Why the legacy of Kikabidze still lives in every household of the post-Soviet world and why he has not won his war. Not yet. A tribute and some reminiscences from a friend.

Known by his nickname “Buba”, Vakhtang Kikabidze has left a legacy few Soviet celebrities could boast of.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Becoming a name in the Soviet era and known in every household on the post-Soviet terrain, he was one of the few to withdraw entirely from Moscow, never setting foot on Russian soil after the first full-scale Russian war against its Georgian neighbor in 2008.

“If only I were 20 years younger, I’d go to Ukraine to fight. I am a good marksman, by the way,” — Kikabidze used to say.

In one of his last interviews, Kikabidze warned about the Russian aggression that can cause another war in the Caucasus.

“I think he (Putin) will probably go to the Caucasus to “pacify” Armenia and Azerbaijan. That’s when everything we like here in the Caucasus will no longer be there because later, he will attack Georgia. This is clear.” — the legendary actor warned.

He transformed Russian rhetorical narratives about “denazification” of Russia’s neighbors into a farce to the millions who listened to him.

“I grew up in a house where there were 17 different nationalities: Armenians, Georgians, Russians, Kurds, Christians, Zoroastrians, Jews... There was a teacher of foreign literature who was originally French. That’s how I grew up: I thought everyone around was Georgian simply because they spoke the language,” he told me during our first encounter 15 years ago.

Eurotopics: Who Can Ukraine Count on in 2025?

As a child, he was expelled from school for cleaning his shoes with a red tie, which the “pioneers,” a Soviet version of boy scouts, had to wear.

“I had just one pair of shoes, and millions of red ties were around, so what do I choose?” Buba used to say.

A chain-smoker, a joker, a hooligan, he never played by the rules. His uncle was taken to a Soviet camp for refusing a toast to Beria, one of Stalin’s main executioners.

“He poured the wine from his glass, saying, ‘I will not drink to the health of this monster.’ Next night he was taken by the NKVD,” — Buba said, referring to the Soviet spy agency, the FSB predecessor.

Buba came from the noble family of Bagrationi: Georgian tsars and Russian battlefield generals during the Napoleon wars were his distant relatives.

He played a Soviet version of rock’n’roll in a band when there was no rock’n’roll in the whole country officially.

One could not legally buy Elvis or Little Richard records in the USSR: it was prohibited music, part of the “rotten Western” culture.

“First you dance to jazz, and then you sell the fatherland to the yanks,” was a popular saying at the time.

Buba once went abroad with his boys’ band.

Like every artist allowed to travel abroad, he was accompanied by KGB spies. They made one of the KGB spooks blind drunk, undressed him, put some cash on his bare chest and took a compromising picture. In the morning, the spy woke up: “No worries, mate,” Buba told him with a smile, “we will never pass it to anyone. Hope you will not mention our adventures either.”

He had good reason to detest the Soviet system.

Kikabidze remembered the night in 1989 when Russian soldiers attacked a peaceful civilian protest in Tbilisi with trench shovels. For Georgians, “shovel” became a synonym for Russian aggression, attacks on civilians, torture policy, and political murder.

Buba came back home to his wife and son that night.

His son was doing homework in the Russian language. “What is the Georgian word for the shovel, dad?”, his son asked. Kikabidze was so nervous he forgot the word.

“Ask your granny, son. How dare you ask me when the elderly are in the house?”

Buba’s mother was in the kitchen. Everyone knew what had happened in Tbilisi that day.

Everyone was still afraid to talk openly.

“S hovel? In Georgian? Russian ‘shovel’? — the old lady said. — “We are the Bagrationi, son. We don’t have to know that peasant language...” she responded in a firm voice.

Kikabidze was not active in cinema after the collapse of the USSR. However, he remained a famous singer, lately using his public appearances to campaign against the Russian aggression and for a Georgian opposition party called “the National movement.”

“He lived in every household; everywhere there is a bit of his legacy,” says Georgian artist Koba Samkharadze.

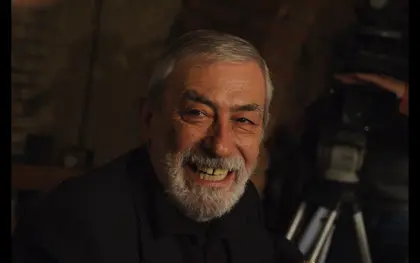

KIkabidze's funeral in Tbilisi on Jan. 19, 2023.

KIkabidze's funeral in Tbilisi on Jan. 19, 2023.

Kikabidze hated Stalin and the legacy of the Empire that had destroyed his family during Soviet rule.

“Putin is sick. He loves Stalin, the one who destroyed half of our intelligentsia,” — Kikabidze used to say.

Kikabidze was campaigned against the incumbent Georgian leadership, which stopped Georgia from directly helping Ukraine during the bloodiest war of this century, the European continent has witnessed.

Doing business with Russia and trying to avoid getting involved — that’s what Kikabidze was angry about, and that’s what he could never be accused of.

The 84-year-old star of “Mimino” and “Don’t grieve” movies was buried today, Jan. 19, in Tbilisi. His long illness had never stopped him from trolling Putin and his clique.

His last will was to be buried covered in Georgian and Ukrainian flags.

A vast crowd took his body to the old cemetery in this mountainous city from an old Kashveti downtown church.

At the gate of this church, Tbilisians were selling t relics of the pre-Bolshevik and Soviet times. Among other items, busts of Stalin.

“We sell them to Russians. Sometimes Iranians buy them’ — one of the merchants told Kyiv Post. — “Preserving the totalitarian legacy? Nothing close to it. There’s nothing bad about squeezing money from them. It’s nothing personal. Strictly business”.

Kikabidze drew a distinction between business and principles and remained an uncompromising patriot, enemy of Russian imperialism and supporter of Ukraine until the very end.

Rest in Peace, dear, unforgettable, friend.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter