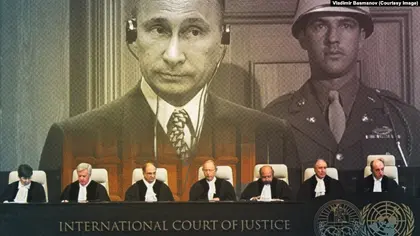

Could Russian President Vladimir Putin one day stand in the dock in The Hague? The prospect seemed to move closer after Germany backed a special court for the invasion of Ukraine.

German Foreign Minister Anna Baerbock called on Monday for a tribunal to get around the fact that the International Criminal Court (ICC) cannot prosecute Russia for the “leadership” crime of aggression.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

But there are major hurdles before any such court could even be created, let alone put Russian leaders on trial.

- Why a special tribunal? -

Germany’s Baerbock said a special tribunal would fill a “severe gap” in international law.

The Hague-based ICC launched an investigation in February into war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine.

It was able to do so because Kyiv accepted its jurisdiction, even though neither Russia nor Ukraine are members of the court, which was set up in 2002.

But while changes to the ICC’s governing Rome Statute gave it powers to prosecute aggression from 2018, it still cannot do so for non-member states.

The only way it can is by a referral by the UN Security Council -- but Russia, with its permanent seat, would automatically veto that.

- What’s the German plan? -

Baerbock proposed a “new format” of court based in The Hague, to be set up in the near future if possible.

The court could “derive its jurisdiction from Ukrainian criminal law” but have international prosecutors and judges and foreign funding, she said.

Poland to Use EU Presidency to Fast-Track Ukraine’s NATO and EU Membership

That would be different to tribunals under international law, such as those for the 1990s wars in the former Yugoslavia.

And while tribunals for Cambodia and Kosovo have used local laws, they were not able to try aggression between one state and another.

At the same time, Baerbock proposed changing the ICC’s rules in the long term so that it can prosecute non-member states for aggression.

- Who would it target? -

A special tribunal would target Russia’s civilian and military leadership for ordering and overseeing the invasion of Ukraine, Baerbock said.

While the ICC could charge Russian soldiers and commanders on the ground, Baerbock said it was “important that the Russian leadership cannot claim immunity.”

Aggression was the “original crime that enabled all the other terrible crimes”.

- What does the ICC think? -

ICC prosecutor Karim Khan, who held talks with Baerbock on Monday, has opposed a special tribunal for Ukraine.

He said in December he should not be “set up to fail” by the creation of a special tribunal and urged the international community to focus on supporting his own investigation.

Baerbock said it was crucial to keep supporting the ICC and insisted that a tribunal would not undermine it.

- What are the hurdles? -

To exist in the first place the court needs international support -- and that could be hard.

Much of the West seems to be on board, with European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen calling for a special court in December and the Netherlands offering to host it.

But the rest of the world would likely be less keen.

“I hear those critics voicing concerns that such a path would show we care about a war because it happens in Europe, and I share that concern, so it’s important that we talk to partners from other regions,” Baerbock acknowledged.

But the biggest problem could be bringing any suspects to justice.

Russia has said any Ukraine tribunal would lack legitimacy, and would refuse to extradite suspects.

Ukraine could extradite captured Russians but that would leave high-level figures unscathed.

“Unless there is a regime change in Russia, Putin and other very high-level leaders would have to leave Russia in order be subject to arrest,” said Cecily Rose, assistant professor of public international law at Leiden University.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter