The internet in the least-populous member of the European Union, Estonia, has one of the highest penetration rates in the world. Moreover, Estonians make much broader use of it than in other countries – they even use it now to elect their parliament, start companies and pay their taxes.

In fact, the huge amount of electronic services created by the Estonian government to ease its citizens’ interaction with the state has turned the country into the world’s leading digital society. These electronic solutions save money, time, and make government operations entirely transparent and open to public scrutiny.

- Check the latest war in ukraine update from the Kyiv Post's news articles released today.

- Examine the most contemporary Ukraine news that came out today.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

The e-services created by the Estonian government under its e-Governance initiative include services such as i-Voting, the e-Tax Board, e-Business, e-Banking, e-Tickets, e-Schools, University via the internet, and the e-Governance Academy – the Estonian organization that aims to educate officials and citizens about the use of the internet in running the country.

Hannes Astok, the director for development and strategy at the e-Governance Academy, says one of the country’s e-services – digital signatures – alone saves Estonia millions of euros.

“We’ve calculated that with every digital signature provided, the country saves at least €1,” Astok told the Kyiv Post. “Since Estonians have provided more than 280 million digital signatures during the last decade, we have saved around €280 million as a nation. No government ever has enough money – there’s always a better use for every penny.”

In total, Estonia saves 2 percent of its gross domestic product through the paperless governance every year, according to Taavi Rõivas, the country’s prime minister.Internet Voting

Internet Voting

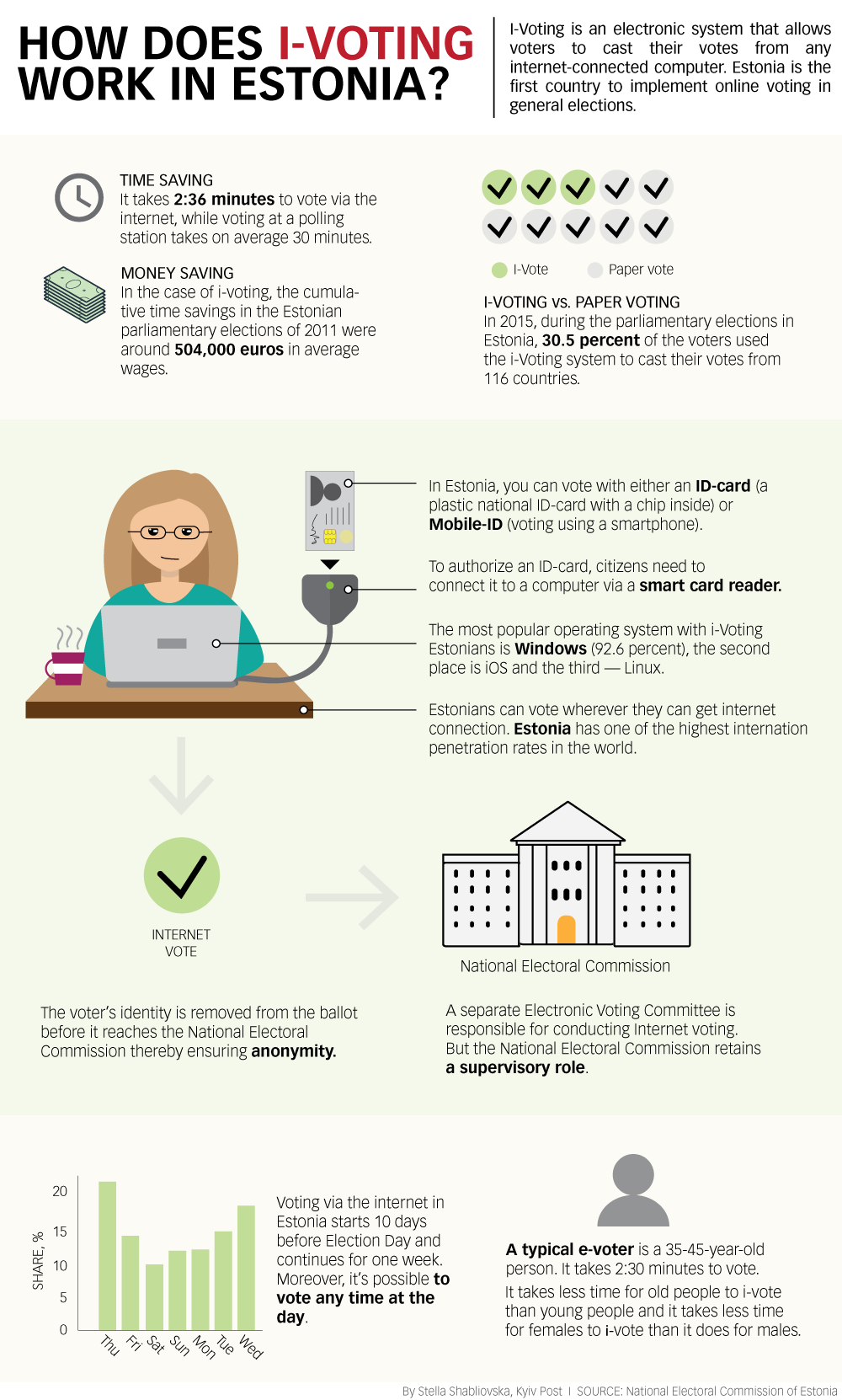

The first internet-integrated vote in the world happened in 2005, when a modest 1.9 percent of Estonia’s 1.3 million population went not to polling stations to cast their votes in municipal elections, but online to vote for their preferred candidate.

In subsequent elections that percentage has gradually increased, with the level of online voting growing to 30.1 percent at the last parliamentary elections, in March 2015.

“If the government asked people to send a paper letter, many people wouldn’t know anymore how to print it out, where to buy an envelope, how many stamps are needed, and where the nearest mailbox is,” Astok said.

Voters identify themselves with either an ID-card – a smart card issued in Estonia by the Ministry of Internal Affairs – or mobile-ID, a service that allows a client to use a mobile phone as a form of secure electronic identification.

Since 2013, Estonians have also been able to check if their votes have reached the election committee server and have been counted.

Although the system allows voters to remain anonymous, every time a vote is cast on the internet, the electoral bodies can see a range of other data about voters. This allows them to gather statistical data about voters’ sex and age, and time a vote was cast, which are analyzed for scientific purposes, according to Kristi Kirsberg, an advisor at Estonia’s National Electoral Committee.

“This provides insight into how voters vote,” Kirsberg said.

Despite winning praise from Estonian election officials, computer security experts from outside the country have warned that any voting system that transmits voted ballots electronically cannot be completely secure.

“(However), the system has been used in eight elections – municipal, national and European – without a single serious incident,” Kirsberg said. “Every aspect of online balloting procedures is fully documented, and the procedures are rigorously audited,” she added.

E-Business

The World Bank placed Estonia 12th in the 2017 Ease of Doing Business ranking. Compare that to France at 29th, and Switzerland at 31st – or Ukraine’s place at 80th.

Many businesspeople run their companies in Estonia on the web, and 98 percent of all financial transactions in the country are now carried out online. And as many as 95 percent of the country’s citizens now file their tax returns online.

The Estonian government now plans to attract even more investors and young entrepreneurs to the country: in December 2014, Estonia became the first country in the world to introduce the concept of electronic residency.

Having obtained an Estonian e-residency, one receives a government-issued smart ID-card that includes a digital identity and authorization code. This allows e-residents to sign important documents digitally and accessing secure services – even if they don’t live in Estonia.

For example, having an e-Residency would allow a Ukrainian entrepreneur to establish an Estonian company that he runs from Singapore to serve clients based in Germany. He would also be able to use his digital signature to sign contracts with customers throughout the European Union.

In other words, one could administer a company from anywhere in the world, conducting e-banking, and paying Estonian taxes (at a flat 20 percent rate).

About 13,000 people have already obtained electronic residencies in Estonia, but its government envisions 10 million virtual residents by 2025.

“E-Residency is just an extension of our existing digital society,” e-Residency managing director Kaspar Korjus told the Kyiv Post, saying that the state accepts almost everyone. “Only 1 percent of people are rejected – if they fail a police background check. The reasons may include previous poor business behavior.”

Ukrainian dream

Estonia’s example could show the way forward for implementing similar electronic systems in Ukraine, according to Dmytro Dubilet, the IT director at PrivatBank and founder of the Ukrainian government’s electronic services portal, iGov.

“But it’s important to understand that Estonia was building its basic systems 15 years ago. Many things have changed since then, especially in terms of technology,” Dubilet told the Kyiv Post.

And the e-Governance Academy’s Astok said it was impossible to entirely copy an e-government solution from one country to another, as legislation, organizational culture and traditions vary.

Nevertheless, work on transferring Estonian e-government know-how to Ukraine started back in 2012, with Estonian advisors helping to set up electronic document management systems, mobile applications, geographical information systems and call centers in Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasts.

Astok said the key elements in e-government are active management and political leadership, along with supporting legislation and technology. The technology is the easiest part, as almost every country has a lot of talented engineers and tech companies, he said.

“But if the government’s willingness to change is missing, it’s unlikely anything will happen,” Astok said. “Government is one of the key players in e-society development in every country. Only together with the government can all other stakeholders – businesses, citizens and NGOs – create a secure and trusted digital society.”

Dubilet agrees, saying that support from the government is very much needed in Ukraine “at least at the organizational level.”

“Luckily, we have it. Without this support, we wouldn’t have achieved anything.”

The Kyiv Post’s IT coverage is sponsored by Beetroot, Ciklum and SoftServe. The content is independent of the donors.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter