal detection systems |

| 09.44 Guide to occupational health and general dog care | 09.50 Mechanical demining |

| 09.60 Underwater survey and EOD clearance | 10.10 Safety and operational health general principles |

| 10.40 Medical support to demining operations | 10.50 Storage, transportation and handling of explosives |

| 10.60 Reporting & investigation of demining incidents | 11.10 Guide for destruction of stockpiled APL |

| 11.20 Open burning and open detonation (OBOD) operations | 11.30 National planning guidelines for stockpile destruction |

| 12.10 Explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) | 13.10 Victim assistance in mine action |

| TECHNICAL NOTES – Issued as supplements to IMAS | |

| 09.10/01 PROM 1 — metal detector warning | 08.20/01 PMN 3 Anti-personnel Mine — technical description |

| 07/05 Metal Detectors - Part 1 | 07.11/01 Land Release Symbology |

| 07.11/02 KPI for Land Release and Stockpile Destruction | 07.11/03 All Reasonable Effort |

| 07.14/01 Residual Risk Management | 07.30/01 Accreditation of Mine Action Orgs — applications |

| 07.31/01 Setting of Animal Detection Systems Testing Sites | 07.31/02 Competencies of animal detection systems handlers |

| 09.30/01/22 Conventional EOD Competency Standards | 09.30/01 EOD Clearance of Armoured Fighting Vehicles |

| 09.30/02 Clearance of Depleted Uranium Hazards | 09.30/03 Guidance on liquid propellant fuelled systems |

| 09.30/04 Fuel Air Explosive (FAE) systems | 09.30/05 YM-1(B) anti-personnel mine - Technical Description |

| 09.30/05 YM-1(B) anti-personnel mine - Technical Description | 09.30/06 Clearance of Cluster Munitions (Lebanon) |

| 09.31/01/19 IEDD Competency Standards | 09.31/01/19 IEDD Competency Standards |

| 09.50/01 Use of commercial tractors for mechanical clearance | 09.50/01/09 Machines |

| 10.10/02 Safety Notes – General | 10.10/03 Explosive Hazard Risk Assessment Rubble Removal |

| 10.20/01 Estimation of Explosion Danger Areas | 10.20/02/09 Field Risk Assessment (FRA) |

| 10.40/01 Medical Support | 12.10/01 Risk Education for Improvised Explosive Devices |

Information Management and Reporting

The Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) is a software suite designed to provide decision support tools that enable monitoring and reporting for a mine action program. It includes a database engine and a geographic information system (GIS) which allows information to be overlaid on maps.

Ukraine has been using IMSMA databases for some time. In 2021, the IMSMA database was housed on two separate servers, one owned by SESU and the other by the MoD. The servers were subject to cyberattacks shortly before the Russian military offensive in 2022, which meant that large amounts of base data needed to be re-established.

GICHD provided support to establish Ukraine’s IMSMA database to become “cloud-based” so that, since April 2022, Ukraine’s IMSMA system now meets the IMAS requirements and is functional.

Incident reports, technical surveys and other operational activity can now be input. Since October 2022 IMSMA has been used to collect data from a variety of sources and GICHD has continued to assist SESU and the MOD in re-establishing their respective IMSMA databases.

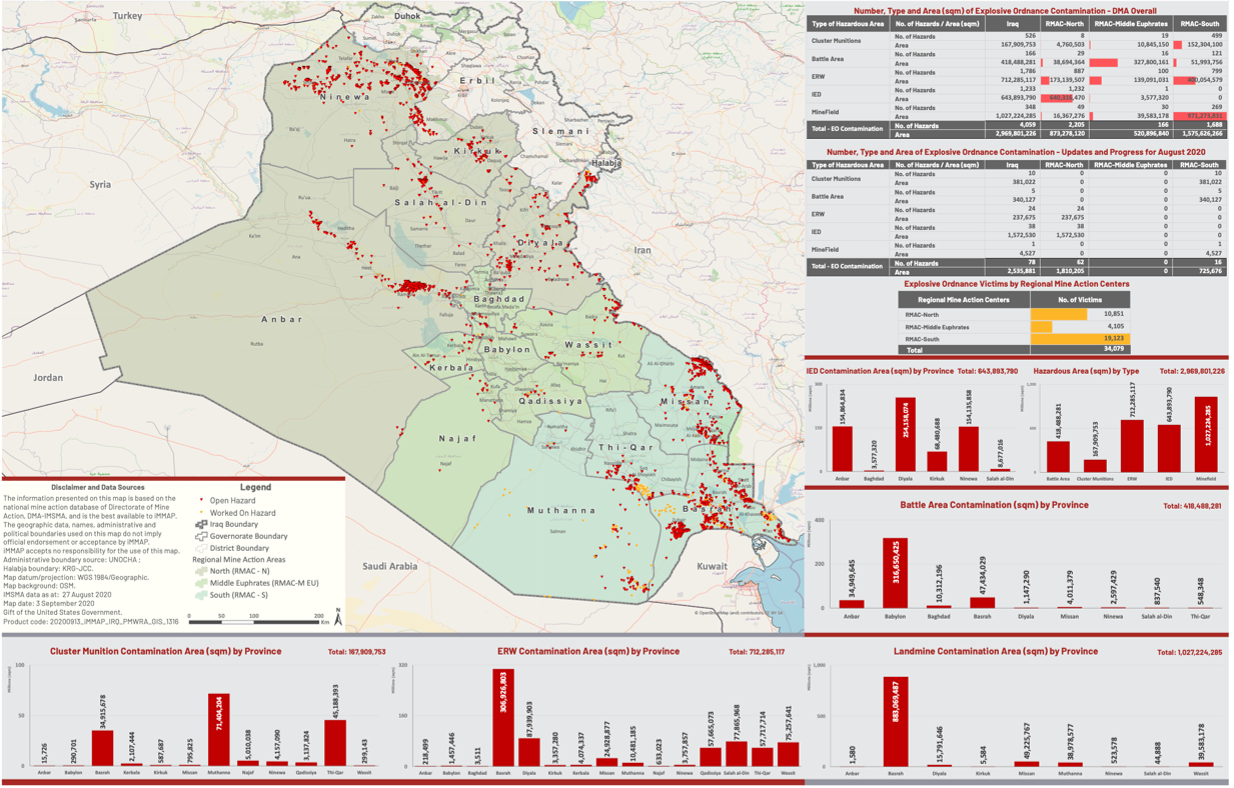

Example of IMSMA Data – (Iraq 2020)Credit: IMMAP.org

Example of IMSMA Data – (Iraq 2020)Credit: IMMAP.org

The ERW Problem – Who Can Help?

In its March 18 article “Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War in Ukraine Will Take Decades to Clear,” the Kyiv Post reported that experts assessed that it could take 50 years or more to remove the explosive ordnance - with costs that run into tens of billions of dollars.

The financial, technical and operational resources needed are so vast that they are certainly beyond the capabilities of Ukraine or indeed any other single nation. So, where and to whom can Ukraine look, to receive the support it will need?

Donors

A total of 37 nations have provided financial, budget support, emergency, humanitarian and military assistance to Ukraine in the amount of around $140 billion, according to the Statista web-site.

This includes about $47 billion in direct military aid from the U.S. and $55 billion from the EU, its Member States and European financial institutions. These figures do not include military aid given as equipment donations, for which ten other nations have contributed.

These statistics are impressive but, of course, the big question is: will these levels of generosity continue beyond the end of hostilities? We have to bear in mind that even these huge figures will pale into insignificance compared to the costs of rebuilding this ravaged nation.

The international reconstruction conference for Ukraine, held in Berlin in October, estimated that reconstruction costs could amount to anywhere between $ 350 and $750 billion, with the bill for demining alone representing 10% - 15% of that figure.

Funding for demining

At the end of World War II, in a situation analogous to what Ukraine will face, an estimated 50,000 German POWs were forced to clear minefields and unexploded ordnance in France, Denmark and Norway, between 1945 and 1948, of which around 3,000 died.

In the period between then and the 1990 invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent first Gulf War, demining had been a “cottage industry,” with affected nations having to rely on themselves to clear any ERW threat.

In Kuwait, the oil-rich emirate funded the mobilization of commercial companies to clear well over two million mines and UXO items. This, along with the U.S. State Department 1994 position paper “Hidden Killers: The Global Landmine Crisis” and the 1997 International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) acted to focus international efforts on the need to support those ERW-blighted nations that did not have the resources to deal with it themselves. These events served to mobilize international opinion to provide funds that really kick-started the new “mine clearance” industry.

The Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor reported that between 2011 and 2020, the last year that figures are available, donors have provided an average of $520 million per year for mine action, of which approximately 70% was spent on clearance.

The monitor also identified, within those figures, the 15 largest donors which were: the U.S., the EU, Germany, Japan, Norway, the U.K., Switzerland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and Italy.

As most of these have advocated and supported Ukraine in its war with Russia, we can anticipate that they will step forward again to help the future demining effort.

Mine action organizations

James Madison University in Virginia hosts the Center for International Stabilization & Recovery (CISR), which reports on all things demining and is regularly consulted and referred to by politicians, academics, donors and the demining community.

Its Global Mine Action Registry currently lists 954 government, military, commercial, NGO and financial bodies that provide mine action related services. These providers range from small nationally-focused groups specializing in “niche” activities, international equipment manufacturers and transnational organizations providing the full range of mine action activities.

A number of these organizations are already here, having been active in supporting Ukraine since the 2014 invasion. These include:

· The Danish Refugee Council (DRC) - formally the Danish Demining Group (DDG)

· Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD)

· The HALO Trust

· Humanity and Inclusion (HI) – formally Handicap International

· Mines Advisory Group (MAG)

· Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA)

· The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

· Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD)

· Mine Action Sub-cluster chaired by United Nations Development Program (UNDP)

The support these organizations have provided practical support in all areas of “mine action,” to a greater or lesser extent. In particular, they have supported Ukraine in its attempts at mine action institutional development with, sadly, mixed success but efforts continue.

What is certain is, that once the war is over, Ukraine will become a magnet for anyone who thinks they have something to offer. While many of these will be legitimate, technically capable and positively motivated there will also be “chancers” who will see an opportunity to make a quick buck. This is why it is vital that Ukraine develops and installs a robust management structure and enforceable standards to deal with the problems.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter