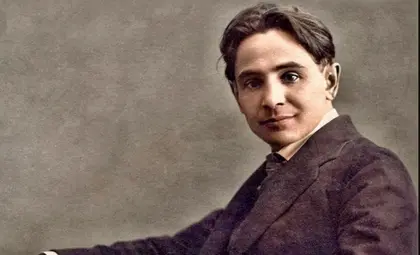

Hnat Khotkevych was the epitome of the polymath, a unique man of genius who was a multilingual writer, translator, engineer, teacher, ethnographer, musician, composer, actor and film director. He designed a diesel-powered locomotive before the Americans; he composed more than 600 musical works; he wrote several plays and founded folk theaters; his poetry was used as lyrics to popular folk songs; he founded the Bandura Choir in Poltava which was the first Soviet collective to tour North America; he wrote several dozen movie scripts and starred in a well-known feature film as a wandering blind minstrel playing the kobza or the bandura. His name is known to all Ukrainians but to very fewothers.

The life story of Hnat Khotkevych reads like a novel. He was born on 12 January 1878 in Kharkiv, where his father was a cook and his mother a housemaid to a merchant who travelled extensively and took Khotkevych and his family with him. On one such trip, the seven-year-old boy met a blind kobzar who taught him to play the bandura but it was only several years later that he was able to afford to buy his own. From then on he took his bandura with him everywhere, even while studying at a public school and the Technological College in Kharkiv. He was a bright and diligent student and got high grades in all subjects, but spent almost all of his spare time with kobzars. They commented that “he plays very well but, if he were blind, he could be great kobzar.”

Sahaidachny: Ukrainian Leader Whose Cossacks Saved Europe From Ottomans

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

This could have been his downfall as he was soon expelled from college and exiled from Kharkiv for two years for mixing with kobzars who were much despised by the authorities. The young man took his bandura and went to Kyiv where he met the famous composer, Mykola Lysenko. Having heard Khotkevych’s repertory, which also included his own works, Lysenko made Khotkevych a soloist in his choir and ensured that he was readmitted to college.

He did well but did not graduate with honors, because of the “political stain” on his academic record. The young graduate was appointed to a modest position in the technical maintenance department of the Kharkiv-Mykolayiv railroad administration. He continued to give every minute of his spare time to music, his first love and where he was to find the love of his life.

Music brought him together the young handsome engineer and Kateryna Rubanovych, the gifted music-loving daughter of a merchant. They got married even though his salary was miserable. However, as his working hours were not long, he had time for his creative hobbies. In 1903 he opened a Ukrainian workers theatre in Kharkiv which, in the first three years, staged more than 50 plays.

In 1905, he was elected as head of a railworkers strike committee which resulted on him being put on a black list by the Russian authorities. He managed to escape arrest and, assisted by other workers and Lesya Ukrainka, the famous poet, he fled to Halychyna (the historical pre-Carpathian area covering the present-day Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk regions), then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The family settled in the village of Kryvorivnia near the Romanian border where, very soon, the fame of his extraordinary musical talent spread throughout the region. He gave concerts in almost every village and town where he later reminisced that he “fell in love with the Hutsuls and their beautiful highlands” from the very moment he arrived.

The beautiful landscapes and those hard-working, open-hearted people inspired him to write the story The Soul of Stone and to create a unique Hutsul folk theater. The illiterate actors learned their roles by ear but played just perfectly on the stage. Maria Zankovetska, the great Ukrainian actress, lavishly praised the theater and even donated all her savings to it.

However, Khotkevych’s family life was anything but a bed of roses. The family was barely able to make ends meet and only survived thanks to a small kitchen garden and odd jobs. The birth of a third child was the last straw that broke the marriage. His frustrated wife left Hnat and their three children in the Carpathian village and went to Moscow to rejoin her parents.

The grass widower was soon comforted by a young married woman, another Kateryna herself a budding writer. When the threat from the authorities passed, Khotkevych and his lover returned to “mainland” Ukraine but, soon afterwards, Kateryna left their newborn baby with him and his mother and returned to Lviv.

Khotkevych settled in Kyiv where he edited a literary magazine and organized countrywide tours of the Hutsul Theater.

Hnat Khotkevych with amateur actors of the Hutsul Theater

When WW I broke out in 1914, the authorities began to persecute him again – this time for his pacifist position. In early 1915, he was exiled to Voronezh, Russia, where he spent almost three years until the 1917 Bolshevik r5evolution and the proclamation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic.

Soon after he returned to Kharkiv, Khotkevych published the first volume of his History of Ukraine, the play Igor’s Campaign, the tetralogy Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the novel Berestechko. He translated Shakespeare and Victor Hugo, organized a village choir and an instrumental ensemble, and taught at a technical college.

In 1921, when he was 43, he became acquainted with a 20-year-old student, Platonyda Skrypko, and shortly thereafter married her.

At the time, Khotkevych was one of the most popular writers in the country and after 10 years of marriage, having received an advance payment for an eight-volume collection of his works, he was finally able to buy a house for his family.

However, Soviet censors found “manifestations of bourgeois nationalism” in an article where he condemned the 1654 treaty between the Ukrainian Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the Moscow Czar Alexei Mikhailovich as the cause of “the enslavement of Ukraine.” In 1932, he was fired from all positions and all his works were banned. The eight-volume collection was removed from bookstores and libraries and the publishing house demanded their fees back. Once again the out-of-favor writer survived by doing odd jobs and selling his personal belongings to survive.

In 1934, Khotkevych was seriously injured in a railroad accident and was unable to work. Eventually he wrote a desperate letter to the president of the Academy of Sciences asking for a pension but he was arrested before being answered. After three months of interrogation and torture, he confessed to “espionage for Germany” and was executed in October, 1938.

His widow was prosecuted as an “enemy of the people” and in 1945, soon after WW II ended, was exiled to Kazakhstan.

In 1956, she was rehabilitated – along with her late husband and hundreds of thousands of other innocent people executed and tortured to death by the Stalin regime. She returned to Ukraine and worked in the Ivan-Franko museum in Kryvorivnia, the village where Khotkevych had spent his six happiest years.

His children went different ways: his youngest daughter Halyna was taken by the Nazis to Germany for slave labor. After WW II, she found herself in Morocco, along with other displaced persons, where she sang in the Church of Resurrection in Rabat. In the early 1970s, she moved to France and married the priest of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in Grenoble, who also came from Kharkiv. Khotkevych’s elder daughter, Olha, settled in Venezuela.

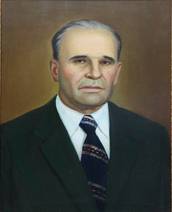

His youngest son, Volodymyr, fought against the Bolshevik troops and was killed in action near Kursk. Another son, Yevhen, drowned while crossing the Iranian border. Only his eldest son, from his first marriage also Volodymyr prevented the family tree from dying. He made a brilliant academic career here in Ukraine and became rector of Kharkiv University.

Volodymyr Khotkevych, rector of Kharkiv University

Hnat Khotkevych lives in the grateful memory of Ukrainians: one of the central streets in Kyiv as well as streets in Kharkiv, Lviv and other cities and a special scholarship of Kharkiv University bear his name. His books have been translated into several languages and are on the Ukrainian literature curricula in schools. His plays are staged in theaters in this country and abroad; and people sing beautiful folk songs, not even knowing that their author is Hnat Khotkevych – a gifted Ukrainian musician, composer, writer, engineer, teacher, ethnographer, actor, and film director.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter