For several years after the 2004 Orange Revolution, vibrant political talk shows were a sign of the country’s blossoming democracy.

But almost two years into the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, these shows have plummeted in popularity amid widespread disillusionment with politics and accusations of political bias.

JOIN US ON TELEGRAM

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Before the Orange Revolution that denied Yanukovych his first presidential bid seven years ago, freewheeling debate on televised political talk shows was stifled on tightly controlled airwaves.

Afterwards, politicians from the government and the opposition faced off in lively debates about the key political and economic issues of the day. The shows were broadcast during prime time on Friday evenings and drew impressive audiences.

Experts: top political TV shows suffer from bias, same old faces

Savik Shuster and Yevgeny Kiselyov, two Russian journalists, came to Kyiv to enjoy the freedom to produce their own programs without the tight political control that exists in Moscow.

The shows reflected a new climate of freedom in the country, where a variety of political voices could be heard.

But critics say the presenters’ shows are increasingly toeing the line of Yanukovych and his allies, who have moved to take greater control of the country’s political life, including by pressuring and jailing opposition leaders.

This alleged bias is sometimes subtle, such as leading questions, choice of topic and guests.

It perhaps isn’t surprising, as “Shuster Live” goes out on state-owned First National Channel while “Big Politics with Yevgeny Kiselyov” is broadcast by Inter, owned by Security Service chief Valeriy Khoroshkovsky.

Both Shuster and Kiselyov brushed aside accusations of bias in their shows.

Critics also argue that the programs have gone stale, constantly featuring the same politicians and frequently turning into shouting matches where mudslinging is the main weapon rather than powerful arguments.

“The public is generally disappointed in political talk shows. They have turned into dog-fights where presenters also exploit the topics,” said Natalya Ligachova, head of media watchdog Telekrytyka.

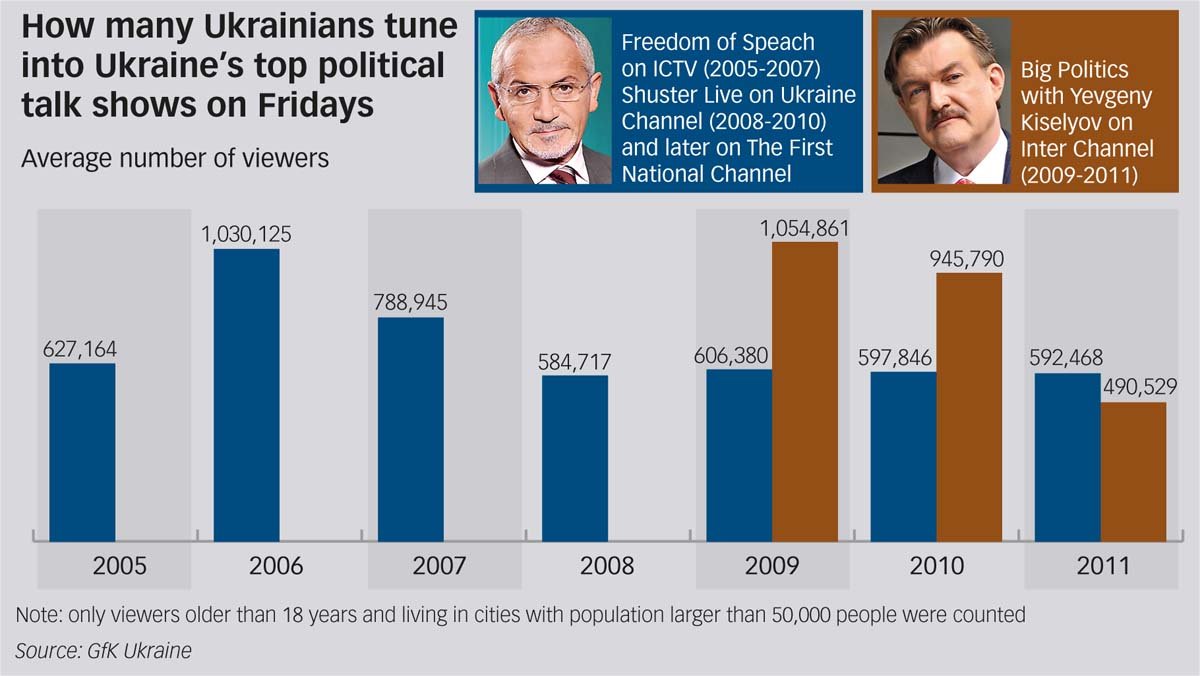

Surveys show that viewers are increasingly tuning out.

Data from GfK Ukraine market research company show that, on average, around 600,000 people watch Shuster Live in its main slot on Fridays, an audience share of 12 percent of adults in large towns and cities.

In 2006, when screened on ICTV, the show regularly drew over 1 million viewers. Kiseliov’s show dropped from around 1 million viewers in 2007 to just under 500,000 this year.

According to the GfK, there is no political talk show in the top 10 programs, whereas two or three regularly made the list just two years ago.

To be sure, interest in politics in Ukraine naturally wanes when no elections are imminent.

“It is a standard thing that interest in politics drops considerably two years after elections or bright political events,” Kiselyov said.

He said that the number of viewers often depends on who is invited as technocratic government members like Prime Minister Mykola Azarov don’t raise as much interest.

Kiselyov also said his show was most popular during the presidential election campaign during winter 2009-2010, when it was screened at 8.30 p.m. It now starts at 10.30 p.m.

He predicted a rise in ratings as next fall’s parliamentary elections approach.

Shuster called statistics showing a drop in ratings “lies” and declined further comment.

Experts and others say there is more to the drop in ratings than just a cyclical pattern.

“I’ve noted that lately the topics of European Union-Ukraine relations were widely discussed in your talk shows on Fridays. I was surprised that the EU’s position in your discussions wasn’t presented by corresponding legitimate EU representatives,” European Union ambassador to Ukraine Jose Manuel Pinto Teixeira wrote to Shuster, after not being invited to give the EU position on one recent show.

On Oct. 28, Kiselyov’s show gave over an hour of airtime to Deputy General Prosecutor Renat Kuzmin, who spent the time throwing accusations at jailed former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, with no one present from the opposition to challenge his claims.

“Big Politics with Yevgeny Kiselyov’ can be called pro-presidential. ‘Shuster Live’ is partially so,” Ligachova said.

While people are turning off political shows, they are switching over to soap operas, according to research by Russian production center WeiT Media.

“Now Ukrainians prefer kind and romantic series, while Russians turn more to detectives,” said Timur Weinstein, a well-known Russian TV producer who runs WeiT Media.

A survey by this media group showed that, on average, people watch political shows as often as children’s programs. This makes them 10 times less popular than entertainment shows, such as X-Factor and Ukraine’s Got Talent, Weinstein said.

According to research by audience measuring company Mediametrie, soap operas and movies draw 53 percent of audiences in Ukraine in comparison to 39 percent worldwide.

But audience interests can change quickly, experts say. Some predict that news and political talk shows will make a comeback given the increased number of protests against the government’s policies.

“We can see multiple protests in Ukraine: pensioners, small business owners, just people,” said Maksym Boroda, an analyst at the International Centre for Policy Studies. “It will result in increased interest in news and political talk-shows. I think we will see some kind of political TV comeback.”

Kyiv Post staff writer Yuliya Raskevich can be reached at raskevich@kyivpost.com.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter