The “language question” in Ukraine is firmly rooted in centuries of history. The name of the country is a derivation of the old Slavic word for “borderland,” and Ukraine’s struggles are mainly a function of its position between West and East.

Centuries of enforced Russification involved systematic discrimination against Ukraine’s culture and language. The widespread use of the Russian language is the result of official policies during both Tsarist and Soviet times to discriminate against the Ukrainian language. Large-scale Russian immigration to the eastern industrial areas of Ukraine, which resulted in generations of Ukrainians growing up speaking Russian, exacerbated matters, leading to the current conflict.

The UK’s Guardian newspaper published an article in its April 24 edition titled “Russian-speaking Ukrainians want to shed ‘language of the oppressor,’” which focused on a group of women attending a new bi-monthly Ukrainian language club at the Kharkiv Literary Museum.

In many ways the title and tenor of the Guardian’s article reflects the commonly held view that the language used by Ukrainians is and always has been a demonstration of the loyalty, or otherwise, of ordinary Ukrainians to the nation-state. However, Olga Maxwell, a Ukrainian-born Senior Lecturer at the University of Melbourne School of Languages and Linguistics, argues in The Conversation that the reality is somewhat different.

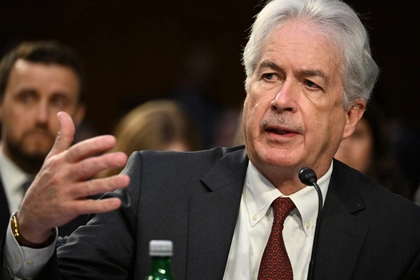

Zelensky Meets CIA Director William Burns in Ukraine

The history of “Russification”

Russian is a widely spoken language as a result of its conquest of other nations over 500 years. The Grand Duchy of Moscow, which was to become the Russian Empire, expanded to the east and north in the 16th century, and by the end of the 19th century had conquered most of Ukraine and Central Asia. World War II allowed the empire’s successor, the Soviet Union, to extend its sphere of influence into Eastern Europe.

Ukraine became a constituent republic of the USSR in 1922. Immediately afterwards, there was a reversal of the Tsarist attempts to submerge Ukraine and its culture under a unified Russian identity. Now, the USSR embarked on a period of “Ukrainization.” As with all things Soviet there was a hidden agenda.

This was part of the wider policy of “indigenization” within all of the republics that made up the USSR. The policy was intended to involve all citizens in all activities of the party apparatus, in order for them to buy into Soviet politics and ideology, public institutions and organizations. In doing so the intent was to establish loyalty to the regime by making the Communist Party “their own,” and to weaken the likelihood that any national liberation movement would threaten the Bolshevik regime.

The honeymoon was short-lived. For most of the 1920s the Ukrainian language and literature flourished; the number of Ukrainian schools and universities grew; Ukrainian was the language of the theatre and government.

All of this changed as Stalin consolidated power. From the late 1920s onwards, those writers, journalists, poets and playwrights who had come to the fore in the brief period of Ukrainization were viciously suppressed. Hundreds of writers were deported, sent to the gulag; some killed themselves, many were shot by the regime. It came to be known as the “Executed Renaissance,” and the killing reached its peak between August 1937 and November 1938, during the period known as the Great Terror.

What does the Russian invasion of Ukraine have to do with language?

Just a few days before the start of his invasion, Vladimir Putin characterized Ukrainian governmental policy towards the Ukrainian language as part of the rationale for his “special military operation,” as it was evidence of the “genocide” against ethnic Russians in the Donbas.

Exactly a week before Putin’s tanks rolled towards Kyiv, Russian diplomats circulated a document to the United Nations Security Council accusing Ukraine of exterminating the civilian population of the self-proclaimed People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk.

The Kremlin had long asserted that Ukraine’s government was persecuting Russian-speaking citizens. It was this, backed by false claims of anti-Russian violence, that was used to justify Putin’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and its invasion of eastern Ukraine. In Putin’s mind, it is his duty to protect Russian populations against a hostile West, and any attempt to move away from Moscow’s influence is an attack on the Russian people as a whole.

Matthew Kupfer and Thomas de Waal, analysts specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region, argue that Moscow has “a long history of use and abuse of genocide rhetoric.”

In Putin’s 2021 essay, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” he tries to depict all things Ukrainian, including the language, as just offshoots of Russian culture; he sees the invasion as an attempt to take back what is rightfully Russia’s and to eliminate Ukrainian identity by any means possible. Alongside wholesale shelling, killing, torture and rape, Russian forces have specifically targeted schools, universities, museums, monuments and cultural centers.

In the occupied territories, Russian-installed authorities have renamed towns and streets, changing road signs into Russian. They have removed Ukrainian books from libraries and schools and thrown them into piles of garbage, changing the Ukrainian-based school curriculum to one that is Russian-based. This is a return to the legacy of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union and the practice of linguistic and cultural imperialism.

Ukrainians are bi-lingual (and many are multi-lingual)

Ukraine is a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual country as, indeed, is Russia. To say that the country is divided only into Russian and Ukrainian speakers, is simply not true. Several languages exist and are used alongside the two main players, including Polish, Hungarian, Greek, Romanian, Crimean Tartar and several others.

The multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic nature of Ukrainian national identity has always had a community component. Contrary to Putin’s false claims, the Russian language is not tied to any regional identity. For a large number of Ukrainians – and not only in the eastern and southern regions – Russian was viewed simply as a means of communication. After all President Volodymyr Zelensky’s first language is Russian; but like many Ukrainians he is bilingual. Indeed, in many parts of the country, people speak a mixture of the two languages called “surzhyk,” a sort of Slavic version of Spanglish or Franglais.

After independence in 1991, Ukrainian was declared to be the official language but, in spite of the efforts of some ultra-nationalists, Russian and other minority languages were granted constitutional protection that allows for their free development and use.

The future of the Ukrainian language

As with every aspect of his attacks on Ukraine the result has been the exact opposite of what Putin intended. Since 2014, the Ukrainian language has become the main cultural expression of Ukrainian identity, more so than it had ever been since Stalin’s attempts to eradicate that identity. Before then the language most Ukrainians spoke was driven by social imperatives; people used the language that made interaction with others easiest and most comfortable.

Following the full-scale invasion of 2022, however, increasing numbers of Ukrainians, whose mother tongue is Russian, are consciously rejecting the language of the “enemy invader.” Rather than a social driver, the choice of language that Ukrainians are making is purely political. The Ukrainian language has become a means of asserting their national identity and, in doing so, showing unity and solidarity. This is yet another battle that Putin is losing.

The views expressed in this opinion article are the author’s and not necessarily those of Kyiv Post.

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter