The scenery around the factory grounds is gloomy and grim, to say the least, but among the demolished workshops and blasted-out windows covered with plastic wrap, you can hear the laughter of workers between shifts. The dingy shop smells of iron, just like the train cars they repair, but suddenly, the sophisticated scent of French perfume wafts through the air.

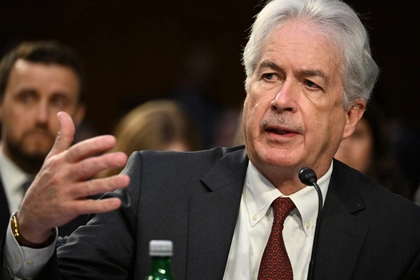

Amidst a huddle of railroad car parts and heavy machinery are two women, Liudmyla Zarutska, the director of the gear shop, and her subordinate, Natalya Barmetova, one of about 40 refugees from war-torn cities and villages around the country now employed by the plant.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Natalya has been working at the company for only a couple of months. Liudmyla has been at the factory for more than 10 years, where she started as a crane operator. She now oversees about 50 people in her shop, evenly divided between men and women, and she worries about their future.

Just like a Ukrainian version of the Soviet classic film, ‘Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears,” Liudmyla has become a motherly icon charged with the well-being of a factory and its family, and perhaps even, a nation.

"There are fewer orders now, and I am most concerned about providing my subordinates with work so they can feed their families," Liudmyla says.

Liudmyla Zarutska, workshop manager at Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant and her employee Natalya Barmetova is a master in the workshop. She is a refugee from the hostilities in the eastern part of Ukraine. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

Moscow Imposes Russian Car Insurance in Occupied Ukraine by 2025

Despite her concerns about invoices, and the ramshackle feel of the factory in general, make no mistake: The resurrection of the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant is a Ukrainian wartime success story. It is a tale of workers who rescued a mission-critical business from the rubble, a model of resilience in the face of a Russian onslaught hell-bent on crippling the Ukrainian economy.

On June 5, 2022, the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant was attacked by five Russian missiles, four of which hit the factory’s industrial facilities. The plant was severely damaged. Immediately after the attack, the management and employees were unsure whether they could resume operations. One of the plant's workshops was so badly destroyed that people have had to operate a broken forge in the open air, even in months when temperatures are well below freezing.

And yet, less than a year later, the company has fully restored its operations.

Employees at a broken forge are working on the open air. Photo credit the administration of the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant.

The plant’s main activities are the repair and construction of the container car fleet for Ukrainian railways, and it employs about 600 people. Before the war, the company planned to increase production, with a forecast of 390 railcars for 2022.

"When the war started, we had to cancel our expansion plans,” says Yuriy Phillipov, the director of the factory. “We were fighting for the survival of the company. When spring came, and the issue of exporting crops arose, we decided that it would be essential to expand production and organize the repair of grain containers.

“As soon as we mastered this production and received the required certificates in May, we were attacked by Russian missiles."

Damaged facilities of the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant. Photo by Aleksandra Klitina.

According to Yuriy, the Russian attack was aimed intentionally at destroying the company's facilities where grain railcars are repaired. Because it is has become basically impossible to export Ukrainian produce via cargo ships, as ports and Black Sea routes have been blocked by Russian forces, the railroad remains the main export corridor, the last major artery of the Ukrainian economy.

"Even before the war, there was a problem with the lack of grain carriers. With their attack, the Russians hoped to undermine Ukraine's export capacity completely,” he says.

The Russians also launched a disinformation campaign afterward, insisting that the goal of the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant missile strike was to target military equipment and weapons.

“We decided to invite journalists to the site to see for themselves,” Yuriy says. “There was still a risk something else might explode, so we quickly fenced off the area as much as possible and drew a map for journalists to follow. We showed them that there was no military equipment here. The briefing was held at 3 PM., and the attack happened at 6 AM. We would not have had time to take anything out.

“We saw the eyes of the people who came after the attack. They were ready to say goodbye to the plant. People reacted with fear. There were rumors that the plant was finished. We grieved for one day, and then we started to rebuild.

“It was a challenge for us. At first, we had to clear the rubble to understand where we were, what we could save, and what was destroyed. We were able to remove some equipment and repair it. It was unexpected that so many people would respond, including the district administration, the local community, NGOs, and even teachers at nearby schools,” Yuriy says.

At the time of the strike, 24 security guards and energy service workers were on the plant's grounds, and one employee was injured by shrapnel. [As a matter of protocol] all workers go down to the bomb shelter when the alarm sounds, and this rule is strictly observed.”

The bomb shelter is designed for 1,500 employees, including bedding.

“On February 24, we let people from the neighborhood in,” Yuriy continues. “At the peak of the Russian attacks, we had up to 3,500 people in the shelter. The police even came to us to check people's documents because sabotage groups were operating in the city.”

A woman living in the neighborhood helps clear the factory's rubble after the Russian attack – in June. Photo credit the administration of the Darnytsia Railcar Repair Plant

The main buildings on the premises are still covered with plastic wrap, and the director works in a cold office without windows. When asked what the secret to the company's efficiency is, he responds: “The secret is the people.”

The plant managed to bounce back right away, thanks to the help of its employees who brought tools from home in order to work, and from outsiders who responded with kindness. For example, the window wraps were provided by a company that produce these materials nearby.

Employees here have worked here as families, historically, and they took the destruction by the Russians personally. According to plant’s leadership, when workers came with their families to clear the rubble and survey the extensive damages, they said, "My grandfather built this house."

Again, the company employs about 40 refugees from regions where active hostilities are taking place. Three of them work in Liudmyla’ workshop.

“When we were in the bomb shelter during the alarm, one of the refugees told us that when they were evacuated, they had to run with their wives and children over the corpses and body parts of people, because there was no other way out. And he talked about it so calmly,” Liudmyla says.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter