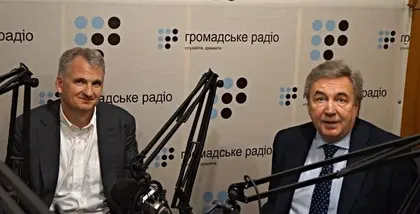

Six years ago, when I was one of the hosts and interviewers for Hromadske Radio’s weekly Ukraine Calling program, I had the privilege of having the distinguished scholar, writer and thinker, Yale history professor, Timothy Snyder on my show. The occasion was the 75th anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacres of Kyiv’s Jews by the Nazis in 1941.

We discussed not only that tragic theme and its significance, but also more broadly about how Ukrainians view their country’s history, how they are perceived by others, and the perspectives for Ukraine’s development. The importance of these issues have been re-emphasized by Russia’s war to destroy Ukraine, its state and self-identification, and by the response of the Ukrainians themselves and the outside world.

So here is an abridged version of our discussion with the emphasis on the main thoughts expressed by Professor Snyder and me that are particularly relevant for today as Ukraine fights for its survival and future.

Nahaylo: What is the broader significance of what occurred at Babyn Yar?

Snyder: Babyn Yar demonstrated how the Holocaust could be carried out. It was at this moment, the summer of 1941, that the Germans realized that the thing Hitler and others called “the final solution” could become the horrible reality that we remember as the Holocaust. This method that was carried out by in Babyn Yar – the cooperation of German institutions, the mass shooting in the open air, the increasing collaboration of local people – this was the method that was applied all over the occupied Soviet Union, not just in Ukraine, but in Belarus, the Baltic States, western Russia, everywhere the Germans went killing (not on this scale – this was the largest), killing of this kind was carried out as the German army moved to the east, and even as they came back to the west as in Kerch, for example, there were further mass killings. In this way more than two million human beings lost their lives, and, in this way, we also learn what human beings are capable of.

Nahaylo: How could it have happened? That, only after a few days after the Germans marched in [to Kyiv] they were able to round up tens of thousands of people and just shoot them?

Snyder: Part of the answer is that it does not actually take much to turn a human being into a killer. Unfortunately, the question is the opposite. How do we preserve the institutions, the ways of life, the laws, the habits that prevent us from doing things like this? But back to your question.

I think most historians would emphasize three factors. The first one is an idea, a big idea, an ideology in which Jews have a specific and central place. In Hitler’s world view Jews are responsible for all evil because it is Jews who prevent Germans from being always victorious, from taking what they want, which is the second idea.

The second idea is Lebensraum: empire, colonies, and the notion that Germans as a superior race deserve to conquer Eastern Europe and, in particular, need to control the fertile soil of Ukraine. Without the idea of racial war in Ukraine, without the quest for Lebensraum, German forces would not have come to Kyiv in the first place. That is another very important component of what happened.

The third idea is lawlessness, statelessness, the separation of Jews and everyone else from the normal pattern of daily life by the alteration, mutilation or even the destruction of the Rule of Law, and the states themselves. We stereotype Germans as being orderly. In fact, the German march into the Eastern Europe through Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and finally the Soviet Union was a constant generation of chaos, of lawlessness, of statelessness, which allowed people to do things they would not have done in other situations.

Nahaylo: How should we remember Babyn Yar today? Is enough being done at this stage to remember it in a dignified way, in a way that has lessons for all of us?

Snyder: I offer what I think, but very modestly and as a proposition. Because the business of memory is a business of national societies, and they have to work things out. As I see it, there are three levels. There is the Holocaust as a general problem, a problem how humans behave. This is a universal meaning. It is relevant for you and me as well as for Ukrainians in Kyiv.

The history of the Holocaust in Belarus, Ukraine, Russia is very much the same. Trying to explain why local people took part in shootings, for example, is just as relevant for Russians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, as it is for Ukrainians. Because that is how the Holocaust happened here.

That said, and this is the third level, we cannot expect that Russians, Ukrainians, and Lithuanians will carry out remembrance together. Remembrance should be done nationally. It seems to me that the history you share might be universal or might be broader than your own nation but how you choose to remember is characteristic of your nation. Or better yet, how you choose to remember is how you choose to build your nation.

It’s very much my sense that if Ukrainians wish to build a political nation with a future, they have to be able to look reflectively upon the past. Not to take responsibility for everything because that would be too much, but to find a way to take responsibility for something. If there is zero responsibility, there is also zero nation.

Nahaylo: At this stage of historic development, at least in Europe, we do not try to build nation states anymore.

Snyder: That is an excellent point. A political nation means an ability to converse within a political society where not everyone has the same cultural origins, maybe not even the same language. Political nation means the ability to converse. And it could arise only through the ability to converse about the past. If we have no ability to get over our own position with the past events, then we have no ability get beyond our political narcissism in the present.

For me, the process of creating a political nation is always a historical process as well. It always involves the ability to be reflective on the people you identify with in the past and to see other points of view in the past. If you cannot do that, if you cannot create a conversation about the past, it is going to be very hard to do it in the present.

Nahaylo: It is obviously a very interesting set of questions that you raise. On one hand Ukrainians need to have an inclusive view of their past and the past of their neighbors who shared the territory, who also suffered on this territory. On the other hand, in a parallel process, as your books indicate, there is a need for the western audience to understand more globally the inter-dependence or interconnectedness of these tragedies and atrocities in terms of what they mean for the human psyche and the human development.

Snyder: Thank you.

Nahaylo: Where do you see today’s Ukraine in the scheme of things? You are a historian of not just the 30s and 40s and these tragic times, but you are also someone who is looking at the positive developments and movements. Where would you place Ukraine in the scheme of things now, before and after the Maidan?

Snyder: The fate of Ukraine was central in the entire history of the 20th century and is also central in the history of 21st, at least in the West. Ukraine was at the center of the rivalry between two different kinds of empires. The national-socialist attempt to conquer Ukraine for their own purposes. But also, the Soviet Union’s attempt to exploit Ukrainian territory to build what Stalin understood as socialism. Ukraine was right in the middle. That is why so many people died in Ukraine. That is why Ukraine was the most dangerous place in the world between 1933 and 1945.

Happily, the nature of political composition today is different from what it was in 1930s-1940s. But nevertheless, Ukraine is still in the center. After the end of the empires we have a new Europe. It is an age of integration where European nation-states rather than seeking to dominate people around the world have built a construction. That construction is called the European Union. It is awkward. It is imperfect. But it is the largest zone of peace and prosperity in the world. But it’s a success, and a non-imperial success.

Ukraine is once again at the edge. If the European model is going to continue, it is because it continues to be attractive. If the Ukrainian state is going to succeed, it is going to succeed because it joins the European Union at some point. In the meantime. the crucial question is, “Can the West help Ukrainians to build a Rule of Law state that functions?” If so, that state will eventually move closer to Europe.

Likewise, as we look even further down the line, Ukraine is basically the only hope for Russia. I mean if one thinks the current Russian model of development is not ideal, there has to be a success in the post-soviet sphere, which shows people from here can also follow the Rule of Law. It is terrifically unfair for Ukrainians that they are in the center of things. But they are. It is just the way it is.

Nahaylo: Finally, thank you on the writing you have done, not simply to set the record straight. I am sure you have made a lot friends, but you also undoubtedly must have made enemies …

Snyder: I’ve made the right kinds of friends. I am very happy I have friends among Ukrainians that came out of age in the 21st century because it is a fantastically interesting generation. I think it will be a transformative generation.

See the original interview in full and podcast here.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter