Historical Background – Survival in an Oppressive Context

For generations, the Christian Church in Ukraine has been essential in preserving Ukrainian culture, language, and identity. Prior to Ukraine’s independence in 1991, this country was controlled by foreign powers. When Ukraine was under foreign rule until 1991, many of these empires attempted to diminish or eliminate Ukrainian language and culture.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

From the 1600s to the 1930s, western Ukraine was ruled by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire and then Poland. Meanwhile, the Russian Empire controlled southern and eastern Ukraine from the late 1600s to 1917. The Soviet Union then ruled much of Ukraine from the 1920s and from 1945 onwards all of it until 1991.

During this period, lasting more than three centuries, foreign rulers sought to force their language, culture, and traditions upon the people of Ukraine. For example, under Russian rule, Ukrainians were forced to learn Russian. Ukrainians who adopted the Russian language found opportunities for advancement in society. Those who did not adapt were marginalized by the Russians, who considered Ukrainian a peasant language. Furthermore, those who disobeyed the Russian state were imprisoned or persecuted by the Russians. Others were sent to Siberia or forcibly exiled to another part of the Russian Empire to spread fear within the Ukrainian community.

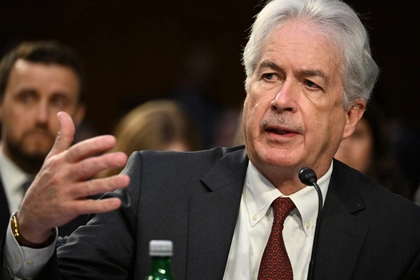

Zelensky Meets CIA Director William Burns in Ukraine

Various Russian rulers also implemented prohibitions on the Ukrainian language. This included preventing texts from being printed in Ukrainian, prohibiting Ukrainians from using their language in day-to-day activities, and forcing Ukrainians to learn Russian in school. These practices were continued intermittently during the period of the Soviet Union.

Beyond language, the Russians have sought to curtail Ukrainian religious and cultural traditions, as well as force their own traditions, narratives and identity on the Ukrainians.

History of Christianity in Ukraine

The Orthodox Church in Ukraine was established during the medieval period of Kyivan Rus. Legend has it that in 988 Prince Volodymyr, enamored with the splendor of Christianity in Constantinople, organized a mass baptism in Kyiv on the banks of the Dnipro River.

The reality, however, was probably more complex and pragmatic. Unifying the overwhelmingly pagan population under the umbrella of a religion that had already spread over most of Europe was, in Volodymyr’s eyes, an astute political move.

In 1240 the Mongols razed Kyiv to the ground, save for the stone churches and monasteries, such as St. Sophia, St Michael’s Gold-domed Monastery and the Holy Dormition Church in the Kyiv Cave Monastery, or Pechersk Lavra. With the capital of Rus effectively destroyed, both political and ecclesial power had to look for support from more powerful neighbors. The Kyivan Orthodox Church was in disarray, with some elements moving to Vladimir-Suzdal (near today’s Moscow), others to Halych (near today’s Lviv).

Subsequently Lithuania, the great power in the 14th and 15th centuries, held sway over Kyiv, although the latter’s church was nominally ruled from Constantinople. After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Moscow declared itself the heir to Kyiv’s church, despite the fact that it did not yet physically control Kyiv. During the following century Kyiv came under the control of Roman Catholic Poland.

Attempts were made at the end of the 15th century, through the Council of Florence, to unify the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, which had excommunicated each other in the Schism of 1054.

With the rise of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Roman Catholic Church progressively established a foothold in the Ukrainian territories it controlled. The 1596 Union of Brest led to the creation of the Uniate Church – today known as the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), whose memebers were allowed to retain much of their Orthodox features in return for loyalty to Rome - married clergy, the Orthodox rite, and not having to use Latin.

But not all Ukrainians were happy with this arrangement. In fact, most of the Cossacks, who had long been chafing under the dominion of the Polish crown, considered it a betrayal and form of collaboration with Catholic Poland. In the first half of the 17th century they and their co-religionist brethren founded an Orthodox proto-university in Kyiv known as the Mohyla Academy.

In 1654, after six years of war with Poland, Ukrainian Cossack leader or Hetman, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, signed the Pereyaslav Treaty, a loose alliance with the Orthodox Muscovite Tsar, which quickly turned into a yoke that would lead to centuries of ‘Russian ‘domination.

In 1686, under Muscovite Tsar Peter the Great, the ecclesial metropolinate of Kyiv was transferred to Moscow and the Orthodox Church in Kyiv was fully absorbed by the Moscow Patriarchate. To this day the canonicity of this enforced transfer is contested by the Patriarchate of Constantinople and Ukrainian Orthodox.

As the UGCC established itself in western Ukraine under the more liberal conditions under Austrian rule, the remainder of the Orthodox Church engaged with the Moscow Patriarchy. There was no choice.

Following the Russian Orthodox Church’s absorption of the Kyiv metropolinate, liturgies in the Orthodox Church in Ukraine were conducted in Russian. In some areas, the Russian rulers abolished the Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Despite these Russian attempts to Russify and dominate, the Ukrainian language survived. As did the desire to recreate an autocephalous – self-governing – Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UAPTS) free from Moscow’s control and reaffirming the cultural patrimony of Kyivan Rus. This occurred during the inter-war period in parts of western Ukraine under Polish rule, particularly Volhynia, though the majority of Ukrainian Christians in Western Ukriane were Ukrainian Catholics.

In Soviet-rule Ukraine, the UAPTs was tolerated for some years during the 1920s and, under its metropolitan, Vasyl Lypkivsky, quickly began to enjoy widespread support, achieving an estimated six million adherents. Understandably, it became a primary target for the Stalinist regime once it hardened it policies in the prelude to the Holodomor and mass purges in Ukraine in the 1930s. Attempts to revive the UAPTs were made a decade later during the shortlived Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1944.

After driving out the German invaders and establishing control over Western Ukraine, the Soviets banned the Ukrainian Catholic Church there in 1946 and drove millions of its adherents underground into a veritable catacomb church. The numerous financially lucrative Catholic parishes and churches in the region were handed over to the Russian Orthodox Church.

This situation of total religious, read politico-national, intolerance towards Ukrainian Christians, both Orthodox and Catholic, continued until collapse of the Soviet system. When Ukraine was able to gradually reaffirm its independence in years 1989 to 1991, not only was the Ukrainian Church legalized, but the UAPTs once again reemerged to challenge Moscow’s imposed domination.

Since independence

Having successfully preserved the Ukrainian language and identity after hundreds of years of foreign rule, Ukrainians immediately attempted to break away not only from Russian political domination but also from the Kremlin’sresidual key auxiliary, now that the Communist party had disintegrated, in promoting its influence abroad – the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC).

A newly constituted Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC) wanting to reatore a Kiyevan Patriarcahte competed for the next three decades with the Orthodox Church which remained loyal to Moscow. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Catholic Church was able to reassert itself in western Ukraine. But the ROC not only retaineden control of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra and the famed Pochaiv Lavra in Western Ukraine, butalso continued to promote a pro-Russian narrative albeit claiming to be autonomous from Moscow.

In 2019, on the eve of presidential elections in Ukraine, the cause of the UOC was belatedly but decisively taken up by the incumbent president, Petro Poroshenko. He managed to persuade the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople to accept the UOC, now united with the traditionally more nationalistic UAPTs, under his jurisdiction by granting it canonical recognition (Tomos) and thereby freeing it from the Moscow Patriarch’s claimed control.

This move, coming five years after Russia had seized Crimea and occupied parts of Ukraine’s Donbas, further underlined Ukraine’s independence and desire to distance itself from Russia and its imperialist ambitions. The Kremlin was visibly angered and by the steps taken by Poroshenko’s successor, Volodymyr Zelensky, to close down pro-Russian media in Ukraine.

In February 2022 the situation of the ROC in Ukraine was further placed in question by Russia’s all-out savage assault on the land, culture and identity of the Ukrainians. To date, the ROC in Moscow has condemned neither the actions and behavior of the Russian state nor the atrocities committed by Russian soldiers throughout Ukraine. Instead, it has condoned them and blessed the Kremlin’s war effort.

The current Moscow Patriarch, Kirill, himself said that the sacrifices made by Russian soldiers in Ukraine would “wash away all sins.” Similarly, if Russian troops died in Ukraine, Patriarch Kirill promised their sins would be forgiven.

Since the invasion, nearly 500 Ukrainian churches and religious sites have been destroyed by Russian forces. In addition, Russian forces have deliberately targeted religious leaders in Ukraine. The UN has condemned these acts, stating that the “deliberate destruction and damage of sites, institutions, and objects of cultural, historical, and religious significance in Ukraine must cease.”

Moscow’s invasion and atrocities have forced Ukrainians, from officials to the general public, to reconsider their relationship with Russia as well as what is generally now perceived be its Trojan Horse in Ukraine – the Orthodox hierarchy and clergy that in reality remain loyal to Moscow. Indeed, numerous Ukrainian priests of the UOC-MP itself have condemned the actions of the Russian state. In addition, several clergymen wrote a letter to Patriarch Kirill condemning the war. Their appeals, however, have gone unanswered.

As a result, Ukrainians have sought other avenues to protest the war. For example, many Ukrainian religious figures have defected from the UOC-MP. Their parishes have left with them as well. To date, nearly 2,000 parishes have gone over to the OUC-KP.

Russia’s Orthodox followers in Ukraine were successfully evicted from St. Sophia’s Cathedral when independence was achieved. Today, almost 32 years later, with Russia waging its barbaric war against Ukraine and its identity, most Ukrainian are united in believing that Moscow’s agents and apologists should be evicted from the Ukrainian religious shrines they have clung to all theses year in order to preserve Russia’s influence and its imperialistic narrative that Russians and Ukrainians are the same people.

Thus the latest dramatic developments concerning the expulsion of the pro-Russian Orthodox hierarchy and monks from the Pechersk Lavra.

Ukraine’s representatives stress that there should be no confusion about the current case concerning the restoration of the Pechersk Lavra to the Ukrainian people. This is not about religious freedom or tolerance. For Ukrainians, they emphasize, this a continuation of the unfinished business of decolonization and reassertion of sovereignty, cultural identity and civilizational self-determination, and ultimately – the restoration of justice.

This article draws on elements from a a longer piece submitted by Mark Temnycky that has been adapted to the latest developments.

Mark Temnycky is a freelance journalist covering Eastern Europe and a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. He can be found on Twitter @MTemnycky

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter